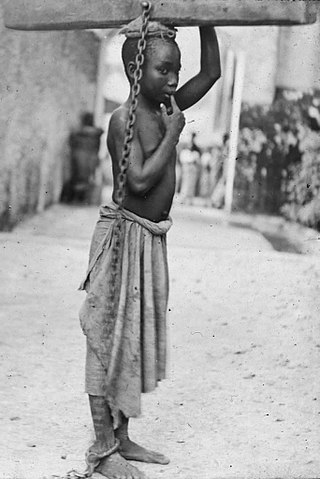

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate slaves around the world.

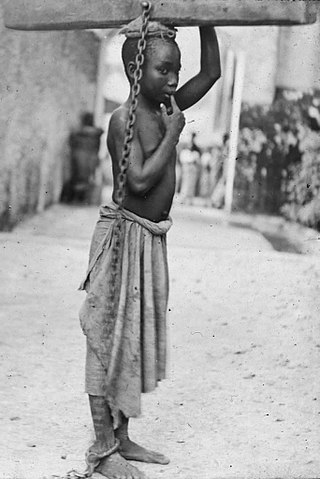

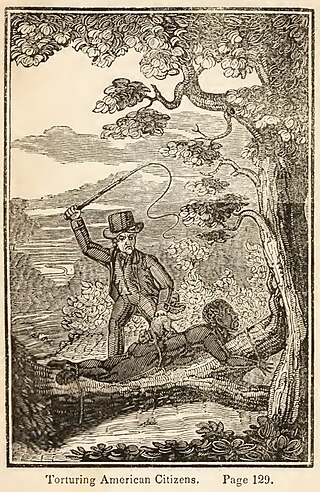

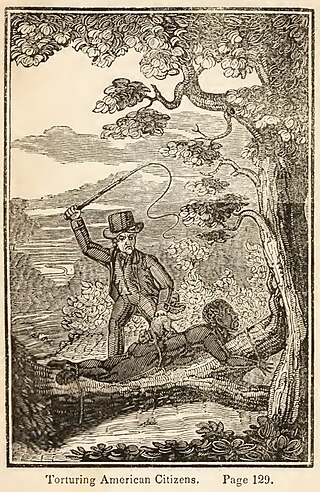

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states to be politically imperative that the number of free states not exceed the number of slave states, so new states were admitted in slave–free pairs. There were, nonetheless, some slaves in most free states up to the 1840 census, and the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution, as implemented by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, provided that a slave did not become free by entering a free state and must be returned to his or her owner.

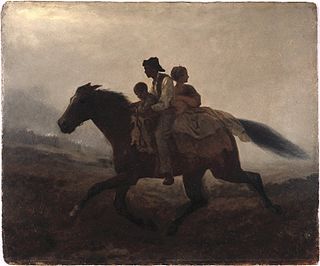

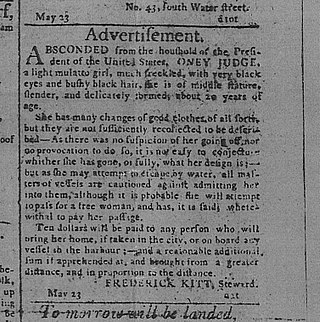

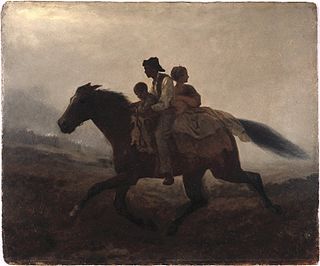

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freedom seekers to avoid implying that the enslaved person had committed a crime and that the slaveholder was the injured party.

Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. 539 (1842), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court held that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 precluded a Pennsylvania state law that prohibited Blacks from being taken out of the free state of Pennsylvania into slavery. The Court overturned the conviction of slavecatcher Edward Prigg as a result.

In the context of slavery in the United States, the personal liberty laws were laws passed by several U.S. states in the North to counter the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Different laws did this in different ways, including allowing jury trials for escaped slaves and forbidding state authorities from cooperating in their capture and return. States with personal liberty laws included Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Vermont.

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from the Fugitive Slave Clause which is in the United States Constitution. It was thought that forcing states to deliver fugitive slaves back to enslavement violated states' rights due to state sovereignty and was believed that seizing state property should not be left up to the states. The Fugitive Slave Clause states that fugitive slaves "shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due", which abridged state rights because forcing people back into slavery was a form of retrieving private property. The Compromise of 1850 entailed a series of laws that allowed slavery in the new territories and forced officials in free states to give a hearing to slave-owners without a jury.

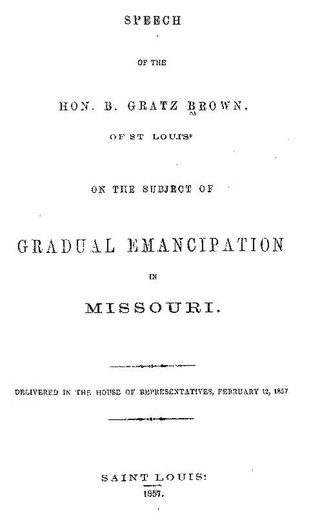

Compensated emancipation was a method of ending slavery, under which the enslaved person's owner received compensation from the government in exchange for manumitting the slave. This could be monetary, and it could allow the owner to retain the slave for a period of labor as an indentured servant. Cash compensation rarely was equal to the slave's market value.

