A drumlin, from the Irish word droimnín, first recorded in 1833, in the classical sense is an elongated hill in the shape of an inverted spoon or half-buried egg formed by glacial ice acting on underlying unconsolidated till or ground moraine. Assemblages of drumlins are referred to as fields or swarms; they can create a landscape which is often described as having a 'basket of eggs topography'.

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. The geological detritus originated from weathering and erosion of existing rocks, or from the solidification of molten lava blobs erupted by volcanoes. The geological detritus is transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice or mass movement, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

In structural geology, a fold is a stack of originally planar surfaces, such as sedimentary strata, that are bent or curved during permanent deformation. Folds in rocks vary in size from microscopic crinkles to mountain-sized folds. They occur as single isolated folds or in periodic sets. Synsedimentary folds are those formed during sedimentary deposition.

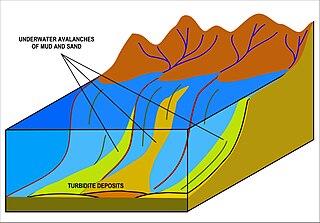

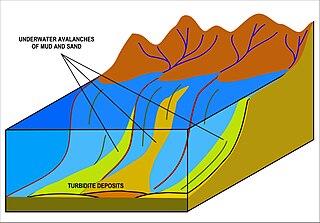

A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

A way up structure, way up criterion, or geopetal indicator is a characteristic relationship observed in a sedimentary or volcanic rock, or sequence of rocks, that makes it possible to determine whether they are the right way up or have been overturned by subsequent deformation. This technique is particularly important in areas affected by thrusting and where there is a lack of other indications of the relative ages of beds within the sequence, such as in the Precambrian where fossils are rare.

The Bouma sequence describes a classic set of sedimentary structures in turbidite beds deposited by turbidity currents at the bottoms of lakes, oceans and rivers.

The Roxbury Conglomerate, also informally known as Roxbury puddingstone, is a name for a rock formation that forms the bedrock underlying most of Roxbury, Massachusetts, now part of the city of Boston. The bedrock formation extends well beyond the limits of Roxbury, underlying part or all of Quincy, Canton, Milton, Dorchester, Dedham, Jamaica Plain, Brighton, Brookline, Newton, Needham, and Dover. It is named for exposures in Roxbury, Boston area.

A clastic dike is a seam of sedimentary material that fills an open fracture in and cuts across sedimentary rock strata or layering in other rock types. Clastic dikes form rapidly by fluidized injection or passively by water, wind, and gravity. Diagenesis may play a role in the formation of some dikes. Clastic dikes are commonly vertical or near-vertical. Centimeter-scale widths are common, but thicknesses range from millimetres to metres. Length is usually many times width.

Sedimentary structures include all kinds of features in sediments and sedimentary rocks, formed at the time of deposition.

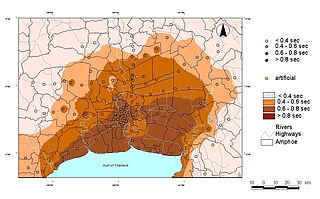

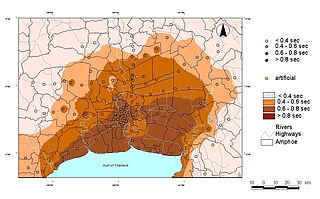

Seismic microzonation is defined as the process of subdividing a potential seismic or earthquake prone area into zones with respect to some geological and geophysical characteristics of the sites such as ground shaking, liquefaction susceptibility, landslide and rock fall hazard, earthquake-related flooding, so that seismic hazards at different locations within the area can correctly be identified. Microzonation provides the basis for site-specific risk analysis, which can assist in the mitigation of earthquake damage. In most general terms, seismic microzonation is the process of estimating the response of soil layers under earthquake excitations and thus the variation of earthquake characteristics on the ground surface.

Seismites are sedimentary beds and structures deformed by seismic shaking. The German paleontologist Adolf Seilacher first used the term in 1969 to describe earthquake-deformed layers. Today, the term is applied to both sedimentary layers and soft sediment deformation structures formed by shaking. This subtle change in usage accommodates structures that may not remain within a layer.

The Hebridean Terrane is one of the terranes that form part of the Caledonian orogenic belt in northwest Scotland. Its boundary with the neighbouring Northern Highland Terrane is formed by the Moine Thrust Belt. The basement is formed by Archaean and Paleoproterozoic gneisses of the Lewisian complex, unconformably overlain by the Neoproterozoic Torridonian sediments, which in turn are unconformably overlain by a sequence of Cambro–Ordovician sediments. It formed part of the Laurentian foreland during the Caledonian continental collision.

Load casts are bulges, lumps, and lobes that can form on the bedding planes that separate the layers of sedimentary rocks. The lumps "hang down" from the upper layer into the lower layer, and typically form with fairly equal spacing. These features form during soft-sediment deformation shortly after sediment burial, before the sediments lithify. They can be created when a denser layer of sediment is deposited on top of a less-dense sediment. This arrangement is gravitationally unstable, which encourages formation of a Rayleigh-Taylor instability if the sediment becomes liquefied. Once the sediments can flow, the instability creates the "hanging" lobes and knobs of the load casts as plumes of the denser sediment descend into the less-dense layer.

