The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an independent executive agency of the United States federal government tasked with environmental protection matters. President Richard Nixon proposed the establishment of EPA on July 9, 1970; it began operation on December 2, 1970, after Nixon signed an executive order. The order establishing the EPA was ratified by committee hearings in the House and Senate.

Carol Martha Browner is an American lawyer, environmentalist, and businesswoman, who served as director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy in the Obama administration from 2009 to 2011. Browner previously served as Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) during the Clinton administration from 1993 to 2001. She currently works as a Senior Counselor at Albright Stonebridge Group, a global business strategy firm.

Stephen Lee Johnson is an American politician who served as the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under President George W. Bush during the second term of his administration. He has received the Presidential Rank Award, the highest award that can be given to a civilian federal employee.

Lisa Perez Jackson is an American chemical engineer who served as the administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from 2009 to 2013. She was the first African American to hold that position.

Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency, 549 U.S. 497 (2007), is a 5–4 U.S. Supreme Court case in which Massachusetts, along with eleven other states and several cities of the United States, represented by James Milkey, brought suit against the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) represented by Gregory G. Garre to force the federal agency to regulate the emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) that pollute the environment and contribute to climate change.

The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, originally named the Clean Energy Act of 2007, is an Act of Congress concerning the energy policy of the United States. As part of the Democratic Party's 100-Hour Plan during the 110th Congress, it was introduced in the United States House of Representatives by Representative Nick Rahall of West Virginia, along with 198 cosponsors. Even though Rahall was 1 of only 4 Democrats to oppose the final bill, it passed in the House without amendment in January 2007. When the Act was introduced in the Senate in June 2007, it was combined with Senate Bill S. 1419: Renewable Fuels, Consumer Protection, and Energy Efficiency Act of 2007. This amended version passed the Senate on June 21, 2007. After further amendments and negotiation between the House and Senate, a revised bill passed both houses on December 18, 2007 and President Bush, a Republican, signed it into law on December 19, 2007, in response to his "Twenty in Ten" challenge to reduce gasoline consumption by 20% in 10 years.

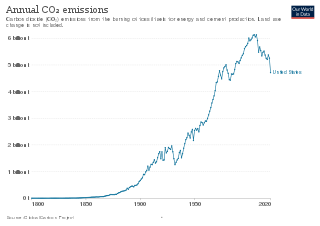

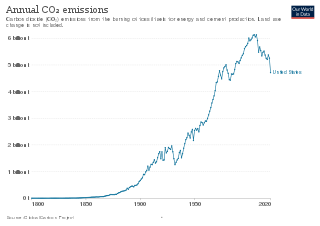

The United States produced 5.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020, the second largest in the world after greenhouse gas emissions by China and among the countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions per person. In 2019 China is estimated to have emitted 27% of world GHG, followed by the United States with 11%, then India with 6.6%. In total the United States has emitted a quarter of world GHG, more than any other country. Annual emissions are over 15 tons per person and, amongst the top eight emitters, is the highest country by greenhouse gas emissions per person. However, the IEA estimates that the richest decile in the US emits over 55 tonnes of CO2 per capita each year. Because coal-fired power stations are gradually shutting down, in the 2010s emissions from electricity generation fell to second place behind transportation which is now the largest single source. In 2020, 27% of the GHG emissions of the United States were from transportation, 25% from electricity, 24% from industry, 13% from commercial and residential buildings and 11% from agriculture. In 2021, the electric power sector was the second largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 25% of the U.S. total. These greenhouse gas emissions are contributing to climate change in the United States, as well as worldwide.

United States vehicle emission standards are set through a combination of legislative mandates enacted by Congress through Clean Air Act (CAA) amendments from 1970 onwards, and executive regulations managed nationally by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and more recently along with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). These standard cover common motor vehicle air pollution, including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate emissions, and newer versions have incorporated fuel economy standards.

The environmental policy of the United States is a federal governmental action to regulate activities that have an environmental impact in the United States. The goal of environmental policy is to protect the environment for future generations while interfering as little as possible with the efficiency of commerce or the liberty of the people and to limit inequity in who is burdened with environmental costs. As his first official act bringing in the 1970s, President Richard Nixon signed the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) into law on New Years Day, 1970. Also in the same year, America began celebrating Earth Day, which has been called "the big bang of U.S. environmental politics, launching the country on a sweeping social learning curve about ecological management never before experienced or attempted in any other nation." NEPA established a comprehensive US national environmental policy and created the requirement to prepare an environmental impact statement for “major federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the environment.” Author and consultant Charles H. Eccleston has called NEPA, the world's “environmental Magna Carta”.

