Related Research Articles

Beer is one of the oldest types of alcoholic drinks in the world, and the most widely consumed. It is the third most popular drink overall after potable water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches, mainly derived from cereal grains—most commonly malted barley, though wheat, maize (corn), rice, and oats are also used. During the brewing process, fermentation of the starch sugars in the wort produces ethanol and carbonation in the resulting beer. Most modern beer is brewed with hops, which add bitterness and other flavours and act as a natural preservative and stabilising agent. Other flavouring agents such as gruit, herbs, or fruits may be included or used instead of hops. In commercial brewing, the natural carbonation effect is often removed during processing and replaced with forced carbonation.

Winemaking or vinification is the production of wine, starting with the selection of the fruit, its fermentation into alcohol, and the bottling of the finished liquid. The history of wine-making stretches over millennia. The science of wine and winemaking is known as oenology. A winemaker may also be called a vintner. The growing of grapes is viticulture and there are many varieties of grapes.

White wine is a wine that is fermented without skin contact. The colour can be straw-yellow, yellow-green, or yellow-gold. It is produced by the alcoholic fermentation of the non-coloured pulp of grapes, which may have a skin of any colour. White wine has existed for at least 4,000 years.

Malolactic conversion is a process in winemaking in which tart-tasting malic acid, naturally present in grape must, is converted to softer-tasting lactic acid. Malolactic fermentation is most often performed as a secondary fermentation shortly after the end of the primary fermentation, but can sometimes run concurrently with it. The process is standard for most red wine production and common for some white grape varieties such as Chardonnay, where it can impart a "buttery" flavor from diacetyl, a byproduct of the reaction.

Kilju is the Finnish word for home made alcoholic beverage typically made of sugar, yeast, and water.

Campden tablets are a sulphur-based product that are used primarily to sterilize wine, cider and in beer making to kill bacteria and to inhibit the growth of most wild yeast. They are also used to eliminate both free chlorine and the more stable form, chloramine, from water solutions. Campden tablets allow the amateur brewer to easily measure small quantities of sodium metabisulfite, so they can be used to protect against wild yeast and bacteria without affecting flavour. Untreated cider must frequently suffers from acetobacter contamination causing vinegar spoilage. Yeasts are resistant to the tablets but the acetobacter are easily killed off, hence treatment is important in cider production.

Industrial fermentation is the intentional use of fermentation in manufacturing processes. In addition to the mass production of fermented foods and drinks, industrial fermentation has widespread applications in chemical industry. Commodity chemicals, such as acetic acid, citric acid, and ethanol are made by fermentation. Moreover, nearly all commercially produced industrial enzymes, such as lipase, invertase and rennet, are made by fermentation with genetically modified microbes. In some cases, production of biomass itself is the objective, as is the case for single-cell proteins, baker's yeast, and starter cultures for lactic acid bacteria used in cheesemaking.

A wine fault is a sensory-associated (organoleptic) characteristic of a wine that is unpleasant, and may include elements of taste, smell, or appearance, elements that may arise from a "chemical or a microbial origin", where particular sensory experiences might arise from more than one wine fault. Wine faults may result from poor winemaking practices or storage conditions that lead to wine spoilage.

Wort is the liquid extracted from the mashing process during the brewing of beer or whisky. Wort contains the sugars, the most important being maltose and maltotriose, that will be fermented by the brewing yeast to produce alcohol. Wort also contains crucial amino acids to provide nitrogen to the yeast as well as more complex proteins contributing to beer head retention and flavour.

Symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) is a culinary symbiotic fermentation culture (starter) consisting of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeast which arises in the preparation of sour foods and beverages such as kombucha. Beer and wine also undergo fermentation with yeast, but the lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria components unique to SCOBY are usually viewed as a source of spoilage rather than a desired addition. Both LAB and AAB enter on the surface of barley and malt in beer fermentation and grapes in wine fermentation; LAB lowers the pH of the beer/wine while AAB takes the ethanol produced from the yeast and oxidizes it further into vinegar, resulting in a sour taste and smell. AAB are also responsible for the formation of the cellulose SCOBY.

The process of fermentation in winemaking turns grape juice into an alcoholic beverage. During fermentation, yeasts transform sugars present in the juice into ethanol and carbon dioxide. In winemaking, the temperature and speed of fermentation are important considerations as well as the levels of oxygen present in the must at the start of the fermentation. The risk of stuck fermentation and the development of several wine faults can also occur during this stage, which can last anywhere from 5 to 14 days for primary fermentation and potentially another 5 to 10 days for a secondary fermentation. Fermentation may be done in stainless steel tanks, which is common with many white wines like Riesling, in an open wooden vat, inside a wine barrel and inside the wine bottle itself as in the production of many sparkling wines.

