Tutankhamun, Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen, commonly referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the 18th Dynasty during the New Kingdom of Egyptian history. His father is believed to be the pharaoh Akhenaten, identified as the mummy found in the tomb KV55. His mother is his father's sister, identified through DNA testing as an unknown mummy referred to as "The Younger Lady" who was found in KV35.

Saqqara, also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English, is an Egyptian village in Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara contains numerous pyramids, including the Step pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Tomb, and a number of mastaba tombs. Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km.

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun, a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewellery, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period.

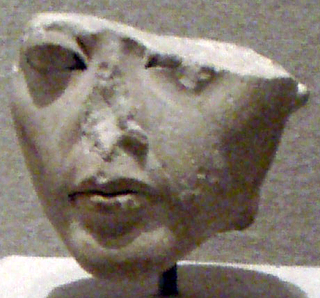

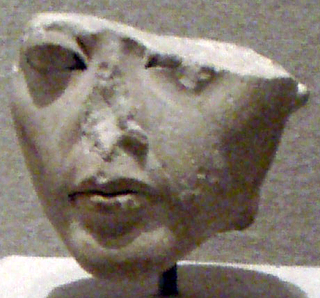

Kiya was one of the wives of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. Little is known about her, and her actions and roles are poorly documented in the historical record, in contrast to those of Akhenaten's ‘Great royal wife’, Nefertiti. Her unusual name suggests that she may originally have been a Mitanni princess. Surviving evidence demonstrates that Kiya was an important figure at Akhenaten's court during the middle years of his reign, when she had a daughter with him. She disappears from history a few years before her royal husband's death. In previous years, she was thought to be mother of Tutankhamun, but recent DNA evidence suggests this is unlikely.

Menpehtyre Ramesses I was the founding pharaoh of ancient Egypt's 19th Dynasty. The dates for his short reign are not completely known but the time-line of late 1292–1290 BC is frequently cited as well as 1295–1294 BC. While Ramesses I was the founder of the 19th Dynasty, his brief reign mainly serves to mark the transition between the reign of Horemheb, who had stabilized Egypt in the late 18th Dynasty, and the rule of the powerful pharaohs of his own dynasty, in particular his son Seti I, and grandson Ramesses II.

Ankhesenamun was a queen who lived during the 18th Dynasty of Egypt as the pharaoh Akhenaten's daughter and subsequently became the Great Royal Wife of pharaoh Tutankhamun. Born Ankhesenpaaten, she was the third of six known daughters of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti. She became the Great Royal Wife of Tutankhamun. The change in her name reflects the changes in ancient Egyptian religion during her lifetime after her father's death. Her youth is well documented in the ancient reliefs and paintings of the reign of her parents. The mummy of Tutankhamun's mother has been identified through DNA analysis as a full sister to his father, the unidentified mummy found in tomb KV55, and as a daughter of his grandfather, Amenhotep III. So far his mother's name is uncertain, but her mummy is known informally to scientists as the Younger Lady.

Deir el-Bahari or Dayr al-Bahri is a complex of mortuary temples and tombs located on the west bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Luxor, Egypt. This is a part of the Theban Necropolis.

The ushabti was a funerary figurine used in ancient Egyptian funerary practices. The Egyptological term is derived from 𓅱𓈙𓃀𓏏𓏭𓀾 wšbtj, which replaced earlier 𓆷𓍯𓃀𓏏𓏭𓀾 šwbtj, perhaps the nisba of 𓈙𓍯𓃀𓆭 šwꜣb "Persea tree".

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculptures, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, architecture, and other art media. It is also very conservative: the art style changed very little over time. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments, giving more insight into the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

Psusennes I was the third pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty who ruled from Tanis between 1047 and 1001 BC. Psusennes is the Greek version of his original name Pasibkhanu or Pasebakhaenniut, which means "The Star Appearing in the City" while his throne name, Akheperre Setepenamun, translates as "Great are the Manifestations of Ra, chosen of Amun." He was the son of Pinedjem I and Henuttawy, Ramesses XI's daughter by Tentamun. He married his sister Mutnedjmet.

Tomb KV15, located in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, was used for the burial of Pharaoh Seti II of the Nineteenth Dynasty. The tomb was dug into the base of a near-vertical cliff face at the head of a wadi running south-west from the main part of the Valley of the Kings. It runs along a northwest-to-southeast axis, comprising a short entry corridor followed by three corridor segments, which terminate in a well room that lacks a well, which was never dug. This then connects with a four-pillared hall and another stretch of corridor that was converted into a burial chamber.

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is a valley in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th century BC, rock-cut tombs were excavated for the pharaohs and powerful nobles of the New Kingdom.

Menhet, Menwi and Merti, also spelled Manhata, Manuwai and Maruta, were three minor foreign-born wives of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Thutmose III who were buried in a lavishly furnished rock-cut tomb in Wady Gabbanat el-Qurud near Luxor, Egypt. They are suggested to be Syrian, as the names all fit into Canaanite name forms, although their ultimate origin is unknown. A West Semitic origin is likely, but both West Semitic and Hurrian derivations have been suggested for Menwi. Each of the wives bear the title of "king's wife", and were likely only minor members of the royal harem. It is not known if the women were related as the faces on the lids of their canopic jars are all different.

Scarabs were popular amulets and impression seals in ancient Egypt. They survive in large numbers and, through their inscriptions and typology, they are an important source of information for archaeologists and historians of the ancient world. They also represent a significant body of ancient art.

Maia was the wet nurse of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun in the 14th century BC. Her rock-cut tomb was discovered in the Saqqara necropolis in 1996.

Tutankhamun's mummy was discovered by English Egyptologist Howard Carter and his team on October 28, 1925 in tomb KV62 of Egypt's Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun was the 13th pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, making his mummy over 3,300 years old. Tutankhamun's mummy is the only royal mummy to have been found entirely undisturbed.

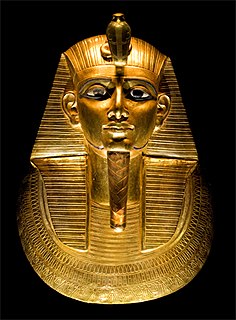

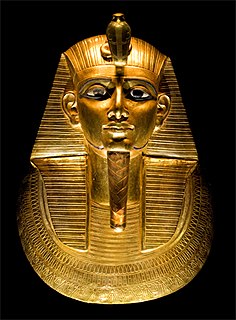

The mask of Tutankhamun is a gold mask of the 18th-dynasty ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun. It was discovered by Howard Carter in 1925 in tomb KV62 in the Valley of the Kings, and is now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The death mask is one of the best-known works of art in the world and a prominent symbol of ancient Egypt.

Mummies 317a and 317b were the infant daughters of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun; their mother is presumed to be his only known wife, Ankhesenamun, who has been tentatively identified as the mummy KV21A. They were buried in their father's tomb, which was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922. Both babies are unnamed, as the coffin inscriptions call them only "the Osiris", so they are known instead by the numbers assigned by Carter during his excavation. They have been examined several times since their discovery, and 317b has been diagnosed with conditions such as Sprengel's deformity and spina bifida, although more recent CT analysis has refuted this. The mummy referred to as 317a is of a girl who was born prematurely at 5–6 months' gestation, and mummy 317b is that of a girl born at or near full term. No cause of death could be determined for either child.

The archaeology of Ancient Egypt is the study of the archaeology of Egypt, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. Egyptian archeology is one of the branches of Egyptology.