Related Research Articles

Meharry Medical College is a private historically black medical school affiliated with the United Methodist Church and located in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1876 as the Medical Department of Central Tennessee College, it was the first medical school for African Americans in the South. This region had the highest proportion of this ethnicity, but they were excluded from many public and private segregated institutions of higher education, particularly after the end of Reconstruction.

Walden University was a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1865 by missionaries from the Northern United States on behalf of the Methodist Church to serve freedmen. Known as Central Tennessee College from 1865 to 1900, Walden University provided education and professional training to African Americans until 1925.

The Erlanger Health System, incorporated as the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Hospital Authority, a non-profit, public benefit corporation registered in the State of Tennessee, is a system of hospitals, physicians, and medical services based in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Erlanger's main location, Erlanger Baroness Hospital, is a tertiary referral hospital and Level I Trauma Center serving a 50,000 sq mi (130,000 km2) region of East Tennessee, North Georgia, North Alabama, and western North Carolina. The system provides critical care services to patients within a 150 mi (240 km) radius through six Life Force air ambulance helicopters, which are equipped to perform in-flight surgical procedures and transfusions.

Dorothy Lavinia Brown, also known as "Dr. D.", was an African-American surgeon, legislator, and teacher. She was the first female surgeon of African-American ancestry from the Southeastern United States. She was also the first African American female to serve in the Tennessee General Assembly as she was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. While serving in the House of Representatives, Brown fought for women's rights and for the rights of people of color.

Matthew Walker Sr. was an American physician and surgeon. He was one of the first African Americans to become a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons. He was one of the most prominent Black doctors in the 20th century in the United States.

John Angelo Lester was an American educator, physician and administrator in Nashville, Tennessee between 1895 and 1934. He was a professor of physiology at Meharry Medical College and was named Professor Emeritus in 1930. Lester served as an executive officer in the National Medical Association and various state and regional medical associations throughout Tennessee, a mecca for Negro physicians since Reconstruction.

Georgia Rooks Dwelle (1884–1977) was a physician in Atlanta, Georgia who specialized in obstetrics and pediatrics. When Dwelle was licensed as a physician in 1904, she was one of only three African American women physicians in the state of Georgia. Dwelle began to practice medicine at a time when Jim Crow laws and social customs in Georgia required racial segregation in medical schools, health care facilities, and medical societies. To counter the lack of medical care for African-Americans in Atlanta, Dwelle opened the Dwelle Infirmary which was the first successful private general hospital for African Americans in Atlanta, and the first obstetrical hospital for African American women in Atlanta.

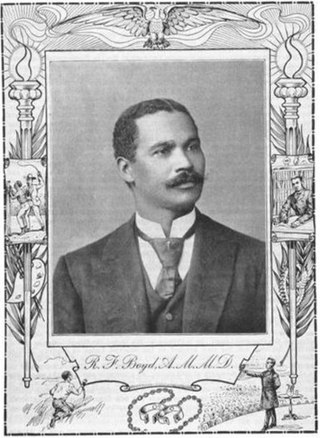

Robert Fulton Boyd was a physician, dentist, pharmacist, professor, teacher, politician, and most notably, the co-founder and first president of the National Medical Association. He was a man of many talents, infinite curiosity and compassion who multifariously impacted the lives of the communities he was a part of, all while remaining humble. He fought political oppression by involving himself in local politics, and racial segregation in healthcare, faced by the black community in the 19th century, leaving a permanent mark on the American medical community. Although his life was cut short, Boyd nonetheless enlightened the people around him, inspiring education and healthcare.

Clara Arena Brawner was the only African-American woman physician in Memphis, Tennessee, in the mid-1950s.

Natalia Tanner was an American physician. She was the first female African-American fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She is known for her activism promoting women and people of color in medicine and fighting health inequality in the United States.

Mary Bell was born on July 28, 1840 in Hillsboro, Ohio. She was a nurse and hospital matron in the Civil War.

Eugene Heriot Dibble Jr. (1893–1968) was an American physician and head of the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He played an important role in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which was a clinical study conducted on syphilis in African American males from 1932 to 1972.

Dr. Winston Clifton Hackett (1881–1949) was the first African American physician in Arizona. He was the founder of the Booker T. Washington Memorial Hospital, the first hospital in Phoenix which served the African American community.

Hulda Margaret Lyttle Frazier was an American nurse educator and hospital administrator who spent most of her career in Nashville, Tennessee at Meharry Medical College School of Nursing and affiliated Hubbard Hospital. Lyttle advocated for the modernization and professionalization of African American nurses' training programs, and improved practice standards in hospitals that served African Americans.

David Bernard Todd Jr. was an American surgeon. He was a professor of Surgery at Meharry Medical College, and the first African-American cardiovascular surgeon in Nashville, Tennessee. He is the namesake of Dr DB Todd Jr. Boulevard in North Nashville.

The Millie E. Hale Hospital was a hospital in Nashville, Tennessee that served African-American patients. It was the first hospital to serve black patients year-round. The hospital was opened by a husband and wife team, Dr. John Henry Hale and Millie E. Hale in July 1916. The couple first turned their home into a hospital that would grow to house 75 patients by 1923. In addition to the hospital, there was a community center and ladies' auxiliary that provided health services and also recreational and charity work to the black community. The hospital also provided parks for children who had no park to use in the Jim Crow era. In 1938, the hospital closed, but some social services continued afterwards.

Ursula Joyce Yerwood was the first female African American physician in Fairfield County, Connecticut, and founder of the Yerwood Center, the first community center for African Americans in Stamford, Connecticut.

John Henry Hale was a prominent surgeon, professor, and philanthropist who played a prominent role in establishing the black medical community. Hailed as the "dean of American Negro surgeons," Hale conducted over 30,000 surgeries, mainly at Meharry Medical College and Millie E. Hale Hospital. He practiced medicine and taught at Meharry for 29 years, mentoring a plethora of black surgeons.

Millie Essie Gibson Hale was an American nurse and hospital administrator. In 1916 she founded Millie E. Hale Hospital with her husband, John Henry Hale, M.D., in Nashville, Tennessee.

References

- ↑ Sawyer, Susan (2000). More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Tennessee Women (First ed.). Helena, Montana: Falcon Publishing. pp. 91–96. ISBN 9781560449010 . Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- 1 2 Wynn, Linda (1996). Profiles of African Americans in Tennessee. Nashville, TN: Annual Local Conference on Afro-American Culture and History. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ Hubbard, Rita L. (2007). African Americans of Chattanooga: A History of Unsung Heroes (1 ed.). Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 93–98. ISBN 9781596293151 . Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ Greene, Vivian P. "Walden Hospital". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Old Walden Hospital Getting New Life". The Chattanoogan. The Chattanoogan. 9 August 2002. Retrieved 29 October 2014.