The Nez Percé are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest a region for at least 11,500 years.

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger, was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) band of Nez Perce, a Native American tribe of the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States, in the latter half of the 19th century. He succeeded his father Tuekakas in the early 1870s.

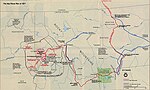

The Nez Perce War was an armed conflict that pitted several bands of the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans and their allies, a small band of the Palouse tribe led by Red Echo (Hahtalekin) and Bald Head, against the United States Army. The conflict, fought between June and October 1877, stemmed from the refusal of several bands of the Nez Perce, dubbed "non-treaty Indians," to give up their ancestral lands in the Pacific Northwest and move to an Indian reservation in Idaho. This forced removal was in violation of the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla, which granted the tribe 7.5 million acres of their ancestral lands and the right to hunt and fish on lands ceded to the U.S. government.

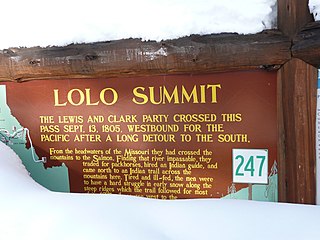

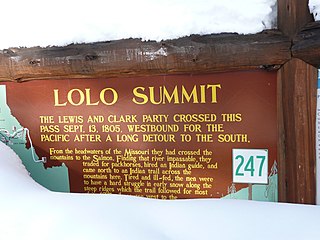

Lolo Pass, elevation 5,233 feet (1,595 m), is a mountain pass in the western United States, in the Bitterroot Range of the northern Rocky Mountains. It is on the border between the states of Montana and Idaho, approximately 40 miles (65 km) west-southwest of Missoula, Montana.

Clearwater National Forest with headquarters on the Nez Perce Reservation at Kamiah is located in North Central Idaho in the northwestern United States. The forest is bounded on the east by the state of Montana, on the north by the Idaho Panhandle National Forest, and on the south and west by the Nez Perce National Forest and Palouse Prairie.

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana, August 9–10, 1877, between the U.S. Army and the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans during the Nez Perce War. Both sides suffered heavy casualties. The Nez Perce withdrew in good order from the battlefield and continued their long fighting retreat that would result in their attempt to reach Canada and asylum.

The Battle of the Clearwater was a battle between the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph and the United States army. The army under General O. O. Howard surprised a Nez Perce village. The Nez Perce counter-attacked and inflicted significant casualties on the soldiers, but they were forced to abandon the village. After the battle, the Nez Perce retreated and crossed the Bitterroot Mountains via Lolo Pass with General Howard in pursuit.

The Battle of Bear Paw was the final engagement of the Nez Perce War of 1877. Following a 1,200-mile (1,900 km) running fight from western Idaho over the previous four months, the U.S. Army managed to corner most of the Nez Perce led by Chief Joseph in early October 1877 in northern Montana Territory, just 42 miles (68 km) south of the border with Canada, where the Nez Perce intended to seek refuge from persecution by the U.S. government.

The Bitterroot Valley is located in southwestern Montana, along the Bitterroot River between the Bitterroot Range and Sapphire Mountains, in the Northwestern United States.

The Battle of Camas Creek, August 20, 1877, was a raid by the Nez Perce Indians on a U.S. Army encampment and a subsequent battle during the Nez Perce War. The Nez Perce defeated three companies of U.S. cavalry and continued their fighting retreat to escape the U.S. Army.

Bitterroot National Forest comprises 1.587 million acres (6,423 km²) in west-central Montana and eastern Idaho, of the United States. It is located primarily in Ravalli County, Montana, but also has acreage in Idaho County, Idaho (29.24%), and Missoula County, Montana (0.49%).

The Battle of White Bird Canyon was fought on June 17, 1877 in Idaho Territory. White Bird Canyon was the opening battle of the Nez Perce War between the Nez Perce Indians and the United States. The battle was a significant defeat of the U.S. Army. It took place in the western part of present-day Idaho County, southwest of the city of Grangeville.

Looking Glass was a principal Nez Perce architect of many of the military strategies employed by the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War of 1877. He, along with Chief Joseph, directed the 1877 retreat from eastern Oregon into Montana and onward toward the Canada–US border during the Nez Perce War. He led the Alpowai band of the Nez Perce, which included the communities of Asotin, Alpowa, and Sapachesap along the Clearwater River in Idaho. He inherited his name from his father, the prominent Nez Percé chief Apash Wyakaikt or Ippakness Wayhayken and was therefore called by the whites Looking Glass.

The Battle of Canyon Creek was a military engagement between the Nez Perce Indians and the United States 7th Cavalry. The battle was part of the larger Indian Wars of the latter 19th century and the immediate Nez Perce War. It took place on September 13, 1877, west of present-day Billings, Montana in the canyons and benches around Canyon Creek.

Fort Missoula was established by the United States Army in 1877 on land that is now part of the city of Missoula, Montana, to protect settlers in Western Montana from possible threats from the Native American Indians, such as the Nez Perce.

U.S. Route 12 is a federal highway in north central Idaho. It extends 174.210 miles (280.364 km) from the Washington state line in Lewiston east to the Montana state line at Lolo Pass, generally along the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and is known as the Northwest Passage Scenic Byway It was previously known as the Lewis and Clark Highway.

Ollokot,, was a war leader of the Wallowa band of Nez Perce Indians and a leader of the young warriors in the Nez Perce War in 1877.

Toohoolhoolzote was a Nez Perce leader who fought in the Nez Perce War, after first advocating peace, and died at the Battle of Bear Paw.

The Battle of Cottonwood was a series of engagements July 3–5, 1877 in the Nez Perce War between the Native American Nez Perce people, and U.S. Army soldiers and civilian volunteers. Near Cottonwood, Idaho the Nez Perce, led by Chief Joseph, brushed aside the soldiers and continued their 1,170 miles (1,880 km) fighting retreat to cross the Rocky Mountains in an attempt to reach safety in Canada.

The Nez Perce in Yellowstone Park was the flight of the Nez Perce Indians through Yellowstone National Park between August 20 and Sept 7, during the Nez Perce War in 1877. As the U.S. army pursued the Nez Perce through the park, a number of hostile and sometimes deadly encounters between park visitors and the Indians occurred. Eventually, the army's pursuit forced the Nez Perce off the Yellowstone plateau and into forces arrayed to capture or destroy them when they emerged from the mountains of Yellowstone onto the valley of Clark's Fork of the Yellowstone River.