Related Research Articles

The Tiananmen Square protests, known in China as the June Fourth Incident were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China, lasting from 15 April to 4 June 1989. After weeks of unsuccessful attempts between the demonstrators and the Chinese government to find a peaceful resolution, the Chinese government declared martial law on the night of 3 June and deployed troops to occupy the square in what is referred to as the Tiananmen Square massacre. The events are sometimes called the '89 Democracy Movement, the Tiananmen Square Incident, or the Tiananmen uprising.

Zhao Ziyang was a Chinese politician. He was the third premier of the People's Republic of China from 1980 to 1987, vice chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1981 to 1982, and CCP general secretary from 1987 to 1989. He was in charge of the political reforms in China from 1986, but lost power in connection with the reformative neoauthoritarianism current and his support of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

The Monument to the People's Heroes is a ten-story obelisk that was erected as a national monument of China to the martyrs of revolutionary struggle during the 19th and 20th centuries. It is located in the southern part of Tiananmen Square in Beijing, in front of the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong. The obelisk monument was built in accordance with a resolution of the First Plenary Session of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference adopted on November 30, 1949, with construction lasting from August 1952 to May 1958. The architect of the monument was Liang Sicheng, with some elements designed by his wife, Lin Huiyin. The civil engineer, Chen Zhide (陈志德) was also instrumental in realizing the final product.

The Tank Man is the nickname given to an unidentified individual, presumed to be a Chinese man, who stood in front of a column of Type 59 tanks leaving Tiananmen Square in Beijing on June 5, 1989, the day after the Chinese government had massacred hundreds of protesters. As the lead tank maneuvered to pass by the man, he repeatedly shifted his position in order to obstruct the tank's attempted path around him. The incident was filmed and shared to a worldwide audience. Internationally, it is considered one of the most iconic images of all time. Inside China, the image and the accompanying events are subject to censorship.

Harrison Evans Salisbury, was an American journalist and the first regular New York Times correspondent in Moscow after World War II.

Chen Xitong was a member of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party and the Mayor of Beijing until he was removed from office on charges of corruption in 1995.

Xiong Yan is a Chinese-American human rights activist, military officer, and Protestant chaplain. He was a dissident involved in 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. Xiong Yan studied at Peking University Law School from 1986–1989. He came to the United States of America as a political refugee in 1992, and later became a chaplain in U.S. Army, serving in Iraq. Xiong Yan is the author of three books, and has earned six degrees. He ran for Congress in New York's 10th congressional district in 2022, and his campaign was reportedly attacked by agents of China's Ministry of State Security.

Tiananmen Square or Tian'anmen Square is a city square in the city center of Beijing, China, named after the eponymous Tiananmen located to its north, which separates it from the Forbidden City. The square contains the Monument to the People's Heroes, the Great Hall of the People, the National Museum of China, and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong. Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China in the square on October 1, 1949; the anniversary of this event is still observed there. The size of Tiananmen Square is 765 x 282 meters. It has great cultural significance as it was the site of several important events in Chinese history.

Yao Yilin was a Vice Premier of the People's Republic of China from 1979 to 1988, and the country's First Vice Premier from 1988 to 1993.

The 20th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre (20周年六四遊行) was a series of rallies that took place in late May to early June 2009 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, during which the Chinese government sent troops to suppress the pro-democracy movement. While the anniversary is remembered around the world; the event is heavily censored on Chinese soil, particularly in Mainland China. Events which mark it only take place in Hong Kong, and in Macao to a much lesser extent.

The 10th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre (10周年六四遊行) was a series of rallies – street marches, parades, and candlelight vigils – that took place in late May to early June 1999 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of 4 June 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. The anniversary of the event, during which the Chinese government sent troops to suppress pro-democracy movement and many people are thought to have perished, is remembered around the world in public open spaces and in front of many Chinese embassies in Western countries. On Chinese soil, any mention of the event is completely taboo in Mainland China; events which mark it only take place in Hong Kong, and in Macao to a much lesser extent.

The Critical Moment – Li Peng Diaries is a book issued in 2010 in the United States by West Point Publishing House, a small publisher established by Zheng Cunzhu, a former 1989 pro-democracy activist. The book contains entries from a diary believed to be written by the late former Chinese Premier, Li Peng, covering the events leading up to and shortly after the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre.

