Plurality voting refers to electoral systems in which a candidate in an electoral district who polls more than any other is elected. Used for elections of representative bodies, it competes with the proportional representation. In systems based on single-member districts, the plurality system elects just one member per district and is then frequently called a "first-past-the-post" (FPTP), sometimes "single-member [district] plurality" (SMP/SMDP). A system that elects multiple winners elected at once with the plurality rule and where each voter casts multiple X votes in a multi-seat district is referred to as plurality block voting. A semi-proportional system that elects multiple winners elected at once with the plurality rule and where each voter casts just one vote in a multi-seat district is known as single non-transferable voting.

Electoral fraud, sometimes referred to as election manipulation, voter fraud, or vote rigging, involves illegal interference with the process of an election, either by increasing the vote share of a favored candidate, depressing the vote share of rival candidates, or both. It differs from but often goes hand-in-hand with voter suppression. What exactly constitutes electoral fraud varies from country to country, though the goal is often election subversion.

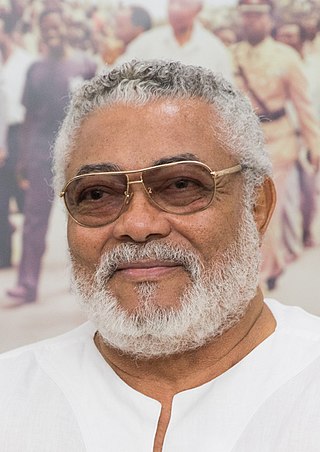

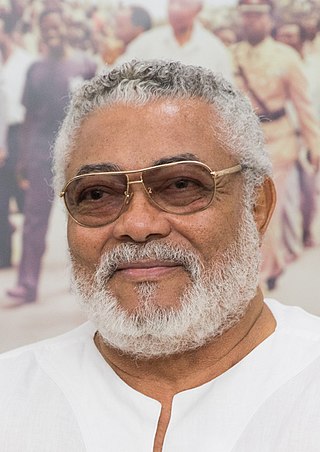

Jerry John Rawlings was a Ghanaian military officer, aviator and politician who led the country for a brief period in 1979, and then from 1981 to 2001. He led a military junta until 1992, and then served two terms as the democratically elected president of Ghana.

The Freedom Front Plus is a right-wing political party in South Africa that was formed in 1994. It is led by Pieter Groenewald.

Regular elections in Croatia are mandated by the Constitution and legislation enacted by Parliament. The presidency, Parliament, county prefects and assemblies, city and town mayors, and city and municipal councils are all elective offices. Since 1990, seven presidential elections have been held. During the same period, ten parliamentary elections were also held. In addition, there were nine nationwide local elections. Croatia has also held three elections to elect members of the European Parliament following its accession to the EU on 1 July 2013.

Particracy, also known as partitocracy, partitocrazia or partocracy, is a form of government in which the political parties are the primary basis of rule rather than citizens or individual politicians.

Every Ghanaian Living Everywhere (EGLE) is an inactive political party in terms of elections in Ghana. It has not contested any elections since the 2004 Ghanaian general election. According to Ghanaian law, political parties must have a presence in all districts in order to remain registered, but due to lax enforcement, EGLE remains registered as a party as of 2019.

An ethnic party is a political party that overtly presents itself as the champion of one ethnic group or sets of ethnic groups. Ethnic parties make such representation central to their voter mobilization strategy. An alternate designation is 'Political parties of minorities', but they should not be mistaken with regionalist or separatist parties, whose purpose is territorial autonomy.

Latino Americans have received a growing share of the national vote in the United States due to their increasing population. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, 62.1 million Latinos live in the United States, representing 18.9% of the total U.S. population. This is a 23% increase since 2010. This racial/ethnic group is the second largest after non-Hispanic whites in the U.S. In 2020, the states with the highest Hispanic or Latino populations were; Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and Texas. According to the Brookings Institution, Latinos will become the nations largest minority by 2045 and the deciding population in future elections. With the help of laws and court case wins, Latinos have been able to receive the help needed to participate in American Politics. According to data provided by The Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS), 72% of Latinos believe that it is very/somewhat important to get their voice heard by voting. They have traditionally been a key Democratic Party constituency, but more recently have begun to split between the Democratic and Republican Party. Since the Latino population is large and diverse, a lot of political differences exist between gender, national origin, and generational groups.

General elections were held in Ghana on 7 December 2008. Since no candidate received more than 50% of the votes, a run-off election was held on 28 December 2008 between the two candidates who received the most votes, Nana Akufo-Addo of the governing New Patriotic Party and John Atta Mills of the opposition National Democratic Congress. Mills was certified as the victor by a margin of less than one percent, winning the presidency on his third attempt. It is to date the closest election in Ghanaian history.

The historical trends in voter turnout in the United States presidential elections have been determined by the gradual expansion of voting rights from the initial restriction to white male property owners aged 21 or older in the early years of the country's independence to all citizens aged 18 or older in the mid-20th century. Voter turnout in United States presidential elections has historically been higher than the turnout for midterm elections.

Clientelism or client politics is the exchange of goods and services for political support, often involving an implicit or explicit quid-pro-quo. It is closely related to patronage politics and vote buying.

General elections were held in Ghana on Friday 7 December 2012 to elect a president and members of Parliament in 275 electoral constituencies. Owing to the breakdown of some biometric verification machines, some voters could not vote, and voting was extended to Saturday 8 December 2012. A run-off was scheduled for 28 December 2012 if no presidential candidate received an absolute majority of 50% plus one vote. Competing for presidency were incumbent president John Dramani Mahama of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), his main challenger Nana Akufo-Addo of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and six other candidates.

Vote buying occurs when a political party or candidate distributes money or resources to a voter in an upcoming election with the expectation that the voter votes for the actor handing out monetary rewards. Vote buying can take various forms such as a monetary exchange, as well as an exchange for necessary goods or services. This practice is often used to incentivise or persuade voters to turn out to elections and vote in a particular way. Although this practice is illegal in many countries such as the United States, Argentina, Mexico, Kenya, Brazil and Nigeria, its prevalence remains worldwide.

The Latino vote or refers to the voting trends during elections in the United States by eligible voters of Latino background. This phrase is usually mentioned by the media as a way to label voters of this ethnicity, and to opine that this demographic group could potentially tilt the outcome of an election, and how candidates have developed messaging strategies to this ethnic group.

General elections were held in Ghana on 7 December 2016 to elect a President and Members of Parliament. They had originally been scheduled for 7 November 2016, but the date was later rejected by Parliament. Former foreign minister Nana Akufo-Addo of the opposition New Patriotic Party was elected President on his third attempt, defeating incumbent President John Mahama of the National Democratic Congress.

General elections were held in Ghana on 7 December 2020. Incumbent President Nana Akufo-Addo of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) was re-elected in the first round after securing a majority of the votes. Former President John Dramani Mahama announced that he would contest the results. At the Supreme Court, a petition challenging the result was filed on 30 December, and unanimously dismissed on 4 March 2021 for lack of merit.

Kofi Koranteng is a Ghanaian activist and politician who used to be the chief executive officer of the Progressive Alliance Movement. He has been a key advocate for the rights of Ghanaians living abroad to be given the chance to vote and be represented in that manner through campaigning for the Representation of the Peoples’ Amendment Act (ROPAA) to be passed. In the run off to the election in December 2019, he declared his intention to stand for the 2020 Ghana elections as an independent candidate.