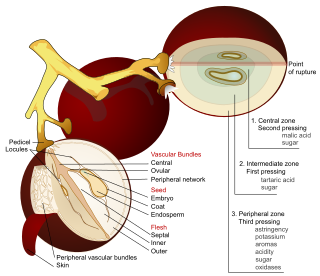

The acids in wine are an important component in both winemaking and the finished product of wine. They are present in both grapes and wine, having direct influences on the color, balance and taste of the wine as well as the growth and vitality of yeast during fermentation and protecting the wine from bacteria. The measure of the amount of acidity in wine is known as the “titratable acidity” or “total acidity”, which refers to the test that yields the total of all acids present, while strength of acidity is measured according to pH, with most wines having a pH between 2.9 and 3.9. Generally, the lower the pH, the higher the acidity in the wine. There is no direct connection between total acidity and pH. In wine tasting, the term “acidity” refers to the fresh, tart and sour attributes of the wine which are evaluated in relation to how well the acidity balances out the sweetness and bitter components of the wine such as tannins. Three primary acids are found in wine grapes: tartaric, malic, and citric acids. During the course of winemaking and in the finished wines, acetic, butyric, lactic, and succinic acids can play significant roles. Most of the acids involved with wine are fixed acids with the notable exception of acetic acid, mostly found in vinegar, which is volatile and can contribute to the wine fault known as volatile acidity. Sometimes, additional acids, such as ascorbic, sorbic and sulfurous acids, are used in winemaking.

Cider is an alcoholic beverage made from the fermented juice of apples. Cider is widely available in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. The UK has the world's highest per capita consumption, as well as the largest cider-producing companies. Ciders from the South West of England are generally higher in alcoholic content. Cider is also popular in many Commonwealth countries, such as India, South Africa, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. As well as the UK and its former colonies, cider is popular in Portugal, France, Friuli, and northern Spain. Germany also has its own types of cider with Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse producing a particularly tart version known as Apfelwein. In the U.S. and Canada, varieties of alcoholic cider are often called hard cider to distinguish it from non-alcoholic apple cider or "sweet cider", also made from apples. In Canada, cider cannot contain less than 2.5% or over 13% absolute alcohol by volume.

This glossary of winemaking terms lists some of terms and definitions involved in making wine, fruit wine, and mead.

Autolysis in winemaking relates to the complex chemical reactions that take place when a wine spends time in contact with the lees, or dead yeast cells, after fermentation. While for some wines - and all beers - autolysis is undesirable, it is a vital component in shaping the flavors and mouth feel associated with premium Champagne production. The practice of leaving a wine to age on its lees has a long history in winemaking dating back to Roman winemaking. The chemical process and details of autolysis were not originally understood scientifically, but the positive effects such as a creamy mouthfeel, breadlike and floral aromas, and reduced astringency were noticed early in the history of wine.

When drinking beer, there are many factors to be considered. Principal among them are bitterness, the variety of flavours present in the beverage and their intensity, alcohol content, and colour. Standards for those characteristics allow a more objective and uniform determination to be made on the overall qualities of any beer.

The role of yeast in winemaking is the most important element that distinguishes wine from fruit juice. In the absence of oxygen, yeast converts the sugars of the fruit into alcohol and carbon dioxide through the process of fermentation. The more sugars in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine if the yeast are allowed to carry out fermentation to dryness. Sometimes winemakers will stop fermentation early in order to leave some residual sugars and sweetness in the wine such as with dessert wines. This can be achieved by dropping fermentation temperatures to the point where the yeast are inactive, sterile filtering the wine to remove the yeast or fortification with brandy or neutral spirits to kill off the yeast cells. If fermentation is unintentionally stopped, such as when the yeasts become exhausted of available nutrients and the wine has not yet reached dryness, this is considered a stuck fermentation.

Yeast assimilable nitrogen or YAN is the combination of free amino nitrogen (FAN), ammonia (NH3) and ammonium (NH4+) that is available for a yeast, e.g. the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, to use during fermentation. Outside of the fermentable sugars glucose and fructose, nitrogen is the most important nutrient needed to carry out a successful fermentation that doesn't end prior to the intended point of dryness or sees the development of off-odors and related wine faults. To this extent winemakers will often supplement the available YAN resources with nitrogen additives such as diammonium phosphate (DAP).

The chemical compounds in beer give it a distinctive taste, smell and appearance. The majority of compounds in beer come from the metabolic activities of plants and yeast and so are covered by the fields of biochemistry and organic chemistry. The main exception is that beer contains over 90% water and the mineral ions in the water (hardness) can have a significant effect upon the taste.

A beerfault or defect is a flavor deterioration caused by chemical changes to the organic compounds in beer, either due to improper production processes or storage. Various chemicals, including aldehydes, lipids, sulfur compounds, and fermentation by-products, can have a noticeable impact on flavour, even with slight changes. When the concentration of one or more of these chemicals exceeds the standard threshold, flavour characteristics may change, creating a flavour defect.

References

- 1 2 K. Fugelsang, C. Edwards Wine Microbiology Second Edition pgs 16-17, 35, 115-117, 124-129 Springer Science and Business Media , New York (2010) ISBN 0387333495

- ↑ Sara E. Spayd and Joy Andersen-Bagge "Free Amino Acid Composition of Grape Juice From 12 Vitis vinifera Cultivars in Washington" Am. J. Enol. Vitic 1996 vol. 47 no. 4 389-402