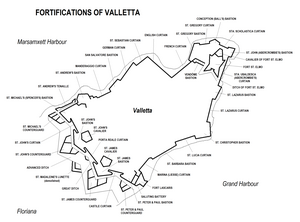

Valletta is the capital city of Malta and one of its 68 council areas. Located between the Grand Harbour to the east and Marsamxett Harbour to the west, its population as of 2021 was 5,157. As Malta’s capital city, it is a commercial centre for shopping, bars, dining, and café life. It is also the southernmost capital of Europe, and at just 0.61 square kilometres (0.24 sq mi), it is the European Union's smallest capital city.

City Gate is a gate located at the entrance of Valletta, Malta. The present gate, which is the fifth one to have stood on the site, was built between 2011 and 2014 to designs of the Italian architect Renzo Piano.

Fort Ricasoli is a bastioned fort in Kalkara, Malta, which was built by the Order of Saint John between 1670 and 1698. The fort occupies a promontory known as Gallows' Point and the north shore of Rinella Bay, commanding the entrance to the Grand Harbour along with Fort Saint Elmo. It is the largest fort in Malta and it has been on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1998, as part of the Knights' Fortifications around the Harbours of Malta.

Fort Manoel is a star fort on Manoel Island in Gżira, Malta. It was built in the 18th century by the Order of Saint John, during the reign of Grand Master António Manoel de Vilhena, after whom it is named. Fort Manoel is located to the north west of Valletta, and commands Marsamxett Harbour and the anchorage of Sliema Creek. The fort is an example of Baroque architecture, and it was designed with both functionality and aesthetics in mind.

Fort Saint Elmo is a star fort in Valletta, Malta. It stands on the seaward shore of the Sciberras Peninsula that divides Marsamxett Harbour from Grand Harbour, and commands the entrances to both harbours along with Fort Tigné and Fort Ricasoli. It is best known for its role in the Great Siege of Malta in 1565.

Saint Agatha's Tower, also known as the Red Tower, Mellieħa Tower or Fort Saint Agatha, is a large bastioned watchtower in Mellieħa, Malta. It was built between 1647 and 1649, as the sixth of the Lascaris towers. The tower's design is completely different from the rest of the Lascaris towers, but it is similar to the earlier Wignacourt towers. St. Agatha's Tower was the last large bastioned tower to be built in Malta.

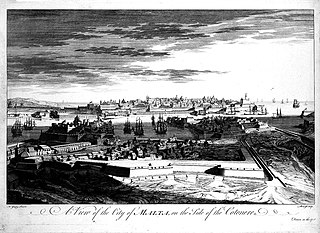

The Cottonera Lines, also known as the Valperga Lines, are a line of fortifications in Bormla and Birgu, Malta. They were built in the 17th and 18th centuries on higher ground and further outwards than the earlier line of fortifications, known as the Santa Margherita or Firenzuola lines, which also surround Bormla.

The Floriana Lines are a line of fortifications in Floriana, Malta, which surround the fortifications of Valletta and form the capital city's outer defences. Construction of the lines began in 1636 and they were named after the military engineer who designed them, Pietro Paolo Floriani. The Floriana Lines were modified throughout the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, and they saw use during the French blockade of 1798–1800. Today, the fortifications are still largely intact but rather dilapidated and in need of restoration.

The Citadel, also known as the Castello, is the citadel of Victoria on the island of Gozo, Malta. The area has been inhabited since the Bronze Age, and the site now occupied by the Cittadella is believed to have been the acropolis of the Punic-Roman city of Gaulos or Glauconis Civitas.

Fort Chambray or Fort Chambrai is a bastioned fort located in the precincts of Għajnsielem, on the island of Gozo, Malta. It was built in the mid-18th century by the Order of Saint John, in an area known as Ras it-Tafal, between the port of Mġarr and Xatt l-Aħmar. The fort was meant to be the citadel of a new city which was to replace the Cittadella as the island's capital, but this plan never materialized.

Lascaris Battery, also known as Fort Lascaris or Lascaris Bastion, is an artillery battery located on the east side of Valletta, Malta. The battery was built by the British in 1854, and it is connected to the earlier St. Peter & Paul Bastion of the Valletta Land Front. In World War II, the Lascaris War Rooms were dug close to the battery, and they served as Britain's secret headquarters for the defence of the island.

Saint John's Cavalier is a 16th-century cavalier in Valletta, Malta, which was built by the Order of St. John. It overlooks St. John's Bastion, a large obtuse-angled bastion forming part of the Valletta Land Front. St. John was one of nine planned cavaliers in the city, although eventually only two were built, the other one being the identical Saint James Cavalier. It was designed by the Italian military engineer Francesco Laparelli, while its construction was overseen by his Maltese assistant Girolamo Cassar.

The fortifications of Malta consist of a number of walled cities, citadels, forts, towers, batteries, redoubts, entrenchments and pillboxes. The fortifications were built over hundreds of years, from around 1450 BC to the mid-20th century, and they are a result of the Maltese islands' strategic position and natural harbours, which have made them very desirable for various powers.

The Santa Margherita Lines, also known as the Firenzuola Lines, are a line of fortifications in Cospicua, Malta. They were built in the 17th and 18th centuries to protect the land front defences of the cities of Birgu and Senglea. A second line of fortifications, known as the Cottonera Lines, was later built around the Santa Margherita Lines, while the city of Cospicua was founded in the 18th century within the Santa Margherita and Cottonera Lines.

The fortifications of Mdina are a series of defensive walls which surround the former capital city of Mdina, Malta. The city was founded as Maleth by the Phoenicians in around the 8th century BC, and it later became part of the Roman Empire under the name Melite. The ancient city was surrounded by walls, but very few remains of these have survived.

The fortifications of Birgu are a series of defensive walls and other fortifications which surround the city of Birgu, Malta. The first fortification to be built was Fort Saint Angelo in the Middle Ages, and the majority of the fortifications were built between the 16th and 18th centuries by the Order of Saint John. Most of the fortifications remain largely intact today.

The fortifications of Senglea are a series of defensive walls and other fortifications which surround the city of Senglea, Malta. The first fortification to be built was Fort Saint Michael in 1552, and the majority of the fortifications were built over the next decade when it was founded by Grand Master Claude de la Sengle. Modifications continued until the 18th century, but large parts of the fortifications were demolished between the 19th and 20th centuries. Today, all that remain of Senglea's fortifications are the seaward bastions and part of the land front.

Carlos de Grunenbergh, also known as Carlo Grunenberg, was a Flemish architect and military engineer active in the late 17th century. He mainly designed fortifications in Sicily and Malta. He was also a member of the Order of Saint John.

On 18 July 1806, approximately 40,000 lb (18,000 kg) of gunpowder stored in a magazine (polverista) in Birgu, Malta, accidentally detonated. The explosion killed approximately 200 people, including British and Maltese military personnel, and Maltese civilians from Birgu. Parts of the city's fortifications, some naval stores, and many houses were destroyed. The accident was found to be the result of negligence while transferring shells from the magazine.

The Chapel of St Anne is a Roman Catholic chapel located in Fort Saint Elmo in Valletta, Malta. Its existence was first documented in the late 15th century, and it was incorporated into the fort when the latter was constructed by the Order of St John in the mid-16th century. The chapel's present state dates back to the mid-17th century.