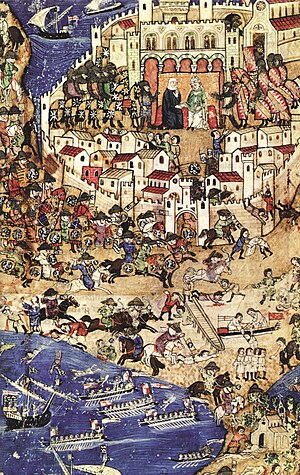

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see any significant fighting as Louis died of dysentery shortly after arriving on the shores of Tunisia. The Treaty of Tunis was negotiated between the Crusaders and the Hafsids. No changes in territory occurred, though there were commercial and some political rights granted to the Christians. The Crusaders withdrew back to Europe soon after.

The County of Tripoli (1102–1289) was one of the Crusader states. It was founded in the Levant in the modern-day region of Tripoli, northern Lebanon and parts of western Syria. When the Frankish Crusaders – mostly southern French forces – captured the region in 1109, Bertrand of Toulouse became the first count of Tripoli as a vassal of King Baldwin I of Jerusalem. From that time, the rule of the county was decided not strictly by inheritance but by factors such as military force, favour and negotiation. In 1289 the County of Tripoli fell to Sultan Qalawun of the Muslim Mamluks of Cairo. The county was absorbed into Mamluk Egypt.

Hugh III, also called Hugh of Antioch-Lusignan and the Great, was the king of Cyprus from 1267 and king of Jerusalem from 1268. Born into the family of the princes of Antioch, he effectively ruled as regent for underage kings Hugh II of Cyprus and Conrad III of Jerusalem for several years. Prevailing over the claims of his cousin Hugh of Brienne, he succeeded both young monarchs upon their deaths and appeared poised to be an effective political and military leader.

Bohemond VI, also known as the Fair, was the prince of Antioch and count of Tripoli from 1251 until his death. He ruled while Antioch was caught between the warring Mongol Empire and Mamluk Sultanate. He allied with the Mongols against the Muslim Mamluks and his Crusaders fought alongside the Mongols in their battles against the Mamluks. The Mamluks would achieve a historic victory against the Mongols and halt their advance westwards at the Battle of Ain Jalut. In 1268 Antioch was captured by the Mamluks under Baybars, and he was thenceforth a prince in exile. He was succeeded by his son, Bohemond VII.

Lord Edward's Crusade, sometimes called the Ninth Crusade, was a military expedition to the Holy Land under the command of Edward, Duke of Gascony in 1271–1272. It was an extension of the Eighth Crusade and was the last of the Crusades to reach the Holy Land before the fall of Acre in 1291 brought an end to the permanent crusader presence there.

The count of Tripoli was the ruler of the County of Tripoli, a crusader state from 1102 through to 1289. Of the four major crusader states in the Levant, Tripoli was created last.

Bohemond VII was the count of Tripoli and nominal prince of Antioch from 1275 to his death. The only part left of the Principality of Antioch was the port of Latakia. He spent much of his reign at war with the Templars (1277–1282).

Lucia was the last countess of Tripoli, a Crusader state in the Levant.

Qalāwūn aṣ-Ṣāliḥī was the seventh Turkic Bahri Mamluk Sultan of Egypt; he ruled from 1279 to 1290. He was called al-Manṣūr Qalāwūn. After having risen in power in the Mamluk court and elite circles, Qalawun eventually held the title of "the victorious king" and gained de facto authority over the sultanate. He is the founder of the Qalawunid dynasty that ruled Egypt for over a century.

Abaqa Khan, was the second Mongol ruler (Ilkhan) of the Ilkhanate. The son of Hulagu Khan and Lady Yesünčin and the grandson of Tolui, he reigned from 1265 to 1282 and was succeeded by his brother Ahmed Tekuder. Much of Abaqa's reign was consumed with civil wars in the Mongol Empire, such as those between the Ilkhanate and the northern khanate of the Golden Horde. Abaqa also engaged in unsuccessful attempts at invading Syria under the Mamluk Sultanate, which included the Second Battle of Homs.

Amalric, Lord of Tyre, also called Amalric of Lusignan or Amaury de Lusignan was a prince and statesman of the House of Lusignan, a younger son of King Hugh III of Cyprus and Isabella of the House of Ibelin. He was given the title of Lord of Tyre in 1291, shortly before the city of Tyre fell to the Mamluks of Egypt. He is often but incorrectly called the Prince of Tyre.

