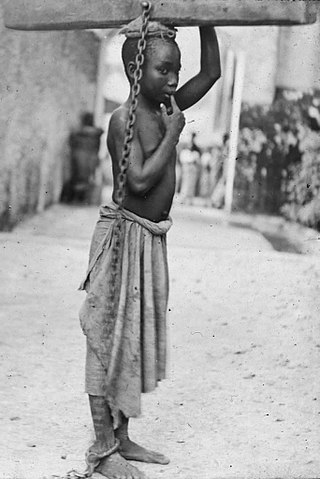

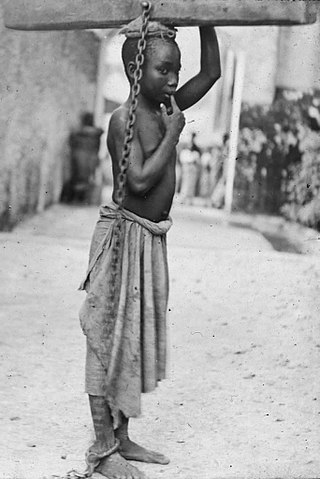

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved people around the world.

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States refers to the institution of slavery as it existed in the European colonies which eventually became part of the United States. In these colonies, slavery developed due to a combination of factors, primarily the labour demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies, which had resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were victims of enslavement by European colonizers during the era.

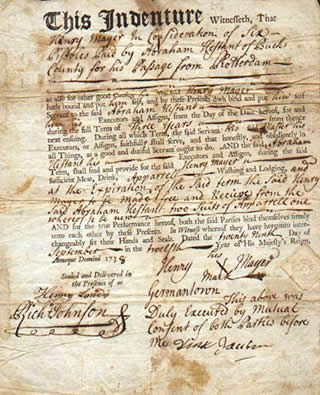

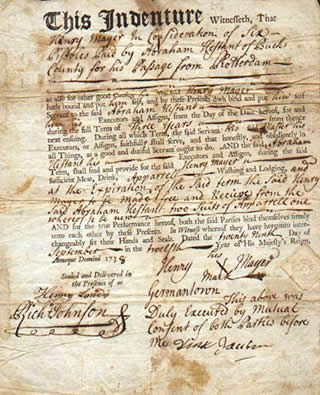

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, or imposed involuntarily as a judicial punishment. Many came with forged or no contract they ever saw.

Slavery in New Jersey began in the early 17th century, when Dutch colonists trafficked African slaves for labor to develop the colony of New Netherland. After England took control of the colony in 1664, its colonists continued the importation of slaves from Africa. They also imported "seasoned" slaves from their colonies in the West Indies and enslaved Native Americans from the Carolinas.

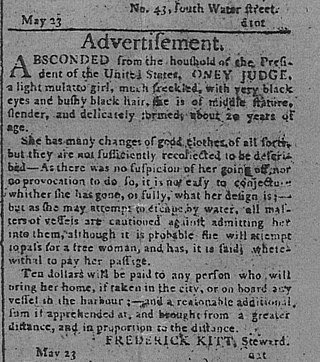

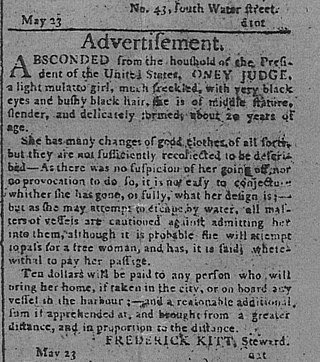

Ona "Oney" Judge Staines was a biracial woman who was enslaved by the Washington family, first at the family's plantation at Mount Vernon and later, after George Washington became president, at the President's House in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital city. In her early twenties, she absconded, becoming a fugitive slave, after learning that Martha Washington had intended to transfer ownership of her to her granddaughter, known to have a horrible temper. She fled to New Hampshire, where she married, had children, and converted to Christianity. Though she was never formally freed, the Washington family ultimately stopped pressing her to return to Virginia after George Washington's death.

The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, were a series of laws enacted by the Colony of Virginia's House of Burgesses in 1705 regulating the interactions between slaves and citizens of the crown colony of Virginia. The enactment of the Slave Codes is considered to be the consolidation of slavery in Virginia, and served as the foundation of Virginia's slave legislation. All servants from non-Christian lands became slaves. There were forty one parts of this code each defining a different part and law surrounding the slavery in Virginia. These codes overruled the other codes in the past and any other subject covered by this act are canceled.

The New-York Manumission Society was an American organization founded in 1785 by U.S. Founding Father John Jay, among others, to promote the gradual abolition of slavery and manumission of slaves of African descent within the state of New York. The organization was made up entirely of white men, most of whom were wealthy and held influential positions in society. Throughout its history, which ended in 1849 after the abolition of slavery in New York, the society battled against the slave trade, and for the eventual emancipation of all the slaves in the state. It founded the African Free School for the poor and orphaned children of slaves and free people of color.