During the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in Beijing, the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) played a decisive role in enforcing martial law, using force to suppress the demonstrations in the city. The killings in Beijing continue to taint the legacies of the party elders, led by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, and weigh on the generation of leaders whose careers advanced as their more moderate colleagues were purged or sidelined at the time. Within China, the role of the military in 1989 remains a subject of private discussion within the ranks of the party leadership and PLA.

The Beijing Workers' Autonomous Federation (BWAF), or Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Union was the primary Chinese workers' organization calling for political change during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. The group was formed in the wake of mourning activities for former General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Hu Yaobang in April 1989. The BWAF denounced political corruption, presenting itself as an independent union capable of "supervising the Communist Party," unlike the Party-controlled All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU).

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were the first of their type shown in detail on Western television. The Chinese government's response was denounced across the world; a report by the U.S. State Department said: "Foreign governments have expressed near universal revulsion over the crackdown although a few exceptions have supported China's approaches. Negative reactions range from punitive measures by Western countries to private criticisms in the East." Specifically, it said: "China's credentials as a socialist reformer were being called into question not only by Western European communists but also by progressives in Eastern Europe and, to a lesser extent, the Soviet Union." Notably however, many Asian countries remained silent throughout the protests; the government of India responded to the massacre by ordering the state television to pare down the coverage to the barest minimum, so as not to jeopardize a thawing in relations with China, and to offer political empathy for the events. Criticism came from both Western and Eastern Europe, North America, Australia and some east Asian and Latin American countries. North Korea, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany, among others, supported the Chinese government and denounced the protests. Overseas Chinese students demonstrated in many cities in Europe, America, the Middle East, and Asia against the Chinese government.

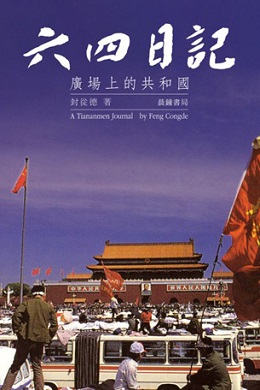

A Tiananmen Journal: Republic on the Square by Feng Congde (封从德) was first published in May 2009 in Hong Kong. This book records the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre from April 15, 1989, to June 4, 1989, in detail. Author Feng Congde is one of the student leader in the protest and his day-by- day diary entries, record every activity during the protest including the start of student protests in Peking University, the activities of major student leaders, important events, and unexposed stories about student organizations and their complex decision making.

The first of two student hunger strikes during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre began on May 13, 1989, in Beijing. The students said that they were willing to risk their lives to gain the government's attention. They believed that because plans were in place for the grand welcoming of Mikhail Gorbachev, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, on May 15, at Tiananmen Square, the government would respond. Although the students gained a dialogue session with the government on May 14, no rewards materialized. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) did not heed the students' demands and moved the welcome ceremony to the airport.

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre saw a massive redeployment of People's Liberation Army (PLA) troops into and around Beijing. After the declaration of martial law, the Central Military Commission (CMC) mobilized at least 22 divisions from 13 Armies, which converged on Beijing. This force far exceeded the local garrison, with troops being sent in from across China. Altogether, roughly 300,000 troops were involved in the campaign to quell the protests. By their end, the PLA had proven that it was largely willing to enforce party decrees with lethal force. Multiple significant breaches of military discipline occurred after the imposition of martial law. Some cases involved officers or entire units being unwilling to obey directives from farther up the chain of command, others related to the misuse of military equipment, and some were responsible for casualties incurred during the night of June 3. It is unclear when, how, or even if some PLA units received orders to open fire on the protesters, and so knowing whether or not an incident amounts to insubordination is difficult. If the PLA as a whole received orders to use lethal force, CMC chairman Deng Xiaoping must have given his assent to it. CMC vice-chairman and President Yang Shangkun's orders to the Central Military Commission on the 20th of May 1989 explicitly deny troops the authority to use lethal force during martial law, even when their lives are threatened by the protesters. According to Li Xinming's report to the politburo on June 19 however, 10 PLA soldiers did end up dying, along with 13 from the People's Armed Police. For these 23 dead, they inflicted 218 deaths on the protesters, although some sources place this number in the thousands.

During the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre student demonstrators created and distributed a large variety of propaganda. The first of these were memorial posters dedicated to Hu Yaobang, which were placed in Peking University following his death on Saturday April 15, 1989. On April 16 and 17, pamphlets, leaflets and other forms of propaganda began to be distributed by university students both in Peking University and at Tiananmen Square where large congregations of students began to form in what became the beginning stages of the protest. These were used to communicate among the students as well as to spread their messages and demands to groups such as the Chinese government and foreign media. Other forms of propaganda would emerge as the protests continued, such as a hunger strike beginning on May 13 and visits from celebrities and intellectuals, as well as speeches and songs. All of these were used to promote the interests of the student protest movement.

