Related Research Articles

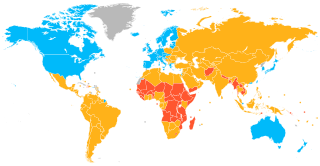

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreement on which countries fit this category. The terms low and middle-income country (LMIC) and newly emerging economy (NEE) are often used interchangeably but refers only to the economy of the countries. The World Bank classifies the world's economies into four groups, based on gross national income per capita: high, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low income countries. Least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing states are all sub-groupings of developing countries. Countries on the other end of the spectrum are usually referred to as high-income countries or developed countries.

In the United Nations, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were eight international development goals for the year 2015 created following the Millennium Summit, following the adoption of the United Nations Millennium Declaration. These were based on the OECD DAC International Development Goals agreed by Development Ministers in the "Shaping the 21st Century Strategy". The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) succeeded the MDGs in 2016.

Feminization of poverty refers to a trend of increasing inequality in living standards between men and women due to the widening gender gap in poverty. This phenomenon largely links to how women and children are disproportionately represented within the lower socioeconomic status community in comparison to men within the same socioeconomic status. Causes of the feminization of poverty include the structure of family and household, employment, sexual violence, education, climate change, "femonomics" and health. The traditional stereotypes of women remain embedded in many cultures restricting income opportunities and community involvement for many women. Matched with a low foundation income, this can manifest to a cycle of poverty and thus an inter-generational issue.

African environmental issues are caused by human impacts on the natural environment and affect humans and nearly all forms of life. Issues include deforestation, soil degradation, air pollution, water pollution, garbage pollution, climate change and water scarcity. These issues result in environmental conflict and are connected to broader social struggles for democracy and sovereignty.

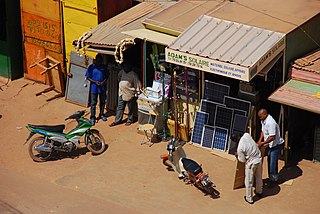

In developing countries and some areas of more developed countries, energy poverty is lack of access to modern energy services in the home. Today, 759 million people lack access to consistent electricity and 2.6 billion people use dangerous and inefficient cooking systems. Their well-being is negatively affected by very low consumption of energy, use of dirty or polluting fuels, and excessive time spent collecting fuel to meet basic needs.

Household air pollution (HAP) is a significant form of indoor air pollution mostly relating to cooking and heating methods used in developing countries. Since much of the cooking is carried out with biomass fuel, in the form of wood, charcoal, dung, and crop residue, in indoor environments that lack proper ventilation, millions of people, primarily women and children face serious health risks. In total, about three billion people in developing countries are affected by this problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that cooking-related pollution causes 3.8 million annual deaths. The Global Burden of Disease study estimated the number of deaths in 2017 at 1.6 million. The problem is closely related to energy poverty and cooking.

Gender inequality is the social phenomenon in which people are not treated equally on the basis of gender. This inequality can be caused by gender discrimination or sexism. The treatment may arise from distinctions regarding biology, psychology, or cultural norms prevalent in the society. Some of these distinctions are empirically grounded, while others appear to be social constructs. While current policies around the world cause inequality among individuals, it is women who are most affected. Gender inequality weakens women in many areas such as health, education, and business life. Studies show the different experiences of genders across many domains including education, life expectancy, personality, interests, family life, careers, and political affiliation. Gender inequality is experienced differently across different cultures and also affects non-binary people.

Women in Uganda have substantial economic and social responsibilities throughout Uganda's many traditional societies. Ugandan women come from a range of economic and educational backgrounds. Despite economic and social progress throughout the country, domestic violence and sexual assault remain prevalent issues in Uganda. Illiteracy is directly correlated to increased level of domestic violence. This is mainly because household members can not make proper decisions that directly affect their future plans. Government reports suggest rising levels of domestic violence toward women that are directly attributable to poverty.

Renewable energy in developing countries is an increasingly used alternative to fossil fuel energy, as these countries scale up their energy supplies and address energy poverty. Renewable energy technology was once seen as unaffordable for developing countries. However, since 2015, investment in non-hydro renewable energy has been higher in developing countries than in developed countries, and comprised 54% of global renewable energy investment in 2019. The International Energy Agency forecasts that renewable energy will provide the majority of energy supply growth through 2030 in Africa and Central and South America, and 42% of supply growth in China.

Rural poverty refers to situations where people living in non-urban regions are in a state or condition of lacking the financial resources and essentials for living. It takes account of factors of rural society, rural economy, and political systems that give rise to the marginalization and economic disadvantage found there. Rural areas, because of their small, spread-out populations, typically have less well maintained infrastructure and a harder time accessing markets, which tend to be concentrated in population centers.

