Related Research Articles

A glacier is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as crevasses and seracs, as it slowly flows and deforms under stresses induced by its weight. As it moves, it abrades rock and debris from its substrate to create landforms such as cirques, moraines, or fjords. Although a glacier may flow into a body of water, it forms only on land and is distinct from the much thinner sea ice and lake ice that form on the surface of bodies of water.

A drumlin, from the Irish word droimnín, first recorded in 1833, in the classical sense is an elongated hill in the shape of an inverted spoon or half-buried egg formed by glacial ice acting on underlying unconsolidated till or ground moraine. Assemblages of drumlins are referred to as fields or swarms; they can create a landscape which is often described as having a 'basket of eggs topography'.

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris, sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice sheet. It may consist of partly rounded particles ranging in size from boulders down to gravel and sand, in a groundmass of finely-divided clayey material sometimes called glacial flour. Lateral moraines are those formed at the side of the ice flow, and terminal moraines were formed at the foot, marking the maximum advance of the glacier. Other types of moraine include ground moraines and medial moraines.

Till or glacial till is unsorted glacial sediment.

Glaciology is the scientific study of glaciers, or more generally ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

A ridge is a long, narrow, elevated geomorphologic landform, structural feature, or combination of both separated from the surrounding terrain by steep sides. The sides of a ridge slope away from a narrow top, the crest or ridgecrest, with the terrain dropping down on either side. The crest, if narrow, is also called a ridgeline. Limitations on the dimensions of a ridge are lacking. Its height above the surrounding terrain can vary from less than a meter to hundreds of meters. A ridge can be either depositional, erosional, tectonic, or combination of these in origin and can consist of either bedrock, loose sediment, lava, or ice depending on its origin. A ridge can occur as either an isolated, independent feature or part of a larger geomorphological and/or structural feature. Frequently, a ridge can be further subdivided into smaller geomorphic or structural elements.

Glacial landforms are landforms created by the action of glaciers. Most of today's glacial landforms were created by the movement of large ice sheets during the Quaternary glaciations. Some areas, like Fennoscandia and the southern Andes, have extensive occurrences of glacial landforms; other areas, such as the Sahara, display rare and very old fossil glacial landforms.

The Oak Ridges Moraine is a geological landform that runs east-west across south central Ontario, Canada. It developed about 12,000 years ago, during the Wisconsin glaciation in North America. A complex ridge of sedimentary material, the moraine is known to have partially developed under water. The Niagara Escarpment played a key role in forming the moraine in that it acted as a dam for glacial meltwater trapped between it and two ice lobes.

In geology, a depression is a landform sunken or depressed below the surrounding area. Depressions form by various mechanisms.

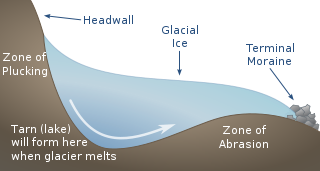

A terminal moraine, also called end moraine, is a type of moraine that forms at the terminal (edge) of a glacier, marking its maximum advance. At this point, debris that has accumulated by plucking and abrasion, has been pushed by the front edge of the ice, is driven no further and instead is deposited in an unsorted pile of sediment. Because the glacier acts very much like a conveyor belt, the longer it stays in one place, the greater the amount of material that will be deposited. The moraine is left as the marking point of the terminal extent of the ice.

Plucking, also referred to as quarrying, is a glacial phenomenon that is responsible for the weathering and erosion of pieces of bedrock, especially large "joint blocks". This occurs in a type of glacier called a "valley glacier". As a glacier moves down a valley, friction causes the basal ice of the glacier to melt and infiltrate joints (cracks) in the bedrock. The freezing and thawing action of the ice enlarges, widens, or causes further cracks in the bedrock as it changes volume across the ice/water phase transition, gradually loosening the rock between the joints. This produces large pieces of rock called joint blocks. Eventually these joint blocks come loose and become trapped in the glacier.

A tunnel valley is a U-shaped valley originally cut under the glacial ice near the margin of continental ice sheets such as that now covering Antarctica and formerly covering portions of all continents during past glacial ages. They can be as long as 100 km (62 mi), 4 km (2.5 mi) wide, and 400 m (1,300 ft) deep.

