Fakhr al-Mulk ibn Ammar was the last qadi of Tripoli, from 1099 to 1109, before the city was taken by the Crusaders.

Fakhr al-Mulk ibn Ammar was the last qadi of Tripoli, from 1099 to 1109, before the city was taken by the Crusaders.

Fakhr al-Mulk was a member of Banu Ammar. He succeeded his brother Jalal al-Mulk Ali ibn Muhammad during the First Crusade. At this point the Banu Ammar's territory spanned from Tartus and the fortresses of Arqa, and Khawabi, in addition to Tripoli, Byblos and Jableh. [1]

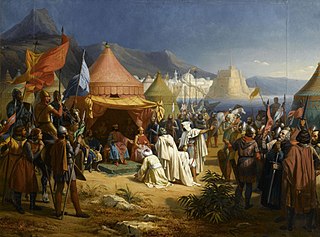

In 1099, the Crusaders crossed the country, in which Fakhr al-Mulk concluded an agreement with the envoys of the crusade, granting them the free passage of his state, and even providing them with supplies. However, the envoys dazzled by the riches of Tripoli, reported it to the Crusader leaders, arousing their covetousness. Raymond IV occupied Tartus and Maraclea and besieged Arqa, while Godfrey of Bouillon and Robert Curthose besieged Byblos.

On 9 March 1099, hoping to get Raymond to leave, Fakhr al-Mulk circulated the rumor of an imminent arrival of an Abbasid counter-crusade, but Raymond, far from giving in to panic, called other crusader leaders to his side. Upon their arrival in Arqa, the rumor was denied and Godfrey and Robert, furious at having had to abandon the siege of Byblos, decided to return to Jerusalem. However, Raymond insisted to continue the siege of Tripoli. When the Byzantines offered military aid to Raymond, he agreed to lift the siege on 13 May, as he did not want them to benefit from the conquests, then he negotiated with Fakhr al-Mulk. On 16 May 1099, the crusaders left Tripoli, and went to Beirut on 19 May. [2] Later on, Baldwin I who was heading towards Jerusalem was warned by Fakhr al-Mulk from an ambush near Byblos set by Shams al-Muluk Duqaq, Seljuk ruler of Damascus, when he arrived near Tripoli.

In August 1101, Fakhr al-Mulk captured Taj al-Muluk Buri who acted as a despotic governor of Jableh, yet he was treated well and sent back to Damascus, as he had previously suppressed a rebellion in Jableh two years earlier, which rebelled against Fakhr al-Mulk. [3]

Starting from 1102, Fakhr al-Mulk had to face the continuous attacks of the Crusaders under Raymond, in which he recaptured Tartus in April 1102, [4] and Byblos in April 1104. [5] After the Battle of Harran in 1104, Fakhr al-Mulk asked Sökmen, the former Ortoqid governor of Jerusalem, to intervene; Sökmen marched into Syria but was forced to return home. [6]

Fakhr al-Mulk then attacked Mons Peregrinus in September, 1104, killing many of the Franks and burning down one wing of the fortress. Raymond himself was badly wounded, and died five months later in February, 1105. He was replaced as leader by his nephew William II Jordan. On his deathbed, Raymond had reached an agreement with the qadi: if he would stop attacking the fortress, the crusaders would stop impeding Tripolitanian trade and merchandise. The qadi accepted.

In 1108, it became more and more difficult to bring food to the besieged by land. Many citizens sought to flee to Homs, Tyre, and Damascus. The nobles of the city, who had betrayed the city to the Franks by showing them how it was being resupplied with food, were executed in the crusader camp. [7] Fakhr al-Mulk, left to wait for help from the Seljuk sultan Mehmed I, went to Baghdad at the end of March with five hundred troops and many gifts. He passed through Damascus, now governed by Toghtekin after the death of Duqaq, and was welcomed with open arms. In Baghdad, the sultan received him with great spectacle, but had no time for Tripoli while there was a succession dispute in Mosul. Fakhr al-Mulk returned to Damascus in August, where he learned Tripoli had been handed over to Sharaf ad-Dawla ibn Abi al-Tayyib, [8] wali of al-Afdal Shahanshah, vizier of Egypt, by the nobles, who were tired of waiting for him to return. Eventually, Tripoli surrendered to the Crusaders, and Fakhr al-Mulk took refuge in Jableh. [9] In July 1109, the Crusaders under Tancred captured Jableh, [10] but he let Fakhr al-Mulk to leave freely.

Fakhr al-Mulk remained in the service of the Seljuks, and then entered the service of the atabeg Mawdud of Mosul, and finally of the Abbasid caliph al-Mustazhir. He died in 1118/9. [11] [12] [lower-alpha 1]

Year 1104 (MCIV) was a leap year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar.

