The mass media in Romania refers to mass media outlets based in Romania. Television, magazines, and newspapers are all operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues. The Constitution of Romania guarantees freedom of speech. As a country in transition, the Romanian media system is under transformation.

The Government of Bhutan has been a constitutional monarchy since 18 July 2008. The King of Bhutan is the head of state. The executive power is exercised by the Lhengye Zhungtshog, or council of ministers, headed by the Prime Minister. Legislative power is vested in the bicameral Parliament, both the upper house, National Council, and the lower house, National Assembly. A royal edict issued on April 22, 2007 lifted the previous ban on political parties in anticipation of the National Assembly elections in the following year. In 2008, Bhutan adopted its first modern Constitution, codifying the institutions of government and the legal framework for a democratic multi-party system.

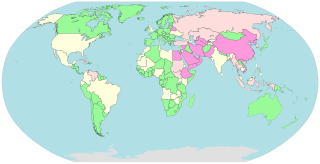

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exercised freely. Such freedom implies the absence of interference from an overreaching state; its preservation may be sought through the constitution or other legal protection and security. It is in opposition to paid press, where communities, police organizations, and governments are paid for their copyrights.

Gross National Happiness, sometimes called Gross Domestic Happiness (GDH), is a philosophy that guides the government of Bhutan. It includes an index which is used to measure the collective happiness and well-being of a population. Gross National Happiness Index is instituted as the goal of the government of Bhutan in the Constitution of Bhutan, enacted on 18 July 2008.

In Iran, censorship was ranked among the world's most extreme in 2023. Reporters Without Borders ranked Iran 177 out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index, which ranks countries from 1 to 180 based on the level of freedom of the press. Reporters Without Borders described Iran as “one of the world’s five biggest prisons for media personnel" in the 40 years since the revolution. In the Freedom House Index, Iran scored low on political rights and civil liberties and has been classified as 'not free.'

Censorship in Bhutan refers to the way in which the Government of Bhutan controls information within its borders. There are no laws that either guarantee citizens' right to information or explicitly structure a censorship scheme. However, censorship in Bhutan is still conducted by restrictions on the ownership of media outlets, licensing of journalists, and the blocking of websites.

Censorship in Thailand involves the strict control of political news under successive governments, including by harassment and manipulation.

The various mass media in Bhutan have historically been government-controlled, although this has changed in recent years. The country has its own newspapers, television and radio broadcasters and Internet Service Providers.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in Bhutan face legal challenges that are not faced by non-LGBT people. Same-sex sexual activity was decriminalised in Bhutan on 17 February 2021.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless, the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws.

Human rights in Bhutan are those outlined in Article 7 of its Constitution. The Royal Government of Bhutan has affirmed its commitment to the "enjoyment of all human rights" as integral to the achievement of 'gross national happiness' (GNH); the unique principle which Bhutan strives for, as opposed to fiscally based measures such as GDP.

Censorship in Bangladesh refers to the government censorship of the press and infringement of freedom of speech. Article 39 of the constitution of Bangladesh protects free speech.

Censorship in Armenia is generally non-existent, except in some limited incidents.

Censorship in Ecuador refers to all actions which can be considered as suppression in speech in Ecuador. In the Freedom of the Press Report 2016 by Freedom House, the press in Ecuador is classified as "not free". The 2016 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders placed Ecuador in the "noticeable problems" category for press freedom, ranking the country 109 out of 180.

The Wire is an Indian nonprofit news and opinion website. It was founded in 2015 by Siddharth Varadarajan, Sidharth Bhatia, and M. K. Venu. It counts among the news outlets that are independent of the Indian government, and has been subject to several defamation suits by businessmen and politicians. In 2022, one of its reporters fabricated several news stories, and was then fired.

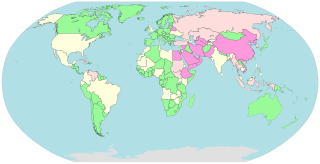

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.

Freedom of the press in India is legally protected by the Amendment to the constitution of India, while the sovereignty, national integrity, and moral principles are generally protected by the law of India to maintain a hybrid legal system for independent journalism. In India, media bias or misleading information is restricted under the certain constitutional amendments as described by the country's constitution. The media crime is covered by the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which is applicable to all substantive aspects of criminal law.

Freedom of the press in Bangladesh refers to the censorship and endorsement on public opinions, fundamental rights, freedom of expression, human rights, explicitly mass media such as the print, broadcast and online media as described or mentioned in the constitution of Bangladesh. The country's press is legally regulated by the certain amendments, while the sovereignty, national integrity and sentiments are generally protected by the law of Bangladesh to maintain a hybrid legal system for independent journalism and to protect fundamental rights of the citizens in accordance with secularism and media law. In Bangladesh, media bias and disinformation is restricted under the certain constitutional amendments as described by the country's post-independence constitution.

Freedom of the press in Myanmar refers to the freedom of speech, expression, right to information, and mass media in particular. The media of Myanmar is regulated by the law of Myanmar, the News Media Law which prevent spreading or circulating media bias. It also determines freedom of expression for media houses, journalists, and other individuals or organisations working within the country. Its print, broadcast and Internet media is regulated under the News Media Law, nominally compiled by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and international standards on freedom of expression.

Namgay Zam is a Bhutanese journalist and activist. Having made her name as a producer and anchor on the public Bhutan Broadcasting Service, she now serves as executive director of the Journalists' Association of Bhutan. A 2016 lawsuit against Zam was considered the first test case of the country's press freedoms after its democratic transition.