Project Gaia is a U.S.-based non-governmental, non-profit organization engaged in developing alcohol-based fuel markets for household use in Ethiopia and other developing countries. The organization identifies alcohol fuels as a potential alternative to traditional cooking methods, which they suggest may contribute to fuel shortages, environmental issues, and public health concerns in these regions. Focusing on impoverished and marginalized communities, Project Gaia is active in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Brazil, Haiti, and Madagascar. The organization is also planning to expand its projects to additional countries.

Energy use and development in Africa varies widely across the continent, with some African countries exporting energy to neighbors or the global market, while others lack even basic infrastructures or systems to acquire energy. The World Bank has declared 32 of the 48 nations on the continent to be in an energy crisis. Energy development has not kept pace with rising demand in developing regions, placing a large strain on the continent's existing resources over the first decade of the new century. From 2001 to 2005, GDP for over half of the countries in Sub Saharan Africa rose by over 4.5% annually, while generation capacity grew at a rate of 1.2%.

In feminist economics, the feminization of agriculture refers to the measurable increase of women's participation in the agricultural sector, particularly in the developing world. The phenomenon started during the 1960s with increasing shares over time. In the 1990s, during liberalization, the phenomenon became more pronounced and negative effects appeared in the rural female population. Afterwards, agricultural markets became gendered institutions, affecting men and women differently. In 2009 World Bank, FAO & IFAD found that over 80 per cent of rural smallholder farmers worldwide were women, this was caused by men migrating to find work in other sectors. Out of all the women in the labor sector, the UN found 45-80% of them to be working in agriculture

Gender inequality both leads to and is a result of food insecurity. According to estimates, women and girls make up 60% of the world's chronically hungry and little progress has been made in ensuring the equal right to food for women enshrined in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Women face discrimination both in education and employment opportunities and within the household, where their bargaining power is lower. On the other hand, gender equality is described as instrumental to ending malnutrition and hunger. Women tend to be responsible for food preparation and childcare within the family and are more likely to be spent their income on food and their children's needs. The gendered aspects of food security are visible along the four pillars of food security: availability, access, utilization and stability, as defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization.

The extent of gender inequalities varies throughout Liberia in regard to status, region, rural/urban areas, and traditional cultures. In general, women in Liberia have less access to education, health care, property, and justice when compared to men. Liberia suffered two devastating civil wars from 1989–1996 and 1999–2003. The wars left Liberia nearly destroyed with minimal infrastructure and thousands dead. Liberia has a Human Development Report ranking of 174 out of 187 and a Gender Inequality Index rank of 154 out of 159.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity." Identified by the 2012 World Development Report as one of two key human capital endowments, health can influence an individual's ability to reach his or her full potential in society. Yet while gender equality has made the most progress in areas such as education and labor force participation, health inequality between men and women continues to harm many societies to this day.

Climate change affects men and women differently. Climate change and gender examines how men and women access and use resources that are impacted by climate change and how they experience the resulting impacts. It examines how gender roles and cultural norms influence the ability of men and women to respond to climate change, and how women's and men's roles can be better integrated into climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies. It also considers how climate change intersects with other gender-related challenges, such as poverty, access to resources, and unequal power dynamics. Ultimately, the goal of this research is to ensure that climate change policies and initiatives are equitable, and that both women and men benefit from them. Climate change increases gender inequality, reduces women's ability to be financially independent, and has an overall negative impact on the social and political rights of women, especially in economies that are heavily based on agriculture. In many cases, gender inequality means that women are more vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change. This is due to gender roles, particularly in the developing world, which means that women are often dependent on the natural environment for subsistence and income. By further limiting women's already constrained access to physical, social, political, and fiscal resources, climate change often burdens women more than men and can magnify existing gender inequality.

The Gender Equality Index is a tool to measure the progress of gender equality in several areas of economic and social life in the EU and its Member States, developed by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). These areas are summarised into a hierarchical structure of domains and sub-domains. The Index consists of 31 indicators and ranges from 1 to 100, with 100 representing a gender-equal society. The aim of the Index is to support evidence-based and informed decision-making in the EU and to track progress and setbacks in gender equality since 2005. Additionally, it helps to understand where improvements are most needed and thus supports policymakers in designing more effective gender equality measures.

Sustainable Development Goal 7 is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015. It aims to "Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all." Access to energy is an important pillar for the wellbeing of the people as well as for economic development and poverty alleviation.