Slavery in New Jersey began in the early 17th century, when Dutch colonists trafficked African slaves for labor to develop the colony of New Netherland. After England took control of the colony in 1664, its colonists continued the importation of slaves from Africa. They also imported "seasoned" slaves from their colonies in the West Indies and enslaved Native Americans from the Carolinas.

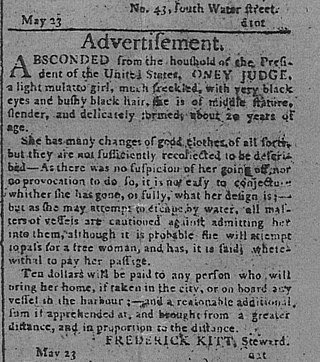

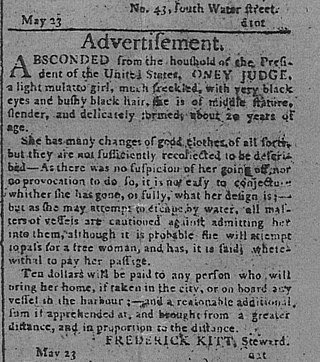

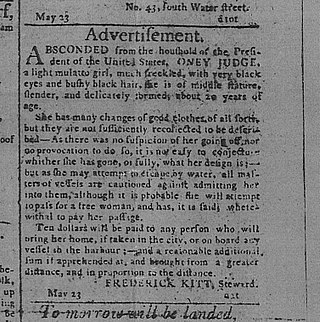

Ona "Oney" Judge Staines was a biracial woman who was enslaved by the Washington family, first at the family's plantation at Mount Vernon and later, after George Washington became president, at the President's House in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital city. In her early twenties, she absconded, becoming a fugitive slave, after learning that Martha Washington had intended to transfer ownership of her to her granddaughter, known to have a horrible temper. She fled to New Hampshire, where she married, had children, and converted to Christianity. Though she was never formally freed, the Washington family ultimately stopped pressing her to return to Virginia after George Washington's death.

The New-York Manumission Society was an American organization founded in 1785 by U.S. Founding Father John Jay, among others, to promote the gradual abolition of slavery and manumission of slaves of African descent within the state of New York. The organization was made up entirely of white men, most of whom were wealthy and held influential positions in society. Throughout its history, which ended in 1849 after the abolition of slavery in New York, the society battled against the slave trade, and for the eventual emancipation of all the slaves in the state. It founded the African Free School for the poor and orphaned children of slaves and free people of color.

Slavery was practiced in Massachusetts bay by Native Americans before European settlement, and continued until its abolition in the 1700s. Although slavery in the United States is typically associated with the Caribbean and the Antebellum American South, enslaved people existed to a lesser extent in New England: historians estimate that between 1755 and 1764, the Massachusetts enslaved population was approximately 2.2 percent of the total population; the slave population was generally concentrated in the industrial and coastal towns. Unlike in the American South, enslaved people in Massachusetts had legal rights, including the ability to file legal suits in court.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Hercules Posey was an enslaved African owned by George Washington, at his plantation Mount Vernon in Virginia. "Uncle Harkless," as he was called by George Washington Parke Custis, served as chief cook at the Mansion House for many years. In November 1790, Hercules was one of eight enslaved Africans brought by President Washington to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, then the temporary national capital, to serve in the household of the third presidential mansion.

Christopher Sheels, was a slave and house servant at George Washington's plantation, Mount Vernon, in Virginia, United States.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the late colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

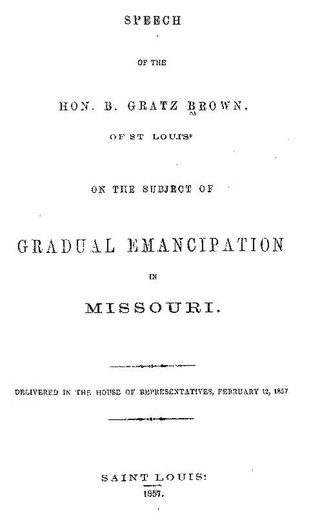

Gradual emancipation was a legal mechanism used by some states to abolish slavery over some time, such as An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery of 1780 in Pennsylvania.

In the District of Columbia, the slave trade was legal from its creation until it was outlawed as part of the Compromise of 1850. That restrictions on slavery in the District were probably coming was a major factor in the retrocession of the Virginia part of the District back to Virginia in 1847. Thus the large slave-trading businesses in Alexandria, such as Franklin & Armfield, could continue their operations in Virginia, where slavery was more secure.

Following the creation of the United States in 1776 and the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1789, the legal status of slavery was generally a matter for individual U.S. state legislatures and judiciaries As such, slavery flourished in some states, and withered on the vine in others. On the whole, the former Thirteen Colonies abolished slavery relatively slowly, if at all, with several Northern states using gradual emancipation systems in which freedom would be granted after so many years of life or service.