The four-day Sino-Soviet Summit was held in Beijing from 15-18 May 1989. This would be the first formal meeting between a Soviet Communist leader and a Chinese Communist leader since the Sino-Soviet split in the 1950s. The last Soviet leader to visit China was Nikita Khrushchev in September 1959. Both Deng Xiaoping, the paramount leader of China, and Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, proclaimed that the summit was the beginning of normalized state-to-state relations. The meeting between Mikhail Gorbachev and then General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Zhao Ziyang, was hailed as the "natural restoration" of party-to-party relations.

References

- ↑ 1. Nan Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen: Anatomy of the 1989 Mass Movement (Praeger Publishers, 1992), 144.

- ↑ 2. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 150.

- ↑ 3. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 143.

- ↑ 4. Michael Dobbs, "Protesters, and Reporters, Pedal to Beijing's Rally," The Washington Post, May 18, 1989, A36.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 6. Zhou He, Media and Tiananmen Square (Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 1996), 112.

- ↑ 6. Zhou He, Media and Tiananmen Square (Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 1996), 112.

- ↑ 6. Zhou He, Media and Tiananmen Square (Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 1996), 112.

- ↑ "Voice of America Beams TV Signals to China". The New York Times . 9 June 1989.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 7. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 149.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 8. "China expels two reporters as crackdown continues," The Ottawa Citizen, June 14, 1989, A1.

- ↑ 9. Jim Hoagland, "Blanket Television Coverage Gives Demonstrators a Media Security Blanket," The Washington Post, May 19, 1989, A35.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 10. He, Media and Tiananmen Square, 115.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 7. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 149.

- ↑ 11. "Troops march near Beijing square; foreign press coverage restricted," The Globe and Mail, June 2, 1989, A4.

- ↑ 5. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 148.

- ↑ 12. Jan Wong, "Tiananmen Square draws foreign tourists seeking radical chic," The Globe and Mail, May 31, 1989, A9.

- ↑ 7. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 149.

- ↑ 7. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 149.

- ↑ 11. "Troops march near Beijing square; foreign press coverage restricted," The Globe and Mail, June 2, 1989, A4.

- ↑ 13. Harrison E. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary: Thirteen Days in June (Little, Brown and Company, 1989), 16.

- ↑ 14. Frontline: The Tank Man, directed by Antony Thomas (April 11, 2006), DVD.

- ↑ 15. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary, 24.

- ↑ 16. "Chinese Army Detains Journals // CBS correspondent, cameraman missing in suppression of protests," Austin American-Statesman, June 4, 1989, A13.

- ↑ 17. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary, 64.

- ↑ 16. "Chinese Army Detains Journals // CBS correspondent, cameraman missing in suppression of protests," Austin American-Statesman, June 4, 1989, A13.

- ↑ 18. Johnathan Kaufman, "Canadian Reporter Thwarts Abduction Try," The Boston Globe, June 20, 1989.

- ↑ 19. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary, 62.

- ↑ 20. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary, 54.

- ↑ 11. "Troops march near Beijing square; foreign press coverage restricted," The Globe and Mail, June 2, 1989, A4.

- ↑ 21. Jonathan Mirsky, "Revenge of the old guard," The Observer, June 11, 1989.

- ↑ 7. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 149.

- ↑ 7. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 149.

- ↑ 7. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 149.

- ↑ 22. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary, 112.

- ↑ 22. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary, 112.

- ↑ 23. Salisbury, Tiananmen Diary, 111.

- ↑ Jay Mathews, "The Myth of Tiananmen and the Price of a Passive Press," Columbia Journalism Review September/October 1998

- ↑ Jay Mathews, "Back to School in Beijing," Washington Post August 13, 1989

- ↑ Jay Mathews, "The Myth of Tiananmen, And the Price of a Passive Press." Columbia Journalism Review Sept/Oct 1998

- ↑ 24. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 165.

- ↑ Lin, Chun (2006). The transformation of Chinese socialism. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-8223-3785-0. OCLC 63178961.

- ↑ 2. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 150.

- ↑ 24. Lin, Struggle for Tiananmen, 150.