Glacial surges are short-lived events where a glacier can advance substantially, moving at velocities up to 100 times faster than normal. Surging glaciers cluster around a few areas. High concentrations of surging glaciers occur in the Karakoram, Pamir Mountains, Svalbard, the Canadian Arctic islands, Alaska and Iceland, although overall it is estimated that only one percent of all the world's glaciers ever surge. In some glaciers, surges can occur in fairly regular cycles, with 15 to 100 or more surge events per year. In other glaciers, surging remains unpredictable. In some glaciers, however, the period of stagnation and build-up between two surges typically lasts 10 to 200 years and is called the quiescent phase. During this period the velocities of the glacier are significantly lower, and the glaciers can retreat substantially.

Sole marks are sedimentary structures found on the bases of certain strata, that indicate small-scale grooves or irregularities. This usually occurs at the interface of two differing lithologies and/or grain sizes. They are commonly preserved as casts of these indents on the bottom of the overlying bed. This is similar to casts and molds in fossil preservation. Occurring as they do only at the bottom of beds, and their distinctive shapes, they can make useful way up structures and paleocurrent indicators.

U-shaped valleys, also called trough valleys or glacial troughs, are formed by the process of glaciation. They are characteristic of mountain glaciation in particular. They have a characteristic U shape in cross-section, with steep, straight sides and a flat or rounded bottom. Glaciated valleys are formed when a glacier travels across and down a slope, carving the valley by the action of scouring. When the ice recedes or thaws, the valley remains, often littered with small boulders that were transported within the ice, called glacial till or glacial erratic.

A subaqueous fan is a fan-shaped deposit formed beneath water, and are commonly related to glaciers and crater lakes.

Fluvioglacial landforms are those that result from the associated erosion and deposition of sediments caused by glacial meltwater. These landforms may also be referred to as glaciofluvial in nature. Glaciers contain suspended sediment loads, much of which is initially picked up from the underlying landmass. Landforms are shaped by glacial erosion through processes such as glacial quarrying, abrasion, and meltwater. Glacial meltwater contributes to the erosion of bedrock through both mechanical and chemical processes.

Glacial flutes, also known as glacial fluting, are low, narrow, elongate, straight, parallel ridges that range between several centimeters to a few meters both in width and height. This glacial landform generally consist of glacial till, but sometimes either sand or silt and clay. They form subglacially and are orientated parallel to the direction of glacier flow. They occur in parallel sets of ridges known as swarms. Because of their narrow width and low height, they are often hard to identify during ground or bottom surveys. As a result, they have to be mapped by high-resolution satellite data or LiDAR techniques on land and by high-resolution side-scan sonar at sea.

Parting lineation is a subtle sedimentary structure in which sand grains are aligned in parallel lines or grooves on the surface of a body of sand. The orientation of the lineation is used as a paleocurrent indicator, although the precise flow direction is often indeterminable. They are also the primary indicator of the lower part of the upper flow regime bedform.

The glacial series refers to a particular sequence of landforms in Central Europe that were formed during the Pleistocene glaciation beneath the ice sheets, along their margins and on their forelands during each glacial advance.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Neuendorf, K.K.E., J.P. Mehl, Jr., and J.A. Jackson, eds. (2005) Glossary of Geology (5th ed.). Alexandria, Virginia, American Geological Institute. 779 pp. ISBN 0-922152-76-4

- 1 2 Bell, T., Cooper, A.K., Solheim, A., Todd, B.J., Dowdeswell, J.A., and others, 2016. Glossary of glaciated continental margins and related geoscience methods. In: Dowdeswell, J.A., Canals, M., Jakobson, M., Todd, B.J., Dowdeswell, E.K. and Hogan, K.A., eds. Atlas of Submarine Glacial Landforms: Modern, Quaternary and Ancient. Geological Society, London, Memoirs, 46, 555–574.

- 1 2 Benn, D.I., and Evans, D.J.A., 2010. Glaciers and Glaciation. London, England, Hodder-Arnold. 816 pp. ISBN 978-0340905791

- ↑ Chamberlin, T.C., 1888. The Rock-scorings of the Great Ice Invasions, In J. W, Powell, 7th Annual Field Report 1885-6. United States Geological Survey, pp. 155-248.

- ↑ Collinson, J., and Mountney, N., 2019. Sedimentary Structures, 4th ed. Dunedin, England, Academic Press Ltd. 779 pp. ISBN 978-1780460628

- ↑ Crowell, J.C., 1955. Directional-current structures from the Prealpine Flysch, Switzerland.Geological Society of America Bulletin, 66(11), pp.1351-1384.