The EVL Model involves two agents and their responses to a change initiated before the game began. The first agent is commonly referred to as the Citizen and the second is commonly referred to as the Government. EVL assumes that the change implemented before the game began was performed by the Government and negatively harms the Citizen.

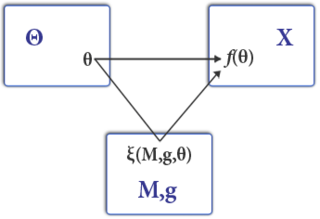

The formal definition of EVL is the following: [3]

There are two players:  . The

. The  moves first, and chooses among three actions

moves first, and chooses among three actions  . If the

. If the  chooses

chooses  , then

, then  can either

can either  or

or  . If the

. If the  chooses to

chooses to  , the

, the  then chooses between

then chooses between  or

or  . Subsequent to this (and any other action choices), the game terminates.

. Subsequent to this (and any other action choices), the game terminates.

Formally, this is represented by the set of histories  The terminal histories, upon reaching which the game terminates, is given by

The terminal histories, upon reaching which the game terminates, is given by  For all other histories, one of the two players makes a move, and this is given by the player function

For all other histories, one of the two players makes a move, and this is given by the player function

The utility function of the  is defined as

is defined as

In words, the

In words, the  incurs a cost of

incurs a cost of  whenever they choose to raise their

whenever they choose to raise their  , and if the

, and if the  , they get a payoff of

, they get a payoff of  . Irrespective of this choice, they can choose to

. Irrespective of this choice, they can choose to  for a payoff of

for a payoff of  or remain

or remain  for payoff of zero.

for payoff of zero.

Similarly, the payoff function of the  is defined as

is defined as  In words, the

In words, the  incurs a cost of one for

incurs a cost of one for  to the

to the  concerns, and gains a payoff of

concerns, and gains a payoff of  if the

if the  does not

does not  .

.

Theoretical Definition

The precursory policy that the Government has implemented has the effect of removing a benefit with the value of 1 from the Citizen and giving it to the Government. The value was chosen to be 1 so that all comparisons within the game can easily be converted to ratios and then adapted to other situations where the true value of the benefit is known.

In EVL, all possible actions that can be taken by the Citizen are grouped into one of three options. Exit options are those in which the Citizen accepts the loss of the benefit and instead alters their behavior to get the best possible alternative. Examples could include relocating assets to avoid a new tax, reincorporating a business to avoid new regulations, buying goods from a different store when the quality of the original diminishes, voting out the incumbent, etc. [1] The payoff of an Exit option for the Citizen is the variable E and the Government gets to keep the 1 it took initially. [1] [3]

Loyalty options are ones where the Citizen chooses to put up with the new policy and not alter their behavior. The payoff for the Citizen is 0 as they decide to take the loss and the Government receives the 1 it took plus the value of the Citizen's Loyalty. The value of the Citizen's Loyalty is the variable L. [1] [3]

Voice options are where the Citizen makes an active effort to show their dissatisfaction with the new policy and tries to get the Government to change its mind. Examples could be lobbying, protesting, petitioning, etc. [1] Voice options do not have immediate payoffs but are intended to give the Government a chance to Respond to the Citizen and revert the policy. In the event the Government does Respond, the payoff for the Citizen is the 1 the Government initially took minus the cost of using Voice. This cost is the variable c. If the Government chooses to Ignore then the Citizen can still Exit or remain Loyal. No matter what the Citizen chooses, they still have to bear the cost of using their Voice and so the payoff for Exit would be E - c and 0 - c for remaining Loyal. The Government would receive the payoff of L (the value of the Citizen's Loyalty) if they chose to Respond and revert the policy, 1 if they chose to Ignore and the Citizen Exits, and 1 + L if they Ignore and the Citizen chooses to remain Loyal. [1] [3]