Egungun, in the broadest sense is any Yoruba masquerade or masked, costumed figure. More specifically, it is a Yoruba masquerade for ancestor reverence, or the ancestors themselves as a collective force. Eégún is the reduced form of the word egúngún and has the same meaning. There is a misconception that Egun or Eegun is the singular form, or that it represents the ancestors while egúngún is the masquerade or the plural form. This misconception is common in the Americas by Orisa devotees that do not speak Yorùbá language as a vernacular. Egungun is a visible manifestation of the spirits of departed ancestors who periodically revisit the human community for remembrance, celebration, and blessings.

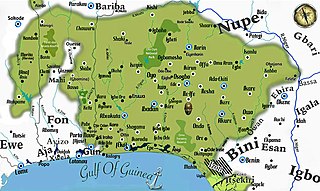

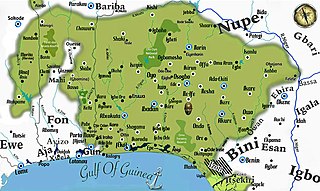

Yorubaland is the homeland and cultural region of the Yoruba people in West Africa. It spans the modern-day countries of Nigeria, Togo and Benin, and covers a total land area of 142,114 km2 (54,871 sq mi). Of this land area, 106,016 km2 (74.6%) lies within Nigeria, 18.9% in Benin, and the remaining 6.5% is in Togo. Prior to European colonization, a portion of this area was known as Yoruba country. The geo-cultural space contains an estimated 55 million people, the majority of this population being ethnic Yoruba.

The Gẹlẹdẹ spectacle of the Yoruba is a public display by colorful masks which combines art and ritual dance to amuse, educate and inspire worship. Gelede celebrates “Mothers”, a group that includes female ancestors and deities as well as the elderly women of the community, and the power and spiritual capacity these women have in society. Focusing not only on fertility and motherhood but also on correct social behavior within the Yoruba society.

The Akoko are a large Yoruba cultural sub-group in the Northeastern part of Yorubaland. The area spans from Ondo State to Edo State in southwest Nigeria. The Akokos as a subgroup make up 20.3% of the population of Ondo State, and 5.7% of the population of Edo State. Out of the present 18 Local Government Councils it constitutes four; Akoko North-East, Akoko North-West, Akoko South-East and Akoko South-West, as well as the Akoko Edo LGA of Edo State. The Adekunle Ajasin University, a state owned university with a capacity for about 20,000 tertiary education students and more than 50 departments in seven faculties is located in Akungba-Akoko. A state specialist hospital is situated at Ikare Akoko, while community general hospitals are located in Oka-Akoko and Ipe-Akoko.

Ibeji is the name of an Orisha representing a pair of divine twins in the Yoruba religion of the Yoruba people. In the diasporic Yoruba spirituality of Latin America, Ibeji are syncretized with Saints Cosmas and Damian. In Yoruba culture and spirituality, twins are believed to be magical, and are granted protection by the Orisha Shango. If one twin should die, it represents bad fortune for the parents and the society to which they belong. The parents therefore commission a babalawo to carve a wooden Ibeji to represent the deceased twin, and the parents take care of the figure as if it were a real person. Other than the sex, the appearance of the Ibeji is determined by the sculptor. The parents then dress and decorate the ibeji to represent their own status, using clothing made from cowrie shells, as well as beads, coins, and paint.

The Ìgbómìnà are a subgroup of the Yoruba ethnic group, which originates from the north central and southwest Nigeria. They speak a dialect called Ìgbómìnà or Igbonna, classified among the Central Yoruba of the three major Yoruba dialectical areas. The Ìgbómìnà spread across what is now southern Kwara State and northern Osun State. Peripheral areas of the dialectical region have some similarities to the adjoining Ekiti, Ijesha and Oyo dialects. Idoba is on Owode Ofaro Land

The Oṣun River, Yoruba: Odò Ọ̀ṣun, is a river of Yorubaland that rises in Ekiti State and flows westwards into Osun State before turning southwestwards at its confluence with the Erinle River near the town of Ede and then heading south at the Asejire reservoir flowing though the rest of the state and Ogun State in Southwestern Nigeria before eventually discharging into the Lekki Lagoon and the Atlantic at the Gulf of Guinea.

Ogboni is a fraternal institution indigenous to the Yoruba-speaking polities of Nigeria, Republic of Bénin and Togo, as well as among the Edo people. The society performs a range of political and religious functions, including exercising a profound influence on monarchs and serving as high courts of jurisprudence in capital offenses.

Traditional African masks are worn in ceremonies and rituals across West, Central, and Southern Africa. They are used in events such as harvest celebrations, funerals, rites of passage, weddings, and coronations. Some societies also use masks to resolve disputes and conflicts.

Most African sculpture was historically in wood and other organic materials that have not survived from earlier than at most a few centuries ago; older pottery figures are found from a number of areas. Masks are important elements in the art of many peoples, along with human figures, often highly stylized. There is a vast variety of styles, often varying within the same context of origin depending on the use of the object, but wide regional trends are apparent; sculpture is most common among "groups of settled cultivators in the areas drained by the Niger and Congo rivers" in West Africa. Direct images of African deities are relatively infrequent, but masks in particular are or were often made for traditional African religious ceremonies; today many are made for tourists as "airport art". African masks were an influence on European Modernist art, which was inspired by their lack of concern for naturalistic depiction.