One aspect of energy poverty is lack of access to clean, modern fuels and technologies for cooking. As of 2020, more than 2.6 billion people in developing countries routinely cook with fuels such as wood, animal dung, coal, or kerosene. Burning these types of fuels in open fires or traditional stoves causes harmful household air pollution, resulting in an estimated 3.8 million deaths annually according to the World Health Organization (WHO), and contributes to various health, socio-economic, and environmental problems.

References

- ↑ Winkler H. (2009) Cleaner Energy Cooler Climate, Developing Sustainable Energy Solutions for South Africa, HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- ↑ Munien, S. & Ahmed, F. (2012). A gendered perspective on energy poverty and livelihoods–Advancing the Millennium Development Goals in developing countries. Agenda, 26(1), 112–123.

- ↑ IEA (International Energy Agency). 2015. "World Energy Outlook." Paris: OECD/IEA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 United Nations Development Programme. (2013). Gender and energy. Retrieved January 15, 2020, from https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/gender/Gender%5B%5D and Environment/PB4-AP-Gender-and-Energy.pdf

- 1 2 3 European Institution for Gender Equality (EIGE). (2017). Gender and energy. Retrieved from https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-and-energy Archived 2020-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Jessel, Sonal; Sawyer, Samantha; Hernández, Diana (2019). "Energy, Poverty, and Health in Climate Change: A Comprehensive Review of an Emerging Literature". Frontiers in Public Health. 7: 357. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00357 . ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 6920209 . PMID 31921733.

- ↑ Bank, European Investment (2024-03-07). "EIB Gender equality and women's economic empowerment - Overview 2024".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Gender perspective on access to energy in the EU" (PDF).

- ↑ "Gender and energy" (PDF).

- ↑ Denton, F. (2002). Climate change vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation: Why does gender matter?. Gender & Development, 10(2), 10–20.

- ↑ World Bank. (2011). ‘Gender and Climate Change: Three Things You Should Know’, fact sheet, 2011a, available at: http://go.worldbank.org/TN0KYRX8Q0%5B%5D (accessed 22 October 2012).

- ↑ Sohna, Aminatta Ngum (2016). "Empowering women in Africa through access to substainable energy" (PDF). Africa Development Bank. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ↑ "Maternal Mortality" (PDF). World Health Organisation Fact Sheet. 2015.

- 1 2 Leslie Gray, Alaina Boyle, Erika Francks & Victoria Yu (2019) The power of small-scale solar: gender, energy poverty, and entrepreneurship in Tanzania, Development in Practice, 29:1, 26–39, DOI: 10.1080/09614524.2018.1526257

- ↑ Sule, Ibrahim Kekere; Yusuf, Abdulmalik M.; Salihu, Muhammad-Kabir (March 2022). "Impact of energy poverty on education inequality and infant mortality in some selected African countries". Energy Nexus. 5: 100034. doi: 10.1016/j.nexus.2021.100034 . S2CID 244853164.

- ↑ Karekezi, S., and W. Kithyoma. 2002. "Renewable Energy Strategies for Rural Africa: Is a PV-led Renewable Energy Strategy the Right Approach for Providing Modern Energy to the Rural Poor of Sub-Saharan Africa?" Energy Policy 30 (11): 1071–1086.

- ↑ World Bank. 2017. "World Bank Data." Accessed July 19, 2017. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.ZS Archived 2012-04-12 at the Wayback Machine .

- ↑ Harrison, K., A. Scott, and R. Hogarth. 2016. Accelerating Access to Electricity in Africa With Off-Grid Solar: The Impact of Solar Household Solutions. ODI Report 9. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- ↑ ‘Excess Winter Mortality in England and Wales, 2012/13 (Provisional) and 2011/12 (Final)’, Statistical bulletin, 26 November 2013, Office for National Statistics, United Kingdom, 2013. http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeath-sandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/excesswintermortalityinenglandandwal%5B%5D es/2013-11-26

- 1 2 3 Robinson, C. (2019). Energy poverty and gender in England: A spatial perspective. Geoforum.

- ↑ EIGE (2012), Review of the implementation in the EU of area K of the Beijing Platform for Action: Women and the environment, Gender equality and climate change, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.http://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Gender-Equality-and-Climate-Change-Report.pdf Archived 2021-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Cecelski E. (2004) ‘Re-thinking gender and energy: Old and new directions’, in ENERGIA/EASE Discussion Paper, p. 41, 49

- ↑ Pueyo, A. & Maestre, M. (2019). Linking energy access, gender and poverty: A review of the literature on productive uses of energy. Energy Research & Social Science, 53, 170–181.