Carl Edward Sagan was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by exposure to light. He assembled the first physical messages sent into space, the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, which were universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them. He argued in favor of the hypothesis, which has since been accepted, that the high surface temperatures of Venus are the result of the greenhouse effect.

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin controversia, as a composite of controversus – "turned in an opposite direction".

Peter H. Duesberg is a German-American molecular biologist and a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is known for his early research into the genetic aspects of cancer. He is a proponent of AIDS denialism, the claim that HIV does not cause AIDS.

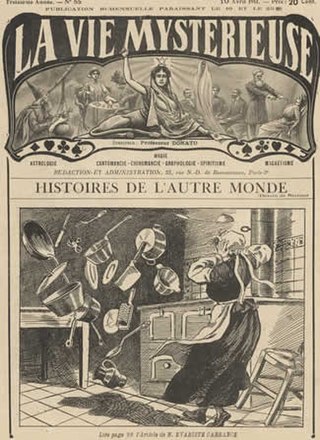

Parapsychology is the study of alleged psychic phenomena and other paranormal claims, for example, those related to near-death experiences, synchronicity, apparitional experiences, etc. Criticized as being a pseudoscience, the majority of mainstream scientists reject it. Parapsychology has also been criticised by mainstream critics for claims by many of its practitioners that their studies are plausible despite a lack of convincing evidence after more than a century of research for the existence of any psychic phenomena.

Broca's area, or the Broca area, is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

Lynn Margulis was an American evolutionary biologist, and was the primary modern proponent for the significance of symbiosis in evolution. Historian Jan Sapp has said that "Lynn Margulis's name is as synonymous with symbiosis as Charles Darwin's is with evolution." In particular, Margulis transformed and fundamentally framed current understanding of the evolution of cells with nuclei – an event Ernst Mayr called "perhaps the most important and dramatic event in the history of life" – by proposing it to have been the result of symbiotic mergers of bacteria. In 2002, Discover magazine recognized Margulis as one of the 50 most important women in science.

Pierre Paul Broca was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is involved with language. His work revealed that the brains of patients with aphasia contained lesions in a particular part of the cortex, in the left frontal region. This was the first anatomical proof of localization of brain function.

The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), formerly known as the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), is a program within the U.S. non-profit organization Center for Inquiry (CFI), which seeks to "promote scientific inquiry, critical investigation, and the use of reason in examining controversial and extraordinary claims." Paul Kurtz proposed the establishment of CSICOP in 1976 as an independent non-profit organization, to counter what he regarded as an uncritical acceptance of, and support for, paranormal claims by both the media and society in general. Its philosophical position is one of scientific skepticism. CSI's fellows have included notable scientists, Nobel laureates, philosophers, psychologists, educators, and authors. It is headquartered in Amherst, New York.

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Notable paranormal beliefs include those that pertain to extrasensory perception, spiritualism and the pseudosciences of ghost hunting, cryptozoology, and ufology.

Skeptical Inquirer is a bimonthly American general-audience magazine published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) with the subtitle: The Magazine for Science and Reason.

HIV/AIDS denialism is the belief, despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) does not cause acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Some of its proponents reject the existence of HIV, while others accept that HIV exists but argue that it is a harmless passenger virus and not the cause of AIDS. Insofar as they acknowledge AIDS as a real disease, they attribute it to some combination of sexual behavior, recreational drugs, malnutrition, poor sanitation, haemophilia, or the effects of the medications used to treat HIV infection (antiretrovirals).

Philip Hauge Abelson was an American physicist, scientific editor and science writer. Trained as a nuclear physicist, he co-discovered the element neptunium, worked on isotope separation in the Manhattan Project, and wrote the first study of nuclear marine propulsion for submarines. He later worked on a broad range of scientific topics and related public policy, including organic geochemistry, paleobiology and energy policy.

Probiotics are live microorganisms promoted with claims that they provide health benefits when consumed, generally by improving or restoring the gut microbiota. Probiotics are considered generally safe to consume, but may cause bacteria-host interactions and unwanted side effects in rare cases. There is some evidence that probiotics are beneficial for some conditions, but there is little evidence for many of the health benefits claimed for them.

Pseudoskepticism is a philosophical or scientific position that appears to be that of skepticism or scientific skepticism but in reality is a form of dogmatism.

Marcello Truzzi was an American sociologist and academic who was professor of sociology at New College of Florida and later at Eastern Michigan University, founding co-chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), a founder of the Society for Scientific Exploration, and director for the Center for Scientific Anomalies Research.

Zebra is the American medical slang for a surprising, often exotic, medical diagnosis, especially when a more commonplace explanation is more likely. It is shorthand for the aphorism coined in the late 1940s by Theodore Woodward, professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, who instructed his medical interns: "When you hear hoofbeats behind you, don't expect to see a zebra." By 1960, the aphorism was widely known in medical circles. The saying is a warning against the statistical base rate fallacy where the likelihood of something like a disease among the population is not taken into consideration for an individual.

The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis (YDIH) proposes that the onset of the Younger Dryas (YD) cool period (stadial) at the end of the Last Glacial Period, around 12,900 years ago was the result of some kind of extraterrestrial event with specific details varying between publications. The hypothesis is controversial and not widely accepted by relevant experts.

Evidence of absence is evidence of any kind that suggests something is missing or that it does not exist. What counts as evidence of absence has been a subject of debate between scientists and philosophers. It is often distinguished from absence of evidence.

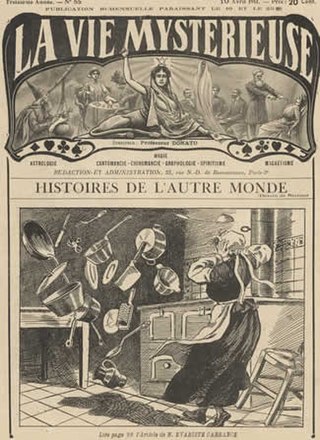

Telekinesis is a hypothetical psychic ability allowing an individual to influence a physical system without physical interaction. Experiments to prove the existence of telekinesis have historically been criticized for lack of proper controls and repeatability. There is no reliable evidence that telekinesis is a real phenomenon, and the topic is generally regarded as pseudoscience.

In philosophy, a razor is a principle or rule of thumb that allows one to eliminate unlikely explanations for a phenomenon, or avoid unnecessary actions.