The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all animals with lungs. The trachea extends from the larynx and branches into the two primary bronchi. At the top of the trachea the cricoid cartilage attaches it to the larynx. The trachea is formed by a number of horseshoe-shaped rings, joined together vertically by overlying ligaments, and by the trachealis muscle at their ends. The epiglottis closes the opening to the larynx during swallowing.

The esophagus or oesophagus, colloquially known also as the food pipe, food tube, or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus is a fibromuscular tube, about 25 cm (10 in) long in adults, that travels behind the trachea and heart, passes through the diaphragm, and empties into the uppermost region of the stomach. During swallowing, the epiglottis tilts backwards to prevent food from going down the larynx and lungs. The word oesophagus is from Ancient Greek οἰσοφάγος (oisophágos), from οἴσω (oísō), future form of φέρω + ἔφαγον.

Tracheomalacia is a condition or incident where the cartilage that keeps the airway (trachea) open is soft such that the trachea partly collapses especially during increased airflow. This condition is most commonly seen in infants and young children. The usual symptom is stridor when a person breathes out. This is usually known as a collapsed windpipe.

In anatomy, a fistula is an abnormal connection joining two hollow spaces, such as blood vessels, intestines, or other hollow organs to each other, often resulting in an abnormal flow of fluid from one space to the other. An anal fistula connects the anal canal to the perianal skin. An anovaginal or rectovaginal fistula is a hole joining the anus or rectum to the vagina. A colovaginal fistula joins the space in the colon to that in the vagina. A urinary tract fistula is an abnormal opening in the urinary tract or an abnormal connection between the urinary tract and another organ. An abnormal communication between the bladder and the uterus is called a vesicouterine fistula, while if it is between the bladder and the vagina it is known as a vesicovaginal fistula, and if between the urethra and the vagina: a urethrovaginal fistula. When occurring between two parts of the intestine, it is known as an enteroenteral fistula, between the small intestine and the skin as an enterocutaneous fistula, and between the colon and the skin as a colocutaneous fistula.

Laryngectomy is the removal of the larynx and separation of the airway from the mouth, nose and esophagus. In a total laryngectomy, the entire larynx is removed. In a partial laryngectomy, only a portion of the larynx is removed. Following the procedure, the person breathes through an opening in the neck known as a stoma. This procedure is usually performed by an ENT surgeon in cases of laryngeal cancer. Many cases of laryngeal cancer are treated with more conservative methods. A laryngectomy is performed when these treatments fail to conserve the larynx or when the cancer has progressed such that normal functioning would be prevented. Laryngectomies are also performed on individuals with other types of head and neck cancer. Less invasive partial laryngectomies, including tracheal shaves and feminization laryngoplasty may also be performed on transgender women and other female or non-binary identified individuals to feminize the larynx and/or voice. Post-laryngectomy rehabilitation includes voice restoration, oral feeding and more recently, smell and taste rehabilitation. An individual's quality of life can be affected post-surgery.

A tracheoesophageal fistula is an abnormal connection (fistula) between the esophagus and the trachea. TEF is a common congenital abnormality, but when occurring late in life is usually the sequela of surgical procedures such as a laryngectomy.

Pediatric surgery is a subspecialty of surgery involving the surgery of fetuses, infants, children, adolescents, and young adults.

Atresia is a condition in which an orifice or passage in the body is closed or absent.

An imperforate anus or anorectal malformations (ARMs) are birth defects in which the rectum is malformed. ARMs are a spectrum of different congenital anomalies which vary from fairly minor lesions to complex anomalies. The cause of ARMs is unknown; the genetic basis of these anomalies is very complex because of their anatomical variability. In 8% of patients, genetic factors are clearly associated with ARMs. Anorectal malformation in Currarino syndrome represents the only association for which the gene HLXB9 has been identified.

The VACTERL association refers to a recognized group of birth defects which tend to co-occur. This pattern is a recognized association, as opposed to a syndrome, because there is no known pathogenetic cause to explain the grouped incidence.

Duodenal atresia is the congenital absence or complete closure of a portion of the lumen of the duodenum. It causes increased levels of amniotic fluid during pregnancy (polyhydramnios) and intestinal obstruction in newborn babies. Newborns present with bilious or non-bilous vomiting within the first 24 to 48 hours after birth, typically after their first oral feeding. Radiography shows a distended stomach and distended duodenum, which are separated by the pyloric valve, a finding described as the double-bubble sign.

The tracheoesophageal septum is an embryological structure. It is formed from the tracheoesophageal folds or ridges which fuse in the midline. It divides the oesophagus from the trachea during prenatal development. Developmental abnormalities can lead to a tracheoesophageal fistula.

