Halibut is the common name for three flatfish in the genera Hippoglossus and Reinhardtius from the family of right-eye flounders and, in some regions, and less commonly, other species of large flatfish.

A fisherman or fisher is someone who captures fish and other animals from a body of water, or gathers shellfish.

Trawling is an industrial method of fishing that involves pulling a fishing net, that is heavily weighted to keep it on the seafloor, through the water behind one or more boats. The net used for trawling is called a trawl. This principle requires netting bags which are towed through water to catch different species of fishes or sometimes targeted species. Trawls are often called towed gear or dragged gear.

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally, resulting in the species becoming increasingly underpopulated in that area. Overfishing can occur in water bodies of any sizes, such as ponds, wetlands, rivers, lakes or oceans, and can result in resource depletion, reduced biological growth rates and low biomass levels. Sustained overfishing can lead to critical depensation, where the fish population is no longer able to sustain itself. Some forms of overfishing, such as the overfishing of sharks, has led to the upset of entire marine ecosystems. Types of overfishing include: growth overfishing, recruitment overfishing, ecosystem overfishing.

A conventional idea of a sustainable fishery is that it is one that is harvested at a sustainable rate, where the fish population does not decline over time because of fishing practices. Sustainability in fisheries combines theoretical disciplines, such as the population dynamics of fisheries, with practical strategies, such as avoiding overfishing through techniques such as individual fishing quotas, curtailing destructive and illegal fishing practices by lobbying for appropriate law and policy, setting up protected areas, restoring collapsed fisheries, incorporating all externalities involved in harvesting marine ecosystems into fishery economics, educating stakeholders and the wider public, and developing independent certification programs.

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity that takes, cultures, processes, preserves, stores, transports, markets or sells fish or fish products. It is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization as including recreational, subsistence and commercial fishing, as well as the related harvesting, processing, and marketing sectors. The commercial activity is aimed at the delivery of fish and other seafood products for human consumption or as input factors in other industrial processes. The livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends directly or indirectly on fisheries and aquaculture.

The goal of fisheries management is to produce sustainable biological, environmental and socioeconomic benefits from renewable aquatic resources. Wild fisheries are classified as renewable when the organisms of interest produce an annual biological surplus that with judicious management can be harvested without reducing future productivity. Fishery management employs activities that protect fishery resources so sustainable exploitation is possible, drawing on fisheries science and possibly including the precautionary principle.

The Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSFCMA), commonly referred to as the Magnuson–Stevens Act (MSA), is the legislation providing for the management of marine fisheries in U.S. waters. Originally enacted in 1976 to assert control of foreign fisheries that were operating within 200 nautical miles off the U.S. coast, the legislation has since been amended, in 1996 and 2007, to better address the twin problems of overfishing and overcapacity. These ecological and economic problems arose in the domestic fishing industry as it grew to fill the vacuum left by departing foreign fishing fleets.

In economics, a common-pool resource (CPR) is a type of good consisting of a natural or human-made resource system, whose size or characteristics makes it costly, but not impossible, to exclude potential beneficiaries from obtaining benefits from its use. Unlike pure public goods, common pool resources face problems of congestion or overuse, because they are subtractable. A common-pool resource typically consists of a core resource, which defines the stock variable, while providing a limited quantity of extractable fringe units, which defines the flow variable. While the core resource is to be protected or nurtured in order to allow for its continuous exploitation, the fringe units can be harvested or consumed.

The Pacific Whiting Conservation Cooperative (PWCC) is a harvest and research cooperative formed by three companies that participate in the catcher/processor sector of the Pacific whiting fishery – American Seafoods, Glacier Fish Company, and Trident Seafoods.

Individual fishing quotas (IFQs), also known as "individual transferable quotas" (ITQs), are one kind of catch share, a means by which many governments regulate fishing. The regulator sets a species-specific total allowable catch (TAC), typically by weight and for a given time period. A dedicated portion of the TAC, called quota shares, is then allocated to individuals. Quotas can typically be bought, sold and leased, a feature called transferability. As of 2008, 148 major fisheries around the world had adopted some variant of this approach, along with approximately 100 smaller fisheries in individual countries. Approximately 10% of the marine harvest was managed by ITQs as of 2008. The first countries to adopt individual fishing quotas were the Netherlands, Iceland and Canada in the late 1970s, and the most recent is the United States Scallop General Category IFQ Program in 2010. The first country to adopt individual transferable quotas as a national policy was New Zealand in 1986.

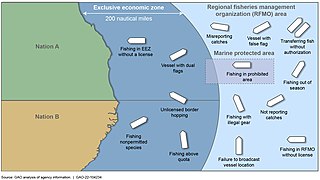

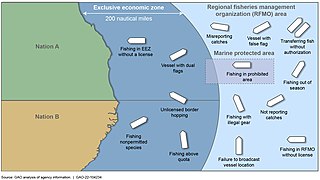

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) is an issue around the world. Fishing industry observers believe IUU occurs in most fisheries, and accounts for up to 30% of total catches in some important fisheries.

Canada's fishing industry is a key contributor to the success of the Canadian economy. In 2018, Canada's fishing industry was worth $36.1 billion in fish and seafood products and employed approximately 300,000 people. Aquaculture, which is the farming of fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants in fresh or salt water, is the fastest growing food production activity in the world and a growing sector in Canada. In 2015, aquaculture generated over $1 billion in GDP and close to $3 billion in total economic activity. The Department Of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) oversees the management of Canada's aquatic resources and works with fishermen across the country to ensure the sustainability of Canada's oceans and in-land fisheries.

This page is a list of fishing topics.

Until the 1960s, agriculture and fishing were the dominant industries of the economy of South Korea. The fishing industry of South Korea depends on the existing bodies of water that are shared between South Korea, China and Japan. Its coastline lies adjacent to the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea and the East Sea, and enables access to marine life such as fish and crustaceans.

As with other countries, the 200 nautical miles (370 km) exclusive economic zone (EEZ) off the coast of the United States gives its fishing industry special fishing rights. It covers 11.4 million square kilometres, which is the second largest zone in the world, exceeding the land area of the United States.

The coastline of the Russian Federation is the fourth longest in the world after the coastlines of Canada, Greenland, and Indonesia. The Russian fishing industry has an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 7.6 million km2 including access to twelve seas in three oceans, together with the landlocked Caspian Sea and more than two million rivers.

Catch share is a fishery management system that allocates a secure privilege to harvest a specific area or percentage of a fishery's total catch to individuals, communities, or associations. Examples of catch shares are individual transferable quota (ITQs), individual fishing quota (IFQs), territorial use rights for fishing (TURFs), limited access privileges (LAPs), sectors, and dedicated access privileges (DAPs).

A community-supported fishery (CSF) is an alternative business model for selling fresh, locally sourced seafood. CSF programs, modeled after increasingly popular community-supported agriculture programs, offer members weekly shares of fresh seafood for a pre-paid membership fee. The first CSF program was started in Port Clyde, Maine, in 2007, and similar CSF programs have since been started across the United States and in Europe. Community supported fisheries aim to promote a positive relationship between fishermen, consumers, and the ocean by providing high-quality, locally caught seafood to members. CSF programs began as a method to help marine ecosystems recover from the effects of overfishing while maintaining a thriving fishing community.

Sustainable sushi is sushi made from fished or farmed sources that can be maintained or whose future production does not significantly jeopardize the ecosystems from which it is acquired. Concerns over the sustainability of sushi ingredients arise from greater concerns over environmental, economic and social stability, and human health.