Related Research Articles

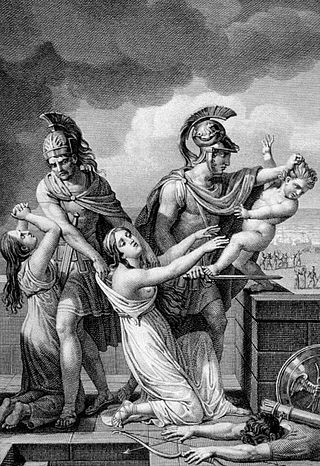

In Greek mythology, Astyanax was the son of Hector, the crown prince of Troy, and his wife, Princess Andromache of Cilician Thebe. His birth name was Scamandrius, but the people of Troy nicknamed him Astyanax, because he was the son of the city's great defender and the heir apparent's firstborn son.

Joachim du Bellay was a French poet, critic, and a founder of La Pléiade. He notably wrote the manifesto of the group: Défense et illustration de la langue française, which aimed at promoting French as an artistic language, equal to Greek and Latin.

Pierre de Ronsard was a French poet or, as his own generation in France called him, a "prince of poets".

Maurice Scève, was a French poet active in Lyon during the Renaissance period. He was the centre of the Lyonnese côterie that elaborated the theory of spiritual love, derived partly from Plato and partly from Petrarch. This spiritual love, which animated Antoine Héroet's Parfaicte Amye (1543) as well, owed much to Marsilio Ficino, the Florentine translator and commentator of Plato's works.

La Pléiade was a group of 16th-century French Renaissance poets whose principal members were Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay and Jean-Antoine de Baïf. The name was a reference to another literary group, the original Alexandrian Pleiad of seven Alexandrian poets and tragedians, corresponding to the seven stars of the Pleiades star cluster.

Jacques Pelletier du Mans, also spelled Peletier was a humanist, poet and mathematician of the French Renaissance.

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks to or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with aspirations to independence or autonomy. National epics frequently recount the origin of a nation, a part of its history, or a crucial event in the development of national identity such as other national symbols.

French poetry is a category of French literature. It may include Francophone poetry composed outside France and poetry written in other languages of France.

Jean Lemaire de Belges was a Walloon poet and historian, and pamphleteer who, writing in French, was the last and one of the best of the school of poetic 'rhétoriqueurs' (“rhetoricians”) and the chief forerunner, both in style and in thought, of the Renaissance humanists in France and Flanders.

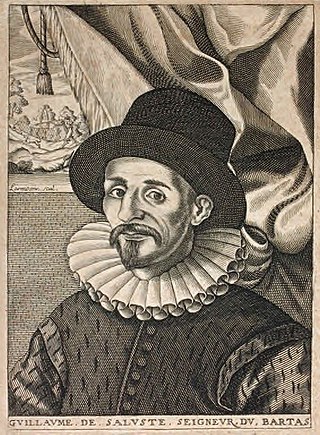

Guillaume de Salluste Du Bartas was a Gascon Huguenot courtier and poet. Trained as a doctor of law, he served in the court of Henri de Navarre for most of his career. Du Bartas was celebrated across sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe for his divine poetry, particularly L'Uranie (1574), Judit (1574), La Sepmaine; ou, Creation du monde (1578), and La Seconde Semaine (1584-1603).

Remy Belleau was a poet of the French Renaissance. He is most known for his paradoxical poems of praise for simple things and his poems about precious stones.

French Renaissance literature is, for the purpose of this article, literature written in French from the French invasion of Italy in 1494 to 1600, or roughly the period from the reign of Charles VIII of France to the ascension of Henry IV of France to the throne. The reigns of Francis I and his son Henry II are generally considered the apex of the French Renaissance. After Henry II's unfortunate death in a joust, the country was ruled by his widow Catherine de' Medici and her sons Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III, and although the Renaissance continued to flourish, the French Wars of Religion between Huguenots and Catholics ravaged the country.

— Opening lines from Gavin Douglas' Eneados, a translation, into Middle Scots of Virgil's Aeneid

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Francus or Francio is a mythological figure of French medieval historians which referred to a legendary eponymous king of the Franks, a descendant of the Trojans, founder of the Merovingian dynasty and forefather of Charlemagne. In the Renaissance, Francus was generally considered to be another name for the Trojan Astyanax saved from the destruction of Troy. He is not considered to be historical, but in fact an attempt by medieval and Renaissance chroniclers to model the founding of France upon the same illustrious tradition as that used by Virgil in his Aeneid.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Jehan Chardavoine was a French Renaissance composer mostly active in Paris. He was one of the first known editors of popular chansons, and the author, according to musicologist Julien Tiersot, of "the only volume of monodic songs from the 16th century that has survived to our days."

Jean Bastier de La Péruse (1529–1554) was a 16th-century French poet and playwright.

References

- ↑ Usher, Phillip John (2010). Ronsard's Franciad. New York: AMS Press. p. lvii.

- ↑ Usher, Phillip John (2009). "Non haec litora suasit Apollo : la Crète dans la Franciade de Ronsard". La Revue des amis de Ronsard. 22: 97–112.

- ↑ Braybrook, Jean (January 1989). "The aesthetics of fragmentation in Ronsard's Franciade". French Studies. xliii (1): 1. doi:10.1093/fs/xliii.1.1.

- ↑ Ternaux, Jean-Claude (2000). "La Franciade de Ronsard: Échec ou réussite?". La Revue des amis de Ronsard. 13: 117.

- ↑ Usher, Phillip John (2010). Ronsard's Franciad. p. lxi.

- ↑ Bjaï, Denis (2001). La Franciade sur le métier. Geneva: Droz.

- ↑ Rigolot, François (1988). "Ronsard's Pretext for Paratexts: The Case of the Franciade". SubStance. 17 (2): 33. doi:10.2307/3685137. JSTOR 3685137.

- ↑ Du Bellay, Joachim (1994). La défense et illustration de la langue française. Paris: Gallimard. p. 240.

- ↑ Usher, Phillip John (2010). Ronsard's Franciad. pp. 25–26, vv. 1–12.

- ↑ Wine, Kathleen (Fall 2011). "Pierre de Ronsard. The Franciad (1572). AMS Studies in the Renaissance 44. Ed. And trans. Phillip John Usher. Brooklyn: AMS Press, Inc., 2010. Lxviii + 272 pp. Index. Illus. Bibl. $162.50. ISBN: 978–0–404–62344–9". Renaissance Quarterly. 64 (3): 943–45. doi:10.1086/662895. S2CID 164114071.