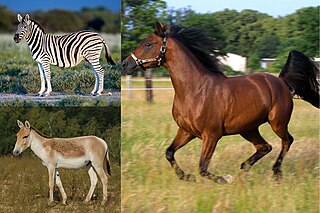

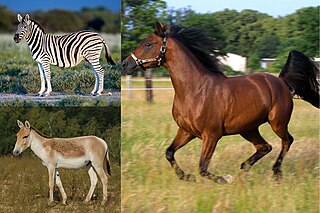

Equidae is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. The family evolved around 50 million years ago from a small, multi-toed ungulate into larger, single-toed animals. All extant species are in the genus Equus, which originated in North America. Equidae belongs to the order Perissodactyla, which includes the extant tapirs and rhinoceros, and several extinct families.

How and when horses became domesticated has been disputed. Although horses appeared in Paleolithic cave art as early as 30,000 BC, these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat. The clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials dated c. 2000 BC. However, an increasing amount of evidence began to support the hypothesis that horses were domesticated in the Eurasian Steppes in approximately 3500 BC. Discoveries in the context of the Botai culture had suggested that Botai settlements in the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan are the location of the earliest domestication of the horse. Warmouth et al. (2012) pointed to horses having been domesticated around 3000 BC in what is now Ukraine and Western Kazakhstan.

Przewalski's horse, also called the takhi, Mongolian wild horse or Dzungarian horse, is a rare and endangered horse originally native to the steppes of Central Asia. It is named after the Russian geographer and explorer Nikolay Przhevalsky. Once extinct in the wild, since the 1990s it has been reintroduced to its native habitat in Mongolia in the Khustain Nuruu National Park, Takhin Tal Nature Reserve, and Khomiin Tal, as well as several other locales in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

The tarpan was a free-ranging horse subspecies of the Eurasian steppe from the 18th to the 20th century. It is generally unknown whether those horses represented genuine wild horses, feral domestic horses or hybrids. The last individual believed to be a tarpan died in captivity in the Russian Empire in 1909.

Equus is a genus of mammals in the family Equidae, which includes horses, asses, and zebras. Within the Equidae, Equus is the only recognized extant genus, comprising seven living species. Like Equidae more broadly, Equus has numerous extinct species known only from fossils. The genus most likely originated in North America and spread quickly to the Old World. Equines are odd-toed ungulates with slender legs, long heads, relatively long necks, manes, and long tails. All species are herbivorous, and mostly grazers, with simpler digestive systems than ruminants but able to subsist on lower-quality vegetation.

The kiang is the largest of the Asinus subgenus. It is native to the Tibetan Plateau in Ladakh India, northern Pakistan, Tajikistan, China and northern Nepal. It inhabits montane grasslands and shrublands. Other common names for this species include Tibetan wild ass, khyang and gorkhar.

Equus scotti is an extinct species of horse native to Pleistocene North America.

The wild horse is a species of the genus Equus, which includes as subspecies the modern domesticated horse as well as the endangered Przewalski's horse. The European wild horse, also known as the tarpan, that went extinct in the late 19th or early 20th century has previously been treated as the nominate subspecies of wild horse, Equus ferus ferus, but more recent studies have cast doubt on whether tarpans were truly wild or if they actually were feral horses or hybrids.

Wild horse is a species of the genus Equus that includes domesticated and undomesticated subspecies.

The European wild ass or hydruntine is an extinct equine from the Middle Pleistocene to Late Holocene of Europe and West Asia, and possibly North Africa. It is a member of the subgenus Asinus, and closely related to the living Asiatic wild ass. The specific epithet, hydruntinus, means from Otranto.

The horse has been present in the Indian subcontinent from at least the middle of the second millennium BC, more than two millennia after its domestication in Central Asia. The earliest uncontroversial evidence of horse remains on the Indian Subcontinent date to the early Swat culture. While horse remains and related artifacts have been found in Late Harappan sites, indicating that horses may have been present at Late Harappan times, horses did not play an essential role in the Harappan civilisation, in contrast to the Vedic period. The importance of the horse for the Indo-Aryans is indicated by the Sanskrit word Ashva, "horse," which is often mentioned in the Vedas and Hindu scriptures.

The evolution of the horse, a mammal of the family Equidae, occurred over a geologic time scale of 50 million years, transforming the small, dog-sized, forest-dwelling Eohippus into the modern horse. Paleozoologists have been able to piece together a more complete outline of the evolutionary lineage of the modern horse than of any other animal. Much of this evolution took place in North America, where horses originated but became extinct about 10,000 years ago, before being reintroduced in the 15th century.

Equus simplicidens, sometimes known as the Hagerman horse or the American zebra is an extinct species in the horse family native to North America during the Pliocene and Early-Late Pleistocene. It is one of the oldest and most primitive members of the genus Equus. Abundant remains of it were discovered in 1928 in Hagerman, Idaho. It is the state fossil of Idaho.

Cormohipparion is an extinct genus of horse belonging to the tribe Hipparionini that lived in North America during the late Miocene to Pliocene. They grew up to 3 feet long.

Haringtonhippus is an extinct genus of equine from the Pleistocene of North America The genus is monospecific, consisting of the species H. francisci, initially described in 1915 by Oliver Perry Hay as Equus francisci. Members of the genus are often referred to as stilt-legged horses, in reference to their slender distal limb bones, in contrast with those of contemporary "stout legged" caballine true horses.

The history of horse domestication has been subject to much debate, with various competing hypotheses over time about how domestication of the horse occurred. The main point of contention was whether the domestication of the horse occurred once in a single domestication event, or that the horse was domesticated independently multiple times. The debate was resolved at the beginning of the 21st century using DNA evidence that favored a mixed model in which domestication of the stallion most likely occurred only once, while wild mares of various regions were included in local domesticated herds.

Horses have been an important component of American life and culture since before the founding of the nation. In 2008, there were an estimated 9.2 million horses in the United States, with 4.6 million citizens involved in businesses related to horses. There are an estimated 82,000 feral horses that roam freely in the wild in certain parts of the country, mostly in the Western United States.

Equus stenonis is an extinct species of equine that lived in Western Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene epoch.

Gallic horse, also known as Equus caballus gallicus, is a prehistoric subspecies of Equus caballus that lived in the Upper Paleolithic. It first appeared in the Aurignacian period because of climatic changes and roamed the territory of present-day France during the Gravettian and up to the end of the Solutrean. Its fossils, dated from 40,000 to around 15,000 years BC, are close to those of Equus caballus germanicus and may not correspond to a valid subspecies. First described by François Prat in 1968, it is around 1.40 m (4.6 ft) tall and differs from Equus caballus germanicus mainly in its dentition and slightly smaller size.