The United States Shipping Board (USSB) was established as an emergency agency by the 1916 Shipping Act, on September 7, 1916. The United States Shipping Board's task was to increase the number of US ships supporting the World War I efforts. The program ended on March 2, 1934.

SS Cotopaxi was an Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) Design 1060 bulk carrier built for the United States Shipping Board (USSB) under the World War I emergency shipbuilding program. The ship, launched 15 November 1918, was named after the Cotopaxi stratovolcano of Ecuador. The ship arrived in Boston, 22 December 1918, to begin operations for the USSB, through 23 December 1919, when Cotopaxi was delivered to the Clinchfield Navigation Company under terms of sale.

Hog Islanders is the slang for ships built to Emergency Fleet Corporation designs number 1022 and 1024. These vessels were cargo and troop transport ships, respectively, built under government direction and subsidy to address a shortage of ships in the United States Merchant Marine during World War I. American International Shipbuilding, subsidized by the United States Shipping Board, built an emergency shipyard on Hog Island at the site of the present-day Philadelphia International Airport.

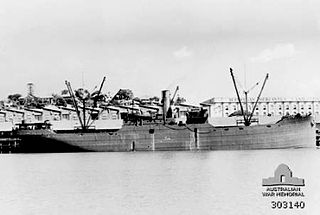

West Compo was a steam cargo ship built in 1918–1919 by Northwest Steel Company of Portland for the United States Shipping Board as part of the wartime shipbuilding program of the Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) to restore the nation's Merchant Marine. The vessel was commissioned into the Naval Overseas Transportation Service (NOTS) of the United States Navy in January 1919 and after only one overseas trip was decommissioned four months later and returned to the USSB. Afterwards the vessel was largely employed on the Atlantic Coast of the United States to France route until mid-1921 when she was laid up and eventually broken up for scrap in 1936.

Cotati was a steam cargo ship built in 1918–1919 by Moore Shipbuilding and Drydock Company of Oakland for the United States Shipping Board (USSB) as part of the wartime shipbuilding program of the Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) to restore the nation's Merchant Marine. The vessel was briefly used for the first two years of her career to transport frozen meat between North and South America and Europe. The ship was subsequently laid up at the end of 1921 and remained part of the Reserve Fleet through the end of 1940. In January 1941 she was sold together with two other vessels to the New Zealand Shipping Co. and subsequently in 1942 was transferred to the Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) and renamed Empire Avocet. The ship was torpedoed and sunk by German submarine U-125 on 30 September 1942 on one of her regular wartime trips.

The Merchant Shipbuilding Corporation was an American corporation established in 1917 by railroad heir W. Averell Harriman to build merchant ships for the Allied war effort in World War I. The MSC operated two shipyards: the former shipyard of John Roach & Sons at Chester, Pennsylvania, and a second, newly established emergency yard at Bristol, Pennsylvania, operated by the MSC on behalf of the U.S. Shipping Board's Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC).

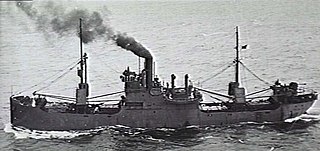

SS West Loquassuck was a steel–hulled cargo ship built for the United States Shipping Board's Emergency Fleet Corporation in World War I. After completion on 15 October 1918, the ship was immediately commissioned into the U.S. Navy as USS West Loquassuck (ID-3638), just weeks before the end of the war.

The Skinner & Eddy Corporation, commonly known as Skinner & Eddy, was a Seattle, Washington-based shipbuilding corporation that existed from 1916 to 1923. The yard is notable for completing more ships for the United States war effort during World War I than any other West Coast shipyard, and also for breaking world production speed records for individual ship construction.

The Design 1023 ship was a steel-hulled cargo ship design approved for mass production by the United States Shipping Board's (USSB) Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) in World War I. Like many of the early designs approved by the EFC, the Design 1023 did not originate with the EFC itself but was based on an existing cargo ship designed by Theodore E. Ferris for the United States Shipping Board (USSB). The ships, to be built by the Submarine Boat Corporation of Newark, New Jersey, were the first to be constructed under a standardized production system worked out by Ferris and approved by the USSB.