John Casor, a servant in Northampton County in the Colony of Virginia, in 1655 became one of the first people of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be enslaved for life as a result of a civil suit.

Slavery was practiced in Massachusetts bay by Native Americans before European settlement, and continued until its abolition in the 1700s. Although slavery in the United States is typically associated with the Caribbean and the Antebellum American South, enslaved people existed to a lesser extent in New England: historians estimate that between 1755 and 1764, the Massachusetts enslaved population was approximately 2.2 percent of the total population; the slave population was generally concentrated in the industrial and coastal towns. Unlike in the American South, enslaved people in Massachusetts had legal rights, including the ability to file legal suits in court.

The trafficking of enslaved Africans to what became New York began as part of the Dutch slave trade. The Dutch West India Company trafficked eleven enslaved Africans to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction held in New Amsterdam in 1655. With the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies, more than 42% of New York City households enslaved African people by 1703, often as domestic servants and laborers. Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Enslaved Africans were also used in farming on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley, as well as the Mohawk Valley region.

Christopher Sheels, was a slave and house servant at George Washington's plantation, Mount Vernon, in Virginia, United States.

Slavery among Native Americans in the United States includes slavery by and enslavement of Native Americans roughly within what is currently the United States of America.

An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the Fifth Pennsylvania General Assembly on 1 March 1780, prescribed an end for slavery in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the United States. It was the first slavery abolition act in the course of human history to be adopted by an elected body.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

John Punch was an enslaved African who lived in the colony of Virginia. Thought to have been an indentured servant, Punch attempted to escape to Maryland and was sentenced in July 1640 by the Virginia Governor's Council to serve as a slave for the remainder of his life. Two European men who ran away with him received a lighter sentence of extended indentured servitude. For this reason, some historians consider John Punch the "first official slave in the English colonies," and his case as the "first legal sanctioning of lifelong slavery in the Chesapeake." Some historians also consider this to be one of the first legal distinctions between Europeans and Africans made in the colony, and a key milestone in the development of the institution of slavery in the United States.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the late colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Slavery was legally practiced in the Province of North Carolina and the state of North Carolina until January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Prior to statehood, there were 41,000 enslaved African-Americans in the Province of North Carolina in 1767. By 1860, the number of slaves in the state of North Carolina was 331,059, about one third of the total population of the state. In 1860, there were nineteen counties in North Carolina where the number of slaves was larger than the free white population. During the antebellum period the state of North Carolina passed several laws to protect the rights of slave owners while disenfranchising the rights of slaves. There was a constant fear amongst white slave owners in North Carolina of slave revolts from the time of the American Revolution. Despite their circumstances, some North Carolina slaves and freed slaves distinguished themselves as artisans, soldiers during the Revolution, religious leaders, and writers.

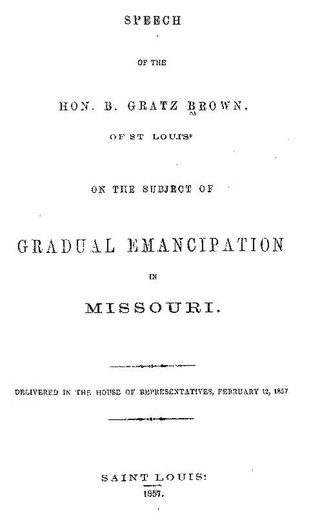

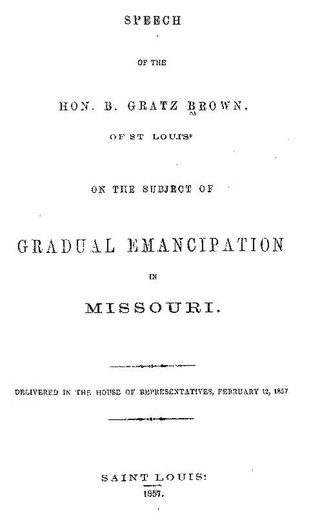

Gradual emancipation was a legal mechanism used by some states to abolish slavery over some time, such as An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery of 1780 in Pennsylvania.

Polly Strong was an enslaved woman in the Northwest Territory, in present-day Indiana. She was born after the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery. Slavery was prohibited by the Constitution of Indiana in 1816. Two years later, Strong's mother Jenny and attorney Moses Tabbs asked for a writ of habeas corpus for Polly and her brother James in 1818. Judge Thomas H. Blake produced indentures, Polly for 12 more years and James for four more years of servitude. The case was dismissed in 1819.