Merrill C. Meigs Field Airport was a single-runway airport in Chicago that was in operation from 1948 to 2003, when it was bulldozed overnight by then-mayor Richard M. Daley. The airport was located on Northerly Island, an artificial peninsula on Lake Michigan adjacent to downtown Chicago, the second-largest business district in the Western Hemisphere. By 1955, Meigs Field had become the busiest single-strip airport in the United States. The airport was a familiar sight on the downtown lakefront. The latest air traffic tower was built in 1952, and the terminal was dedicated in 1961. The airfield was named for Merrill C. Meigs.

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of African American military pilots and airmen who fought in World War II. They formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group (Medium) of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). The name also applies to the navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs, nurses, cooks, and other support personnel. The Tuskegee airmen received praise for their excellent combat record earned while protecting American bombers from enemy fighters. The group was awarded three Distinguished Unit Citations.

Sharpe Field is a closed private use airport located six nautical miles northwest of the central business district of Tuskegee, a city in Macon County, Alabama, United States. This airport is privately owned by the Bradbury Family Partnership.

Walnut Ridge Regional Airport is a city-owned public-use airport located four nautical miles (7 km) northeast of the central business district of Walnut Ridge, a city in Lawrence County, Arkansas, United States. According to the FAA's National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems for 2009–2013, its FAA airport category is general aviation.

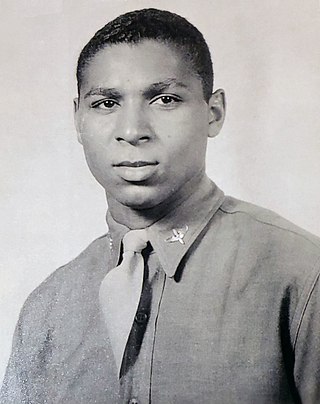

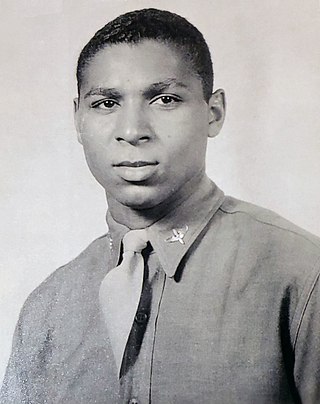

Milton Pitts Crenchaw was an American aviator who served with the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II and was the first Arkansan to be trained by the federal government as a civilian licensed pilot. He served during World War II as a civilian flight instructor. He was one of the two original supervising squadron members. In 1998 he was inducted into the Arkansas Aviation Hall of Fame. The grandson of a slave, he was known as the "father of black aviation in Arkansas" who broke through color barriers in the military.

Freeman Municipal Airport is a public use airport located two nautical miles (4 km) southwest of the central business district of Seymour, a city in Jackson County, Indiana, United States. It is owned by the Seymour Airport Authority. This airport is included in the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems for 2021–2025, which categorized it as a general aviation facility.

The Red Tail Squadron, part of the non-profit Commemorative Air Force (CAF), known as the Red Tail Project until June 2011, maintains and flies a World War II era North American P-51C Mustang. The twice-restored aircraft flies to create interest in the history and accomplishments of the members of the World War II-era 332nd Fighter Group, also known as the Tuskegee Airmen, whose distinctive red markings on the tails of the P-51s they flew during that war, gave the organization its name.

Freeman Army Airfield is an inactive United States Army Air Forces base. It is located 2.6 miles (4.2 km) south-southwest of Seymour, Indiana.

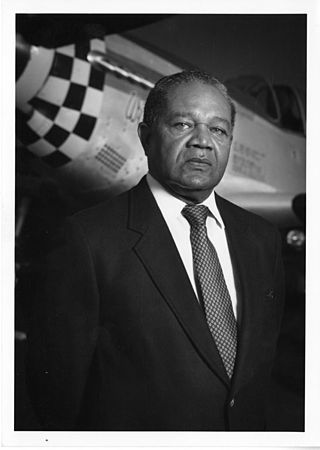

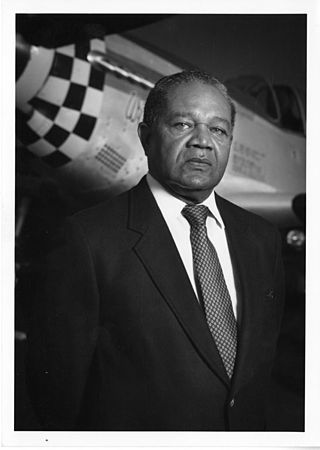

Brigadier General Charles Edward McGee was an American fighter pilot who was one of the first African American aviators in the United States military and one of the last living members of the Tuskegee Airmen. McGee first began his career in World War II flying with the Tuskegee Airmen, an all African American military pilot group at a time of segregation in the armed forces. His military aviation career lasted 30 years in which McGee flew 409 combat missions in World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam War.

Louis Rayfield Purnell, Sr. was a noted curator at the United States' National Air and Space Museum and earlier in life, a decorated Tuskegee Airman. At the museum, he became expert in space flight artifacts, particularly spacesuits, and was instrumental in curating artifacts related to space exploration, during the pivotal years of the 1960s and into the 1980s. Purnell was the first African-American to become a curator at the Smithsonian Institution.

The Texas Air & Space Museum is an aviation museum located near Rick Husband Amarillo International Airport in Amarillo, Texas. The museum displays civilian and military aircraft, as well as a wide range of air and space artifacts.

Fitzroy "Buck" Newsum was an American military pilot and officer who was one of the original members of the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II. He retired as a colonel in 1970.

Mitchell Higginbotham was a U.S. Army Air Force officer who was a member of the African American World War II fighter group known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

First Lieutenant Robert L. Martin (WIA) was a Tuskegee Airman active during World War II. His aircraft was shot down after a raid on an airfield in Yugoslavia. He was a recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

2nd Lt. Alfred M. Gorham (1920–2009) (POW) was a Tuskegee Airman from Waukesha, Wisconsin. He was the only Tuskegee Airman from Wisconsin, and he was a prisoner of war after his plane went down over Munich, Germany in World War II.

Andrew D. Turner was an officer in the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) and a fighter pilot and commanding officer of the all-African American 332nd Fighter Group's 100th Fighter Squadron, best known as the all-African American Tuskegee Airmen, "Red Tails," or among enemy German pilots, “Schwartze Vogelmenschen”.

George Levi Knox II was a U.S. Army Air Force/U.S. Air Force officer, combat fighter pilot and Adjutant with the all-African American 332nd Fighter Group's 100th Fighter Squadron, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen. One of the 1,007 documented Tuskegee Airmen Pilots, he was a member of the Tuskegee Airmen's third-ever aviation cadet class, and one of the first twelve African Americans to become combat fighter pilots. He was the second Indiana native to graduate from the Tuskegee Advanced Flying School (TAFS).

Wilson Vashon Swampy Eagleson II, was a United States Army Air Force officer and combat fighter pilot with the 332nd Fighter Group's 99th Fighter Squadron, best known as the Tuskegee Airmen. One of 1,007 documented Tuskegee Airmen Pilots, Eagleson was credited with two confirmed enemy German aerial kills and two probable aerial kills.

Columbia Field, originally Curtiss Field, is a former airfield near Valley Stream within the Town of Hempstead on Long Island, New York. Between 1929 and 1933 it was a public airfield named Curtiss Field after the Curtiss-Wright aircraft corporation that owned it. The public airfield closed after 1933, but aircraft continued to be manufactured there primarily by Columbia Aircraft Corporation, which gave the private airfield its name.