Suremico was a Design 1023 cargo ship built for the United States Shipping Board (USSB) immediately after World War I. She was later named the Nisqually and converted into a barge and later a scow. She was bombed and sunk during the Battle of Wake Island.

The Design 1014 ship was a steel-hulled cargo ship design approved for production by the United States Shipping Board's Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFT) in World War I. They were referred to as the "Cascade"-type. They were all built by Todd Drydock and Construction Company, at their Tacoma, Washington shipyard. 20 ships were completed for the USSB in 1919 and 1920; and additional 2 were completed in 1920 for private companies. 12 ships were cancelled.

SS Lake Elsmere was an Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) Design 1074 cargo ship built for the United States Shipping Board (USSB) during the massive shipbuilding effort of World War I.

SSCassimir was a Design 1022 cargo ship built for the United States Shipping Board immediately after World War I.

SSCarrabulle was a Design 1022 cargo ship built for the United States Shipping Board immediately after World War I.

The Design 1041 ship was a steel-hulled tanker ship design approved for production by the United States Shipping Board's Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFT) in World War I. A total of 13 ships were ordered and completed for the USSB from 1919 to 1920. The ships were constructed at the Oakland, California shipyard of Moore Shipbuilding Company. An additional 5 ships were completed separately by the shipyard.

The Design 1065 ship was a wooden-hulled cargo ship design approved for production by the United States Shipping Board's Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFT) in World War I. A total of 7 ships were ordered and completed for the USSB from 1918 to 1919. The ships were constructed at the Bellingham, Washington shipyard of Pacific American Fisheries. The USSB originally wanted Pacific American Fisheries to follow its standard "Ferris-type" design used by other shipyards but PAF was successful in convincing them to use their own design which they felt was more seaworthy. The cost was $50,000 per ship.

USAT Arcata, was built in 1919 as the SS Glymont for the United States Shipping Board as a merchant ship by the Albina Engine & Machine Works in Portland, Oregon. The 2,722-ton cargo ship Glymont was operated by the Matson Navigation till 1923 in post World War I work. In 1923 she was sold to Cook C. W. of San Francisco. In 1925 she was sold to Nelson Charles Company of San Francisco. In 1937 she was sold to Hammond Lumber Company of Fairhaven, California. For World War II, in 1941, she was converted to a US Army Troopship, USAT Arcata. She took supplies and troops to Guam. On July 14, 1942, she was attacked by Japanese submarine I-7 and sank. She was operating as a coastal resupply in the Gulf of Alaska, south of the Aleutian Islands at, approximately 165 nautical miles southeast of Sand Point, when she sank. She was returning after taking supplies to Army troops fighting in the Aleutian Islands campaign.

The Design 1005 ship was a wood-hulled cargo ship design approved for production by the United States Shipping Board's Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFT) in World War I. The ships were referred to as the "Grays Harbor"-type as all were built by the Grays Harbor Motorship Company in Aberdeen, Washington or the "Ward"-type after their designer M. R. Ward. The first ship of the class, the SS Wishkah, was listed at 2,924 gross tons with dimensions of 272.1 x 48.4 x 25.7, 1400 indicated horsepower, and carried a crew of 47. The class does not include the four Design 1116 cargo ships also designed by Ward and completed at the shipyard as they were a modified design at 3,132 gross tons and 5,000 tons deadweight. All ships were completed in 1918 or 1919.

The Design 1006 ship was a wood-hulled cargo ship design approved for production by the United States Shipping Board's Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFT) in World War I. They were referred to as the "Daugherty"-type after A. A. Daugherty, the president of the National Shipbuilding Company. The USSB ordered a total of 40 hulls from three shipyards: National Shipbuilding Company of Orange, Texas shipyard ; Union Bridge & Construction Company of Morgan City, Louisiana shipyard ; and Dirks Blodgett Shipbuilding Company of Pascagoula, Mississippi. The design was altered by National Shipbuilding increasing the deadweight to 5,000 tons. Only 12 were completed for the USSB while two were built as tankers in 1920 for the National Oil Transportation Company of Port Arthur, Texas and one as a barge.