The Benham class of ten destroyers was built for the United States Navy (USN). They were part of a series of USN destroyers limited to 1,500 tons standard displacement by the London Naval Treaty and built in the 1930s. The class was laid down in 1936-1937 and all were commissioned in 1939. Much of their design was based on the immediately preceding Gridley and Bagley-class destroyers. Like these classes, the Benhams were notable for including sixteen 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, the heaviest torpedo armament ever on US destroyers. They introduced a new high-pressure boiler that saved space and weight, as only three of the new boilers were required compared to four of the older designs. The class served extensively in World War II in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Pacific theaters, including Neutrality Patrols in the Atlantic 1940-1941. Sterett received the United States Presidential Unit Citation for the Battle of Guadalcanal and the Battle of Vella Gulf, and the Philippine Republic Presidential Unit Citation for her World War II service. Two of the class were lost during World War II, three were scrapped in 1947, while the remaining five ships were scuttled after being contaminated from the Operation Crossroads atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific.

The Clemson class was a series of 156 destroyers which served with the United States Navy from after World War I through World War II.

The Wickes-class destroyers were a class of 111 destroyers built by the United States Navy in 1917–19. Along with the 6 preceding Caldwell-class and 156 subsequent Clemson-class destroyers, they formed the "flush-deck" or "four-stack" type. Only a few were completed in time to serve in World War I, including USS Wickes, the lead ship of the class.

USS Farragut (DD-300) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

The Sims-class destroyers were built for the United States Navy, and commissioned in 1939 and 1940. These twelve ships were the last United States destroyer class completed prior to the American entry into World War II. All Sims-class ships saw action in World War II, and seven survived the war. No ship of this class saw service after 1946. They were built under the Second London Naval Treaty, in which the limit on destroyer standard displacement was lifted, but an overall limit remained. Thus, to maximize the number of destroyers and avoid developing an all-new design, the Sims class were only 70 tons larger as designed than previous destroyers. They are usually grouped with the 1500-ton classes and were the sixth destroyer class since production resumed with the Farragut class in 1932.

USS Converse (DD-291) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

USS Flusser (DD-289) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

USS Fuller (DD-297) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

USS Percival (DD-298) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

USS Paul Hamilton (DD-307) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

USS Zeilin (DD-313) was a Clemson-class destroyer in service with the United States Navy from 1920 to 1930. She was scrapped in 1930.

USS Mullany (DD-325) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

USS Preston (DD-327) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

USS Lamson (DD-328) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

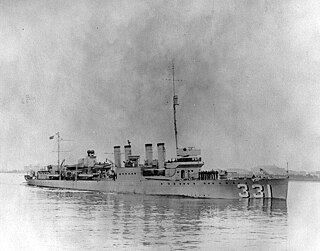

USS Macdonough (DD-331) was a Clemson-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War I.

The Porter-class destroyers were a class of eight 1,850-ton large destroyers in the United States Navy. Like the preceding Farragut-class, their construction was authorized by Congress on 26 April 1916, but funding was delayed considerably. They were designed based on a 1,850-ton standard displacement limit imposed by the London Naval Treaty; the treaty's tonnage limit allowed 13 ships of this size, and the similar Somers class was built later to meet the limit. The first four Porters were laid down in 1933 by New York Shipbuilding in Camden, New Jersey, and the next four in 1934 at Bethlehem Steel Corporation in Quincy, Massachusetts. All were commissioned in 1936 except Winslow, which was commissioned in 1937. They were built in response to the large Fubuki-class destroyers that the Imperial Japanese Navy was building at the time and were initially designated as flotilla leaders. They served extensively in World War II, in the Pacific War, the Atlantic, and in the Americas. Porter was the class' only loss, in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942.

The Gridley-class destroyers were a class of four 1500-ton destroyers in the United States Navy. They were part of a series of USN destroyers limited to 1,500 tons standard displacement by the London Naval Treaty and built in the 1930s. The first two ships were laid down on 3 June 1935 and commissioned in 1937. The second two were laid down in March 1936 and commissioned in 1938. Based on the preceding Mahan-class destroyers with somewhat different machinery, they had the same hull but had only a single stack and mounted sixteen 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, an increase of four. To compensate for the increased torpedo armament weight, the gun armament was slightly reduced from five 5"/38 caliber guns (127 mm) to four. USS Maury (DD-401) made the highest trial speed ever recorded for a United States Navy destroyer, 42.8 knots. All four ships served extensively in World War II, notably in the Solomon Islands and the Battle of the Philippine Sea, with Maury receiving a Presidential Unit Citation.

The Bagley class of eight destroyers was built for the United States Navy. They were part of a series of USN destroyers limited to 1,500 tons standard displacement by the London Naval Treaty and built in the 1930s. All eight ships were ordered and laid down in 1935 and subsequently completed in 1937. Their layout was based on the concurrently-built Gridley class destroyer design and was similar to the Benham class as well; all three classes were notable for including sixteen 21 inch torpedo tubes, the heaviest torpedo armament ever on US destroyers. They retained the fuel-efficient power plants of the Mahan-class destroyers, and thus had a slightly lower speed than the Gridleys. However, they had the extended range of the Mahans, 1,400 nautical miles (2,600 km) farther than the Gridleys. The Bagley class destroyers were readily distinguished visually by the prominent external trunking of the boiler uptakes around their single stack.

The Somers-class destroyer was a class of five 1850-ton United States Navy destroyers based on the Porter class. They were answers to the large destroyers that the Japanese navy was building at the time, and were initially intended to be flotilla leaders. They were laid down from 1935–1936 and commissioned from 1937–1939. They were built to round-out the thirteen destroyers of 1,850 tons standard displacement allowed by the tonnage limits of the London Naval Treaty, and were originally intended to be repeat Porters. However, new high-pressure, high-temperature boilers became available, allowing the use of a single stack. This combined with weight savings allowed an increase from two quadruple center-line torpedo tube mounts to three. However, the Somers class were still over-weight and top-heavy. This was the first US destroyer class to use 600 psi (4,100 kPa) steam superheated to 850 °F (454 °C), which became standard for US warships built in the late 1930s and World War II.

The Farragut-class destroyer was a group of 10 guided missile destroyers built for the United States Navy (USN) during the 1950s. They were the second destroyer class to be named for Admiral David Farragut. The class is sometimes referred to as the Coontz class, since Coontz was first to be designed and built as a guided missile ship, whereas the previous three ships were designed as all-gun units and converted later. The class was originally envisioned as a Destroyer Leader class, but was reclassified as Guided Missile Destroyers following the 1975 ship reclassification.