Harriet Jacobs was an African-American abolitionist and writer whose autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent, is now considered an "American classic". Born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina, she was sexually harassed by her enslaver. When he threatened to sell her children if she did not submit to his desire, she hid in a tiny crawl space under the roof of her grandmother's house, so low she could not stand up in it. After staying there for seven years, she finally managed to escape to the free North, where she was reunited with her children Joseph and Louisa Matilda and her brother John S. Jacobs. She found work as a nanny and got into contact with abolitionist and feminist reformers. Even in New York City, her freedom was in danger until her employer was able to pay off her legal owner.

"Children of the plantation" is a euphemism used to refer to people with ancestry tracing back to the time of slavery in the United States in which the offspring was born to black African female slaves in the context of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and European men, usually the slave's owner, one of the owner's relatives, or the plantation overseer. These children were often considered to be the property of the slave owner and were often subjected to the same treatment as other slaves on the plantation. Many of these children were born into slavery and had no legal rights, as they were not recognized as the legitimate children of their fathers. This practice was a form of sexual abuse and exploitation, as the European men who fathered these children often used their power and authority to force themselves upon the black females who were under their control. The trauma and suffering that these children and their mothers experienced as a result of this practice continue to have a lasting impact on the African American community.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself is an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs, a mother and fugitive slave, published in 1861 by L. Maria Child, who edited the book for its author. Jacobs used the pseudonym Linda Brent. The book documents Jacobs's life as a slave and how she gained freedom for herself and for her children. Jacobs contributed to the genre of slave narrative by using the techniques of sentimental novels "to address race and gender issues." She explores the struggles and sexual abuse that female slaves faced as well as their efforts to practice motherhood and protect their children when their children might be sold away.

Clotel; or, The President's Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States is an 1853 novel by United States author and playwright William Wells Brown about Clotel and her sister, fictional slave daughters of Thomas Jefferson. Brown, who escaped from slavery in 1834 at the age of 20, published the book in London. He was staying after a lecture tour to evade possible recapture due to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Set in the early nineteenth century, it is considered the first novel published by an African American and is set in the United States. Three additional versions were published through 1867.

Margaret Garner, called "Peggy", was an enslaved African-American woman in pre-Civil War America who killed her own daughter rather than allow the child to be returned to slavery. Garner and her family had escaped enslavement in January 1856 by traveling across the frozen Ohio River to Cincinnati, but they were apprehended by U.S. Marshals acting under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Garner's defense attorney, John Jolliffe, moved to have her tried for murder in Ohio, to be able to get a trial in a free state and to challenge the Fugitive Slave Law. Garner's story was the inspiration for the novel Beloved (1987) by Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison and its subsequent adaptation into a film of the same name starring Oprah Winfrey (1998).

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of slave mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. This institutionalized the white male rape of black women in the colonies, refiguring Black women as not only free labor but also unlimited capital, who could both produce and reproduce for the benefit of the patriarch. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property.

James Madison Hemings was the son of the mixed-race enslaved woman Sally Hemings and, according to most Jefferson scholars, her enslaver, President Thomas Jefferson. He was the third of her four children to survive to adulthood. Born into slavery, according to partus sequitur ventrem, Hemings grew up on Jefferson's Monticello plantation, where his mother was also enslaved. After some light duties as a young boy, Hemings became a carpenter and fine woodwork apprentice at around age 14 and worked in the joiner's shop until he was about 21. He learned to play the violin and was able to earn money by growing cabbages. Jefferson died in 1826, after which Sally Hemings was "given her time" by Jefferson's surviving daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph.

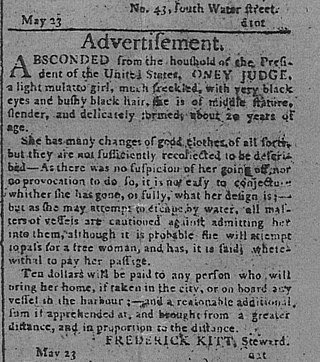

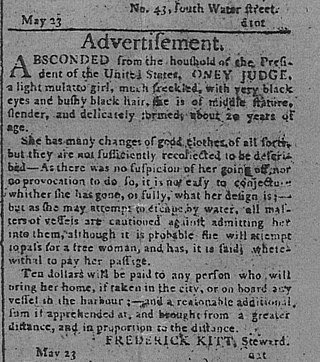

Ona "Oney" Judge Staines was a biracial woman who was enslaved by the Washington family, first at the family's plantation at Mount Vernon and later, after George Washington became president, at the President's House in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital city. In her early twenties, she absconded, becoming a fugitive slave, after learning that Martha Washington had intended to transfer ownership of her to her granddaughter, known to have a horrible temper. She fled to New Hampshire, where she married, had children, and converted to Christianity. Though she was never formally freed, the Washington family ultimately stopped pressing her to return to Virginia after George Washington's death.

John Casor, a servant in Northampton County in the Virginia Colony, in 1655 became the first person of African descent and second person in the Thirteen Colonies to be declared as a slave for life as a result of a civil suit. In 1662, the Virginia Colony passed a law incorporating the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, ruling that children of enslaved mothers would be born into slavery, regardless of their father's race or status. This was in contradiction to English common law for English subjects, which based a child's status on that of the father. In 1699 the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a law deporting all free black people. But many new families of free black people continued to be formed during the colonial years by the close relationships among the working class.

Emanuel Driggus and his wife Frances were Atlantic Creole slaves in the mid-seventeenth century in Virginia, of the Chesapeake Bay Colony. The name Driggus is likely a corruption of the Portuguese name Rodrigues as he was born in the Portuguese colony of Ndongo.

The institution of slavery in North America existed from the earliest years of the colonial history of the United States until 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States except as punishment for a crime. It was also abolished among the sovereign Indian tribes in Indian Territory by new peace treaties which the US required after the Civil War.

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission, emancipation, or self-purchase. A fugitive slave is a person who escaped enslavement by fleeing.

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (or Greenstead) (1630 – January 20, 1665) was one of the first black people of the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Key won her freedom and that of her infant son John Grinstead on July 21, 1656, in the colony of Virginia.

Marguerite Scypion, also known in court files as Marguerite, was an African-Natchez woman, born into slavery in St. Louis, then located in French Upper Louisiana. She was held first by Joseph Tayon and later by Jean Pierre Chouteau, one of the most powerful men in the city.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by slaves against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

Hudgins v. Wright (1806) was a freedom suit decided in the favor of the slave Jackey Wright by the Virginia Supreme Court. She had sued for freedom for herself and her two children based on her claim of descent from Indian women. Indian slavery had been prohibited in Virginia since 1705. Since 1662, slave law had incorporated the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, saying that children born in the colony took the social status of their mothers.

Alice Clifton was an enslaved African-American woman owned by John Bartholomew in Philadelphia. She was brought to trial on April 18, 1787, for the murder of her infant daughter, found guilty, and sentenced to death. Following the sentence, a mob formed in order to prevent her execution out of protest for unjust circumstances because she was coerced into killing her baby by the father of the child, Jack Shaffer. At the time of the trial, Clifton was between fifteen and sixteen years old. Clifton was mentioned in only one primary source known to date, the court record for her case.

"The Quadroons" is a short story written by American writer Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880) and published in The Liberty Bell in 1842. The influential short story depicts the life and death of a mixed-race woman and her daughter in early nineteenth century America, a slave-owning society.

John Graweere also known as John Gowen was one of the First Africans in Virginia, who was a servant who earned enough money to pay for his son's freedom. He filed a lawsuit to free his son, arguing that he wanted to raise him as a Christian. The court agreed and freed the son.