Ball-and-pillow structures are masses of clastic sediment that take the form of isolated pillows or protruding ball structures. These soft-sediment deformations are usually found at the base of sandstone beds that are interbedded with mudstone. It is also possible to find ball-and-pillows in limestone beds that overlie shale, but it's less common. They are normally hemispherical or kidney shaped, and range in size from a few inches to several feet.

Soft-sediment deformation structures develop at deposition or shortly after, during the first stages of the sediment's consolidation. This is because the sediments need to be "liquid-like" or unsolidified for the deformation to occur. These formations have also been put into a category called water-escape structures by Lowe (1975). The most common places for soft-sediment deformations to materialize are in deep water basins with turbidity currents, rivers, deltas, and shallow-marine areas with storm impacted conditions. This is because these environments have high deposition rates, which allows the sediments to pack loosely.

The Unkar Group is a sequence of strata of Proterozoic age that are subdivided into five geologic formations and exposed within the Grand Canyon, Arizona, Southwestern United States. The 5-unit Unkar Group is the basal member of the 8-member Grand Canyon Supergroup. The Unkar is about 1,600 to 2,200 m thick and composed, in ascending order, of the Bass Formation, Hakatai Shale, Shinumo Quartzite, Dox Formation, and Cardenas Basalt. Units 4 & 5 are found mostly in the eastern region of Grand Canyon. Units 1 through 3 are found in central Grand Canyon. The Unkar Group accumulated approximately between 1250 and 1104 Ma. In ascending order, the Unkar Group is overlain by the Nankoweap Formation, about 113 to 150 m thick; the Chuar Group, about 1,900 m (6,200 ft) thick; and the Sixtymile Formation, about 60 m (200 ft) thick. These are all of the units of the Grand Canyon Supergroup. The Unkar Group makes up approximately half of the thickness of the 8-unit Supergroup.

The Neoproterozoic Nankoweap Formation, is a thin sequence of distinctive red beds that consist of reddish brown and tan sandstones and subordinate siltstones and mudrocks that unconformably overlie basaltic lava flows of the Cardenas Basalt of the Unkar Group and underlie the sedimentary strata of the Galeros Formation of the Chuar Group. The Nankoweap Formation is slightly more than 100 m in thickness. It is informally subdivided into informal lower and upper members that are separated and enclosed by unconformities. Its lower (ferruginous) member is 0 to 15 m thick. The Grand Canyon Supergroup, of which the Nankoweap Formation is part, unconformably overlies deeply eroded granites, gneisses, pegmatites, and schists that comprise Vishnu Basement Rocks.

The Shinumo Quartzite also known as the Shinumo Sandstone, is a Mesoproterozoic rock formation, which outcrops in the eastern Grand Canyon, Coconino County, Arizona,. It is the 3rd member of the 5-unit Unkar Group. The Shinumo Quartzite consists of a series of massive, cliff-forming sandstones and sedimentary quartzites. Its cliffs contrast sharply with the stair-stepped topography of typically brightly-colored strata of the underlying slope-forming Hakatai Shale. Overlying the Shinumo, dark green to black, fissile, slope-forming shales of the Dox Formation create a well-defined notch. It and other formations of the Unkar Group occur as isolated fault-bound remnants along the main stem of the Colorado River and its tributaries in Grand Canyon.

Typically, the Shinumo Quartzite and associated strata of the Unkar Group dip northeast (10°–30°) toward normal faults that dip 60+° toward the southwest. This can be seen at the Palisades fault in the eastern part of the main Unkar Group outcrop area.

The Dox Formation, also known as the Dox Sandstone, is a Mesoproterozoic rock formation that outcrops in the eastern Grand Canyon, Coconino County, Arizona. The strata of the Dox Formation, except for some more resistant sandstone beds, are relatively susceptible to erosion and weathering. The lower member of the Dox Formation consists of silty-sandstone and sandstone, and some interbedded argillaceous beds, that form stair-stepped, cliff-slope topography. The bulk of the Dox Formation typically forms rounded and sloping hill topography that occupies an unusually broad section of the canyon.

Salt surface structures are extensions of salt tectonics that form at the Earth's surface when either diapirs or salt sheets pierce through the overlying strata. They can occur in any location where there are salt deposits, namely in cratonic basins, synrift basins, passive margins and collisional margins. These are environments where mass quantities of water collect and then evaporate; leaving behind salt and other evaporites to form sedimentary beds. When there is a difference in pressure, such as additional sediment in a particular area, the salt beds – due to the unique ability of salt to behave as a fluid under pressure – form into new structures. Sometimes, these new bodies form subhorizontal or moderately dipping structures over a younger stratigraphic unit, which are called allochthonous salt bodies or salt surface structures.