New Energy for America was a plan led by Barack Obama and Joe Biden beginning in 2008 to invest in renewable energy sources, reduce reliance on foreign oil, address global warming issues, and create jobs for Americans. The main objective for the New Energy for America plan was to implement clean energy sources in the United States in order to switch from nonrenewable resources to renewable resources. The plan led by the Obama Administration aimed to implement short-term solutions to provide immediate relief from pain at the pump, and mid- to- long-term solutions to provide a New Energy for America plan. The goals of the clean energy plan hoped to: invest in renewable technologies that will boost domestic manufacturing and increase homegrown energy, invest in training for workers of clean technologies, strengthen the middle class, and help the economy.

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is the United States' primary federal air quality law, intended to reduce and control air pollution nationwide. Initially enacted in 1963 and amended many times since, it is one of the United States' first and most influential modern environmental laws.

To protect the environment from the adverse effects of pollution, many nations worldwide have enacted legislation to regulate various types of pollution as well as to mitigate the adverse effects of pollution. At the local level, regulation usually is supervised by environmental agencies or the broader public health system. Different jurisdictions often have different levels regulation and policy choices about pollution. Historically, polluters will lobby governments in less economically developed areas or countries to maintain lax regulation in order to protect industrialisation at the cost of human and environmental health.

The American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (ACES) was an energy bill in the 111th United States Congress that would have established a variant of an emissions trading plan similar to the European Union Emission Trading Scheme. The bill was approved by the House of Representatives on June 26, 2009, by a vote of 219–212. With no prospect of overcoming a threatened Republican filibuster, the bill was never brought to the floor of the Senate for discussion or a vote. The House passage of the bill was the "first time either house of Congress had approved a bill meant to curb the heat-trapping gases scientists have linked to climate change."

The climate change policy of the United States has major impacts on global climate change and global climate change mitigation. This is because the United States is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gasses in the world after China, and is among the countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions per person in the world. In total, the United States has emitted over 400 billion metric tons of greenhouse gasses, more than any country in the world.

American Electric Power Company v. Connecticut, 564 U.S. 410 (2011), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court, in an 8–0 decision, held that corporations cannot be sued for greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) under federal common law, primarily because the Clean Air Act (CAA) delegates the management of carbon dioxide and other GHG emissions to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Brought to court in July 2004 in the Southern District of New York, this was the first global warming case based on a public nuisance claim.

The, United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began regulating greenhouse gases (GHGs) under the Clean Air Act from mobile and stationary sources of air pollution for the first time on January 2, 2011. Standards for mobile sources have been established pursuant to Section 202 of the CAA, and GHGs from stationary sources are currently controlled under the authority of Part C of Title I of the Act. The basis for regulations was upheld in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in June 2012.

The Electricity Security and Affordability Act is a bill that would repeal a pending rule published by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on January 8, 2014. The proposed rule would establish uniform national limits on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from new electricity-generating facilities that use coal or natural gas. The rule also sets new standards of performance for those power plants, including the requirement to install carbon capture and sequestration technology.

The Clean Power Plan was an Obama administration policy aimed at combating anthropogenic climate change that was first proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in June 2014. The final version of the plan was unveiled by President Obama on August 3, 2015. Each state was assigned an individual goal for reducing carbon emissions, which could be accomplished how they saw fit, but with the possibility of the EPA stepping in if the state refused to submit a plan. If every state met its target, the plan was projected to reduce carbon emissions from electricity generation 32% by 2030, relative to 2005 levels, as well as achieving various health benefits due to reduced air pollution.

Andrew R. Wheeler is an American attorney who served as the 15th administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from 2019 to 2021. He served as the deputy administrator from April to July 2018, and served as the acting administrator from July 2018 to February 2019. He has been a senior advisor to Governor of Virginia Glenn Youngkin since March 2022. He previously worked in the law firm Faegre Baker Daniels, representing coal magnate Robert E. Murray and lobbying against the Obama Administration's environmental regulations. Wheeler served as chief counsel to the United States Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works and to the chairman U.S. senator James Inhofe, prominent for his rejection of climate change. Wheeler is a critic of limits on greenhouse gas emissions and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, 597 U.S. ___ (2022), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court relating to the Clean Air Act, and the extent to which the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) can regulate carbon dioxide emissions related to climate change.