Christian mythology is the body of myths associated with Christianity. The term encompasses a broad variety of legends and narratives, especially those considered sacred narratives. Mythological themes and elements occur throughout Christian literature, including recurring myths such as ascending a mountain, the axis mundi, myths of combat, descent into the Underworld, accounts of a dying-and-rising god, a flood myth, stories about the founding of a tribe or city, and myths about great heroes of the past, paradises, and self-sacrifice.

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of the Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. According to legend, the various groups who were to become the Aztecs arrived from the north into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. The location of this valley and lake of destination is clear – it is the heart of modern Mexico City – but little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztec. There are different accounts of their origin. In the myth the ancestors of the Mexica/Aztec came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas to make the journey southward, hence their name "Azteca." Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, "the place of the seven caves", or at Tamoanchan.

Tezcatlipoca or Tezcatl Ipoca was a central deity in Aztec religion. He is associated with a variety of concepts, including the night sky, hurricanes, obsidian, and conflict. He was considered one of the four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, the primordial dual deity. His main festival was Toxcatl, which, like most religious festivals of Aztec culture, involved human sacrifice.

In Aztec mythology, Tecciztecatl was a lunar deity, representing the "Man in the Moon".

In Aztec mythology, Xolotl was a god of fire and lightning. He was commonly depicted as a dog-headed man and was a soul-guide for the dead. He was also god of twins, monsters, misfortune, sickness, and deformities. Xolotl is the canine brother and twin of Quetzalcoatl, the pair being sons of the virgin Chimalma. He is the dark personification of Venus, the evening star, and was associated with heavenly fire. The axolotl is named after him.

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

In Aztec mythology, Mētztli was a god or goddess of the moon, the night, and farmers. They were likely the same deity as Yohaulticetl or Coyolxauhqui and the male moon god Tecciztecatl; like the latter, who feared the Sun because of its fire.

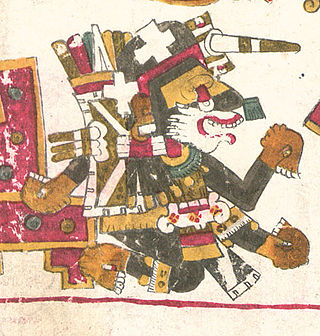

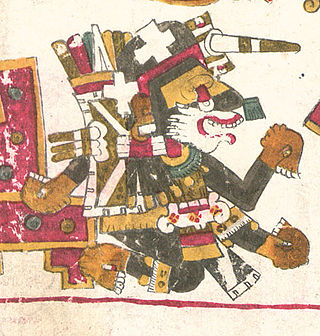

In Aztec mythology, the god Nanahuatzin or Nanahuatl, the most humble of the gods, sacrificed himself in fire so that he would continue to shine on Earth as the Sun, thus becoming the sun god. Nanahuatzin means "full of sores." According to a translation of the Histoyre du Mechique, Nanahuatzin is the son of Itzpapalotl and Cozcamiauh or Tonantzin, but was adopted by Piltzintecuhtli and Xōchiquetzal. In the Codex Borgia, Nanahuatzin is represented as a man emerging from a fire. This was originally interpreted as an illustration of cannibalism. He is probably an aspect of Xolotl.

The Hopi maintain a complex religious and mythological tradition stretching back over centuries. However, it is difficult to definitively state what all Hopis as a group believe. Like the oral traditions of many other societies, Hopi mythology is not always told consistently and each Hopi mesa, or even each village, may have its own version of a particular story, but "in essence the variants of the Hopi myth bear marked similarity to one another." It is also not clear that the stories told to non-Hopis, such as anthropologists and ethnographers, represent genuine Hopi beliefs or are merely stories told to the curious while keeping safe the more sacred Hopi teachings. As folklorist Harold Courlander states, "there is a Hopi reticence about discussing matters that could be considered ritual secrets or religion-oriented traditions."

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas comprise numerous different cultures. Each has its own mythologies, many of which share certain themes across cultural boundaries. In North American mythologies, common themes include a close relation to nature and animals as well as belief in a Great Spirit that is conceived of in various ways.

In Aztec mythology, the Centzonmīmixcōah are the gods of the northern stars. They are sons of Camaxtle-Mixcoatl with the Earth Goddess, according to the Codex Ramírez, or Tonatiuh with Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of the seas.