The Yoruba of West Africa are responsible for a distinct artistic tradition in Africa, a tradition that remains vital and influential today.

Igbo art is any piece of visual art originating from the Igbo people. The Igbo produce a wide variety of art including traditional figures, masks, artifacts and textiles, plus works in metals such as bronze. Artworks from the Igbo have been found from as early as 9th century with the bronze artifacts found at Igbo Ukwu. With processes of colonialism and the opening of Nigeria to Western influences, the vocabulary of fine art and art history came to interact with established traditions. Therefore, the term can also refer to contemporary works of art produced in response to global demands and interactions.

The Yoruba people are a West African ethnic group who mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by the Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute more than 50 million people in Africa, are over a million outside the continent, and bear further representation among members of the African diaspora. The vast majority of the Yoruba population is today within the country of Nigeria, where they make up 20.7% of the country's population according to Ethnologue estimations, making them one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa. Most Yoruba people speak the Yoruba language, which is the Niger-Congo language with the largest number of native or L1 speakers.

Omuo-Ekiti is an ancient town in the eastern part of Ekiti State in western Nigeria, and the seat of the Ekiti-East local government. Being inside Yorubaland, its population and that of Ekiti State are mainly the Yoruba It is located on the border of the state of Ondo.

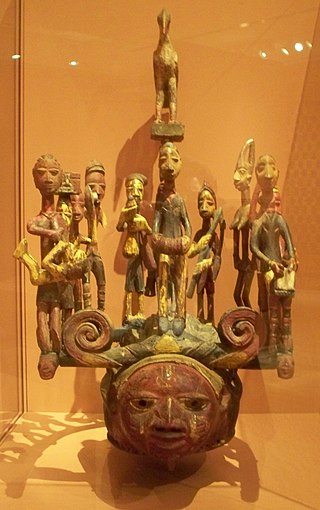

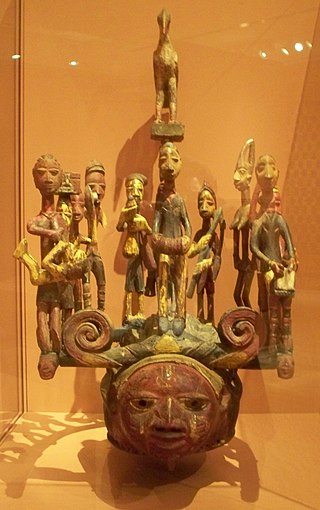

This Magbo helmet mask for an Oro society member was created by Yoruba artist Onabanjo of Itu Meko. It is currently located in the African collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, which is in Indianapolis, Indiana. Created around 1880-1910, it depicts a varied cast of community members carved of wood, colored with pigment, and mounted on a curved bar surmounting the helmet.

The Okun people are a Yoruba speaking people found majorly in Kogi, but with settlements in Kwara, Ekiti, and Ondo states of Nigeria. Their dialects are generally classified in the Northeast Yoruba language (NEY) grouping. They are collectively called "Okun", which in Okun dialects could mean "Sorry", "Well-done", or as an all-encompassing greeting. Similarly, this form of greeting is also found among the Ekiti and Igbomina groups of Yoruba people. It is also a mode of greeting among the Ijesa people of southwestern Nigeria.

The Ekiti people are one of the largest historical subgroups of the larger Yoruba people of West Africa, located in Nigeria. They are classified as a Central Yoruba group, alongside the Ijesha, Igbomina, Yagba and Ifes. Ekiti State is populated exclusively by Ekiti people; however, it is but a segment of the historic territorial domain of Ekiti-speaking groups, which historically included towns in Ondo State such as Akure, Ilara-Mokin, Ijare, and Igbara-oke. Ogbagi, Irun, Ese, Oyin, Igasi, Afin and Eriti in the Akoko region, as well as some towns in Kwara State, are also culturally Ekiti, although belong in other states today.

Odo Ere, popularly called Ere Gajo, is the headquarters of Yagba West Local Government Area, Kogi State, Nigeria. The town is located in the old Kabba Province about 140 kilometres southeast of Ilorin. The people of Odo Ere share a common ancestry with the Yoruba people in South-West Nigeria and they are often referred to as Okun Yoruba people. The town is situated on a well-watered savannah plain consisting of dotted hills, forest and grassland. The topography earned the town the sobriquet: Ere Ọmọ Onilẹ Dun Rin, meaning "Odo Ere town with a beautiful flat terrain that enhances ease of movement".

Yam is a staple food in West Africa and other regions classified as a tuber crop and it is an annual or perennial crop. The New Yam festival is celebrated by almost every ethnic group in Nigeria and is observed annually at the end of June.

The Ibadan National Museum of Unity is an ethnographic museum in Aleshinloye Ibadan, Nigeria. The museum is dedicated to the culture of the different ethnic groups of Nigeria.