Alaric I was the first king of the Visigoths, from 395 to 410. He rose to leadership of the Goths who came to occupy Moesia—territory acquired a couple of decades earlier by a combined force of Goths and Alans after the Battle of Adrianople.

Arcadius was Roman emperor from 383 to 408. He was the eldest son of the Augustus Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and the brother of Honorius. Arcadius ruled the eastern half of the empire from 395, when their father died, while Honorius ruled the west. A weak ruler, his reign was dominated by a series of powerful ministers and by his wife, Aelia Eudoxia.

Honorius was Roman emperor from 393 to 423. He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla. After the death of Theodosius, Honorius ruled the western half of the empire while his brother Arcadius ruled the eastern half. In 410, during Honorius's reign over the Western Roman Empire, Rome was sacked for the first time in almost 800 years.

Galla Placidia, daughter of the Roman emperor Theodosius I, was a mother, tutor, and advisor to emperor Valentinian III, and a major force in Roman politics for most of her life. She was queen consort to Ataulf, king of the Visigoths from 414 until his death in 415, briefly empress consort to Constantius III in 421, and managed the government administration as a regent during the early reign of Valentinian III, until her death.

The 400s decade ran from January 1, 400, to December 31, 409.

Year 408 (CDVIII) was a leap year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Bassus and Philippus. The denomination 408 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

The 390s decade ran from January 1, 390 to December 31, 399

Stilicho was a military commander in the Roman army who, for a time, became the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. He was of Vandal origins and married to Serena, the niece of emperor Theodosius I. He became guardian for the underage Honorius. After nine years of struggle against barbarian and Roman enemies, political and military disasters finally allowed his enemies in the court of Honorius to remove him from power. His fall culminated in his arrest and execution in 408.

Constantine III was a common Roman soldier who was declared emperor in Roman Britain in 407 and established himself in Gaul. He was co-emperor of the Roman Empire from 409 until 411.

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period from 395 to 476, where there were separate coequal courts dividing the governance of the empire in the Western and the Eastern provinces, with a distinct imperial succession in the separate courts. The terms Western Roman Empire and Eastern Roman Empire were coined in modern times to describe political entities that were de facto independent; contemporary Romans did not consider the Empire to have been split into two empires but viewed it as a single polity governed by two imperial courts as an administrative expediency. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in 476, and the Western imperial court in Ravenna was formally dissolved by Justinian in 554. The Eastern imperial court survived until 1453.

Constans II was caesar or heir apparent to his father Emperor Constantine III from 407 to 409 and co-emperor with Constantine and the Western Roman Emperor Honorius from 409 until his death. Constans was a monk prior to his father being acclaimed emperor by the army in Britain in early 407. Constans was summoned to the new imperial court, in Gaul, appointed to the position of Caesar and swiftly married so that a dynasty could be founded. In Hispania, Honorius's relatives rose in 408 and expelled Constantine's administration. An army under the generals Constans and Gerontius was sent to deal with this and Constantine's authority was re-established. Honorius acknowledged Constantine as co-emperor in early 409 and Constantine immediately raised Constans to the position of co-emperor, theoretically equal in rank to Honorius as well as to Constantine. Later in 409 Gerontius rebelled, proclaimed his client Maximus emperor and incited barbarian groups in Gaul to rise up. Constans was sent to quash the revolt, but was defeated and withdrew to Arles. In 410, Constans was sent to Hispania again. Gerontius had strengthened his army with barbarians and defeated Constans; the latter withdrew north and was defeated again and killed at Vienne early in 411. Gerontius then besieged Constantine in Arles.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast territory was divided into several successor polities. The Roman Empire lost the strengths that had allowed it to exercise effective control over its Western provinces; modern historians posit factors including the effectiveness and numbers of the army, the health and numbers of the Roman population, the strength of the economy, the competence of the emperors, the internal struggles for power, the religious changes of the period, and the efficiency of the civil administration. Increasing pressure from invading barbarians outside Roman culture also contributed greatly to the collapse. Climatic changes and both endemic and epidemic disease drove many of these immediate factors. The reasons for the collapse are major subjects of the historiography of the ancient world and they inform much modern discourse on state failure.

Flavius Rufinus was a 4th-century East Roman statesman of Aquitanian extraction who served as Praetorian prefect of the East for the emperor Theodosius I, as well as for his son Arcadius, under whom Rufinus exercised significant influence in the state affairs.

The Valentinianic or Valentinian dynasty was a ruling house of five generations of dynasts, including five Roman emperors during Late Antiquity, lasting nearly a hundred years from the mid fourth to the mid fifth century. They succeeded the Constantinian dynasty and reigned over the Roman Empire from 364 to 392 and from 425 to 455, with an interregnum (392–423), during which the Theodosian dynasty ruled and eventually succeeded them. The Theodosians, who intermarried into the Valentinian house, ruled concurrently in the east after 379.

The Battle of Verona was fought in June 402 by Alaric's Visigoths and a Western Roman force led by Stilicho. Alaric was defeated and forced to withdraw from Italy.

The Battle of Pollentia was fought on 6 April 402 (Easter) between the Romans under Stilicho and the Visigoths under Alaric I, during the first Gothic invasion of Italy (401–403). The Romans were victorious, and forced Alaric to retreat, though he rallied to fight again in the next year in the Battle of Verona, where he was again defeated. After this, Alaric retreated from Italy, leaving the province in peace until his second invasion in 409, after Stilicho's death.

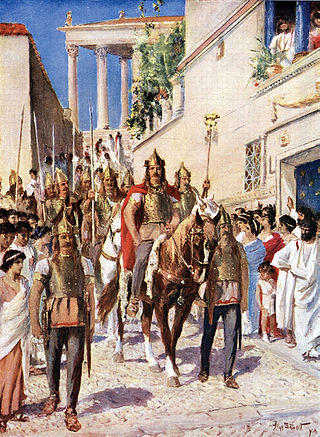

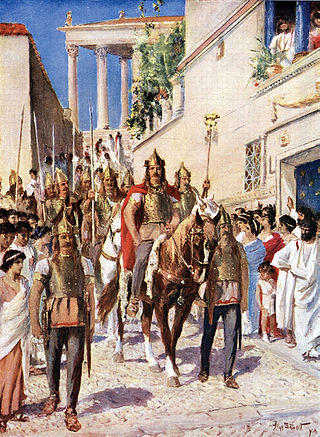

The Sack of Rome on 24 August 410 AD was undertaken by the Visigoths led by their king, Alaric. At that time, Rome was no longer the capital of the Western Roman Empire, having been replaced in that position first by Mediolanum in 286 and then by Ravenna in 402. Nevertheless, the city of Rome retained a paramount position as "the eternal city" and a spiritual center of the Empire. This was the first time in almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to a foreign enemy, and the sack was a major shock to contemporaries, friends and foes of the Empire alike.

Flavius Anthemius was a statesman of the Later Roman Empire. He is notable as a praetorian prefect of the East in the later reign of Arcadius and the first years of Theodosius II, during which time he led the government of the Eastern Roman Empire on behalf of the child emperor and supervised the construction of the first set of the Theodosian Walls.

Maria was the first Empress consort of Honorius, Western Roman Emperor. She was the daughter of the general Stilicho. Around 398 she married her first cousin, the Emperor Honorius. It is uncertain when she was born, but she was probably no older than fourteen at the time of her marriage. Maria had no children, and died in 407. After her death, Honorius married her sister, Thermantia.

Aemilia Materna Thermantia was the second Empress consort of Honorius, Western Roman Emperor.