In creation myths, the term "Five Suns" refers to the belief of certain Nahua cultures and Aztec peoples that the world has gone through five distinct cycles of creation and destruction, with the current era being the fifth. It is primarily derived from a combination of myths, cosmologies, and eschatological beliefs that were originally held by pre-Columbian peoples in the Mesoamerican region, including central Mexico, and it is part of a larger mythology of Fifth World or Fifth Sun beliefs.

Mesoamerican creation myths are the collection of creation myths attributed to, or documented for, the various cultures and civilizations of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and Mesoamerican literature.

Snakes are a common occurrence in myths for a multitude of cultures. The Hopi people of North America viewed snakes as symbols of healing, transformation, and fertility. Snakes in Mexican folk culture tell about the fear of the snake to the pregnant women where the snake attacks the umbilical cord. The Great Goddess often had snakes as her familiars—sometimes twining around her sacred staff, as in ancient Crete—and they were worshipped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration. Although not entirely a snake, the plumed serpent, Quetzalcoatl, in Mesoamerican culture, particularly Mayan and Aztec, held a multitude of roles as a deity. He was viewed as a twin entity which embodied that of god and man and equally man and serpent, yet was closely associated with fertility. In ancient Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl was the son of the fertility earth goddess, Cihuacoatl, and cloud serpent and hunting god, Maxicoat. His roles took the form of everything from bringer of morning winds and bright daylight for healthy crops, to a sea god capable of bringing on great floods. As shown in the images there are images of the sky serpent with its tail in its mouth, it is believed to be a reverence to the sun, for which Quetzalcoatl was also closely linked.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

Spider Grandmother is an important figure in the mythology, oral traditions and folklore of many Native American cultures, especially in the Southwestern United States.

In Mesoamerican culture, Tonatiuh is an Aztec sun deity of the daytime sky who rules the cardinal direction of east. According to Aztec Mythology, Tonatiuh was known as "The Fifth Sun" and was given a calendar name of naui olin, which means "4 Movement". Represented as a fierce and warlike god, he is first seen in Early Postclassic art of the Pre-Columbian civilization known as the Toltec. Tonatiuh's symbolic association with the eagle alludes to the Aztec belief of his journey as the present sun, travelling across the sky each day, where he descended in the west and ascended in the east. It was thought that his journey was sustained by the daily sacrifice of humans. His Nahuatl name can also be translated to "He Who Goes Forth Shining" or "He Who Makes The Day." Tonatiuh was thought to be the central deity on the Aztec calendar stone but is no longer identified as such. In Toltec culture, Tonatiuh is often associated with Quetzalcoatl in his manifestation as the morning star aspect of the planet Venus.

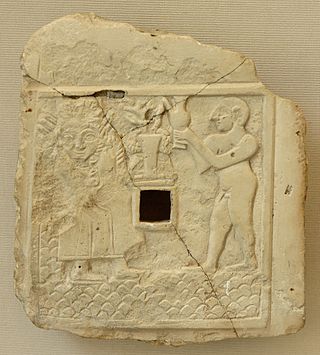

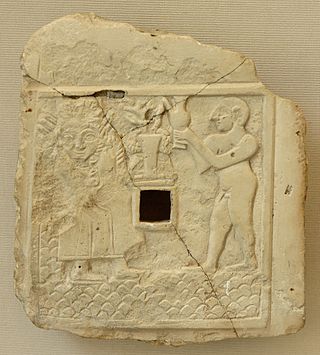

A vegetation deity is a nature deity whose disappearance and reappearance, or life, death and rebirth, embodies the growth cycle of plants. In nature worship, the deity can be a god or goddess with the ability to regenerate itself. A vegetation deity is often a fertility deity. The deity typically undergoes dismemberment, scattering, and reintegration, as narrated in a myth or reenacted by a religious ritual. The cyclical pattern is given theological significance on themes such as immortality, resurrection, and reincarnation. Vegetation myths have structural resemblances to certain creation myths in which parts of a primordial being's body generate aspects of the cosmos, such as the Norse myth of Ymir.

In Aztec mythology, Creator-gods are the only four Tezcatlipocas, the children of the creator couple Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl "Lord and Lady of Duality", "Lord and Lady of the Near and the Nigh", "Father and Mother of the Gods", "Father and Mother of us all", who received the gift of the ability to create other living beings without childbearing. They reside atop a mythical thirteenth heaven Ilhuicatl-Omeyocan "the place of duality".