The siege of Acre took place in 1291 and resulted in the Crusaders' losing control of Acre to the Mamluks. It is considered one of the most important battles of the period. Although the crusading movement continued for several more centuries, the capture of the city marked the end of further crusades to the Levant. When Acre fell, the Crusaders lost their last major stronghold of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. They still maintained a fortress at the northern city of Tartus, engaged in some coastal raids, and attempted an incursion from the tiny island of Ruad; but, when they lost that, too, in a siege in 1302, the Crusaders no longer controlled any part of the Holy Land.

Sibylla of Armenia was the princess of Antioch and countess of Tripoli by marriage to Bohemond VI from 1254 to 1275, and then regent of the County of Tripoli until their son, Bohemond VII, came of age in 1277. She was closely allied with the bishop of Tortosa, Bartholomew Mansel, which frustrated the scheme to install her as ruler of Tripoli instead of her daughter Lucia after Bohemond VII's death in 1287. During her lifetime, both the principality and the county were lost to the Egyptian Mamluks.

Several attempts at a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Islamic caliphates, their common enemy, were made by various leaders among the Frankish Crusaders and the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. Such an alliance might have seemed an obvious choice: the Mongols were already sympathetic to Christianity, given the presence of many influential Nestorian Christians in the Mongol court. The Franks were open to the idea of support from the East, in part owing to the long-running legend of the mythical Prester John, an Eastern king in an Eastern kingdom who many believed would one day come to the assistance of the Crusaders in the Holy Land. The Franks and Mongols also shared a common enemy in the Muslims. However, despite many messages, gifts, and emissaries over the course of several decades, the often-proposed alliance never came to fruition.

The 1271 siege of Tripoli was initiated by the Mamluk ruler Baibars against the Frankish ruler of the Principality of Antioch and the County of Tripoli, Bohemond VI. It followed the dramatic fall of Antioch in 1268, and was an attempt by the Mamluks to completely destroy the Crusader states of Antioch and Tripoli.

The fall of Ruad in 1302 was one of the culminating events of the Crusades in the Eastern Mediterranean. In 1291, the Crusaders had lost their main power base at the coastal city of Acre, and the Muslim Mamluks had been systematically destroying the remaining Crusader ports and fortresses in the region, forcing the Crusaders to relocate the dwindling Kingdom of Jerusalem to the island of Cyprus. In 1299–1300, the Cypriots sought to retake the Syrian port city of Tortosa, by setting up a staging area on Ruad, two miles (3 km) off the coast of Tortosa. The plans were to coordinate an offensive between the forces of the Crusaders, and those of the Ilkhanate. However, though the Crusaders successfully established a bridgehead on the island, the Mongols did not arrive, and the Crusaders were forced to withdraw the bulk of their forces to Cyprus. The Knights Templar set up a permanent garrison on the island in 1300, but the Mamluks besieged and captured Ruad in 1302. With the loss of the island, the Crusaders lost their last foothold in the Holy Land and it marked the end of crusader presence in the Levant region.

Mongol Armenia or Ilkhanid Armenia refers to the period beginning in the early-to-mid 13th century during which both Zakarid Armenia and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia became tributary and vassal to the Mongol Empire and the successor Ilkhanate. Armenia and Cilicia remained under Mongol influence until around 1335.

Paul of Segni was an Italian nobleman and Franciscan friar who served as the bishop of Tripoli in the Levant from 1261 until 1285 and as a papal legate to the kingdoms of Germany and Sicily in 1279–1280. He was the most prominent churchman from the east at the Second Council of Lyon in 1274. After 1275, he was involved in a dispute with the bishop of Tortosa that took him to Rome. He spent his last five years in Italy.

Guy II or Guido II, surnamed Embriaco, was the lord of Gibelet from about 1271 until his death.

The fall of Outremer describes the history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from the end of the last European Crusade to the Holy Land in 1272 until the final loss in 1302. The kingdom was the center of Outremer—the four Crusader states—formed after the First Crusade in 1099 and reached its peak in 1187. The loss of Jerusalem in that year began the century-long decline. The years 1272–1302 are fraught with many conflicts throughout the Levant as well as the Mediterranean and Western European regions, and many Crusades were proposed to free the Holy Land from Mamluk control. The major players fighting the Muslims included the kings of England and France, the kingdoms of Cyprus and Sicily, the three Military Orders and Mongol Ilkhanate. Traditionally, the end of Western European presence in the Holy Land is identified as their defeat at the Siege of Acre in 1291, but the Christian forces managed to hold on to the small island fortress of Ruad until 1302.