A tracheo-esophageal puncture is a surgically created hole between the trachea (windpipe) and the esophagus in a person who has had a total laryngectomy, a surgery where the larynx is removed. The purpose of the puncture is to restore a person’s ability to speak after the vocal cords have been removed. This involves creation of a fistula between trachea and oesophagus, puncturing the short segment of tissue or “common wall” that typically separates these two structures. A voice prosthesis is inserted into this puncture. The prosthesis keeps food out of the trachea but lets air into the esophagus for oesophageal speech.

Bronchomalacia is a term for weak cartilage in the walls of the bronchial tubes, often occurring in children under a day. Bronchomalacia means 'floppiness' of some part of the bronchi. Patients present with noisy breathing and/or wheezing. There is collapse of a main stem bronchus on exhalation. If the trachea is also involved the term tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) is used. If only the upper airway the trachea is involved it is called tracheomalacia (TM). There are two types of bronchomalacia. Primary bronchomalacia is due to a deficiency in the cartilaginous rings. Secondary bronchomalacia may occur by extrinsic compression from an enlarged vessel, a vascular ring or a bronchogenic cyst. Though uncommon, idiopathic tracheobronchomalacia has been described in older adults.

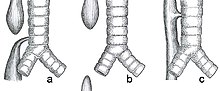

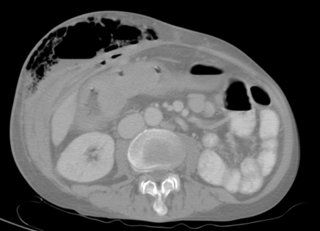

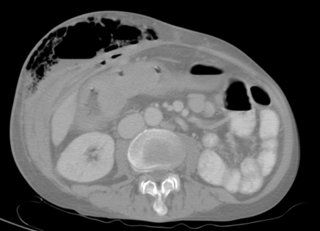

Double aortic arch is a relatively rare congenital cardiovascular malformation. DAA is an anomaly of the aortic arch in which two aortic arches form a complete vascular ring that can compress the trachea and/or esophagus. Most commonly there is a larger (dominant) right arch behind and a smaller (hypoplastic) left aortic arch in front of the trachea/esophagus. The two arches join to form the descending aorta which is usually on the left side. In some cases the end of the smaller left aortic arch closes and the vascular tissue becomes a fibrous cord. Although in these cases a complete ring of two patent aortic arches is not present, the term ‘vascular ring’ is the accepted generic term even in these anomalies.

A laryngeal cleft or laryngotracheoesophageal cleft is a rare congenital abnormality in the posterior laryngo-tracheal wall. It occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 to 20,000 births. It means there is a communication between the oesophagus and the trachea, which allows food or fluid to pass into the airway.

Tracheal agenesis is a rare birth defect with a prevalence of less than 1 in 50,000 in which the trachea fails to develop, resulting in an impaired communication between the larynx and the alveoli of the lungs. Although the defect is normally fatal, occasional cases have been reported of long-term survival following surgical intervention.

Mario Zaritzky is MD, scientist and inventor and currently lives and works as an associate professor of Radiology at Jackson Memorial Center. Previously, he was an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatric Radiology Department of Radiology, University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois, USA. Zaritzky coordinated the Argentine Network of Science in Midwestern, United States, from the Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation Programme of Argentina.

A urogenital fistula is an abnormal tract that exists between the urinary tract and bladder, ureters, or urethra. A urogenital fistula can occur between any of the organs and structures of the pelvic region. A fistula allows urine to continually exit through and out the urogenital tract. This can result in significant disability, interference with sexual activity, and other physical health issues, the effects of which may in turn have a negative impact on mental or emotional state, including an increase in social isolation. Urogenital fistulas vary in etiology. Fistulas are usually caused by injury or surgery, but they can also result from malignancy, infection, prolonged and obstructed labor and deliver in childbirth, hysterectomy, radiation therapy or inflammation. Of the fistulas that develop from difficult childbirth, 97 percent occur in developing countries. Congenital urogenital fistulas are rare; only ten cases have been documented. Abnormal passageways can also exist between the vagina and the organs of the gastrointestinal system, and these may also be termed fistulas.

Mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly syndrome, also known as growth delay-intellectual disability-mandibulofacial dysostosis-microcephaly-cleft palate syndrome, mandibulofacial dysostosis, guion-almeida type, or simply as MFDM syndrome is a rare genetic disorder which is characterized by developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, and craniofacial dysmorphisms.