Raymond of Saint-Gilles, also called Raymond IV of Toulouse or Raymond I of Tripoli, was the count of Toulouse, duke of Narbonne, and margrave of Provence from 1094, and one of the leaders of the First Crusade from 1096 to 1099. He spent the last five years of his life establishing the County of Tripoli in the Near East.

The Burid dynasty was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Oghuz Turkic origin which ruled over the Emirate of Damascus in the early 12th century, as subjects of the Seljuk Empire.

Abu Nasr Shams al-Muluk Duqaq was the Seljuq ruler of Damascus from 1095 to 1104.

Ridwan was a Seljuk emir of Aleppo from 1095 until his death.

Najm ad-Din Ilghazi ibn Artuq was the Turkoman Artukid ruler of Mardin from 1107 to 1122. He was born into the Oghuz tribe of Döğer.

Jableh is a Mediterranean coastal city in Syria, 25 km (16 mi) north of Baniyas and 25 km (16 mi) south of Latakia, with c. 80,000 inhabitants. As Ancient Gabala it was a Byzantine (arch)bishopric and remains a Latin Catholic titular see. It contains the tomb and mosque of Ibrahim Bin Adham, a legendary Sufi mystic who renounced his throne of Balkh and devoted himself to prayers for the rest of his life.

The siege of Tripoli lasted from 1102 until 12 July 1109. It took place on the site of the present day Lebanese city of Tripoli, in the aftermath of the First Crusade. It led to the establishment of the fourth crusader state, the County of Tripoli.

Zahir al-Din Toghtekin or Tughtekin, also spelled Tughtegin, was a Turkoman military leader, who was emir of Damascus from 1104 to 1128. He was the founder of the Burid dynasty of Damascus.

Taj al-Muluk Buri was an Turkoman atabeg of Damascus from 1128 to 1132. He was initially an officer in the army of Duqaq, the Seljuk ruler of Damascus, together with his father Toghtekin. When the latter took power after Duqaq's death, Buri acted as regent and later became atabeg himself. Damascus's Burid dynasty was named for him.

The First Crusade march down the Mediterranean coast, from recently taken Antioch to Jerusalem, started on 13 January 1099. During the march the Crusaders encountered little resistance, as local rulers preferred to make peace with them and furnish them with supplies rather than fight, with a notable exception of the aborted siege of Arqa. On 7 June, the Crusaders reached Jerusalem, which had been recaptured from the Seljuks by the Fatimids only the year before.

Sökmen was a Turkoman emir of the Seljuk Empire in the early 12th century.

Jalal al-Mulk Ali ibn Muhammad ibn Ammar was the ruler (qadi) of Tripoli during the First Crusade.

The Banu Munqidh, also referred to as the Munqidhites, were an Arab family that ruled an emirate in the Orontes Valley in northern Syria from the mid-11th century until the family's demise in an earthquake in 1157. The emirate was initially based in Kafartab before the Banu Munqidh took over the fortress of Shayzar in 1081 and made it their headquarters for the remainder of their rule. The capture of Shayzar was the culmination of a long, drawn-out process beginning with the Banu Munqidh's nominal assignment to the land by the Mirdasid emir of Aleppo in 1025, and accelerating with the weakened grip of Byzantine rule in northern Syria in the 1070s.

The siege of Aleppo by Baldwin II of Jerusalem and his allies lasted from 6 October 1124 to 25 January 1125. It ended in a Crusader withdrawal following the arrival of a relief force led by Aqsunqur al-Bursuqi.

Irtash was a Seljuk emir of Damascus in 1104. Irtash was born to Taj ad-Dawla Tutush, the brother of the Seljuk Sultan Malik-Shah I who established a principality in Syria after his brother gave the region and the adjacent areas to him. Following the death of Malik-Shah, Tutush claimed the Seljuk crown, but he was killed by the forces of his nephew Berkyaruq near Ray. Subsequently, Irtash's brother Ridwan moved to Aleppo and proclaimed himself the new emir. Irtash's other brother Duqaq's declaration of a new emirate in Damascus separated the Syrian Seljuk state into two and started a rivalry between the two brothers. Duqaq then imprisoned Irtash for nine years in Baalbek.

The Banu Ammar were a family of Shia Muslim magistrates (qadis) who ruled the city of Tripoli in what is now Lebanon from c.1065 until 1109.

The Banu Muhriz were an Arab princely family that controlled the fortresses of Marqab (Margat), Kahf and Qadmus in the late 11th and early 12th centuries.

Tutush Ibn Duqaq Ibn Tutush Seljuki, commonly known as Tutush II, was an infant Emir of Damascus.