Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a potter is also called a pottery. The definition of pottery, used by the ASTM International, is "all fired ceramic wares that contain clay when formed, except technical, structural, and refractory products". End applications include tableware, decorative ware, sanitaryware, and in technology and industry such as electrical insulators and laboratory ware. In art history and archaeology, especially of ancient and prehistoric periods, pottery often means vessels only, and sculpted figurines of the same material are called terracottas.

Longquan celadon (龍泉青瓷) is a type of green-glazed Chinese ceramic, known in the West as celadon or greenware, produced from about 950 to 1550. The kilns were mostly in Lishui prefecture in southwestern Zhejiang Province in the south of China, and the north of Fujian Province. Overall a total of some 500 kilns have been discovered, making the Longquan celadon production area one of the largest historical ceramic producing areas in China. "Longquan-type" is increasingly preferred as a term, in recognition of this diversity, or simply "southern celadon", as there was also a large number of kilns in north China producing Yaozhou ware or other Northern Celadon wares. These are similar in many respects, but with significant differences to Longquan-type celadon, and their production rose and declined somewhat earlier.

Stoneware is a rather broad term for pottery fired at a relatively high temperature. A modern technical definition is a vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic made primarily from stoneware clay or non-refractory fire clay. End applications include tableware, decorative ware such as vases.

Pottery and porcelain, is one of the oldest Japanese crafts and art forms, dating back to the Neolithic period. Kilns have produced earthenware, pottery, stoneware, glazed pottery, glazed stoneware, porcelain, and blue-and-white ware. Japan has an exceptionally long and successful history of ceramic production. Earthenwares were made as early as the Jōmon period, giving Japan one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world. Japan is further distinguished by the unusual esteem that ceramics holds within its artistic tradition, owing to the enduring popularity of the tea ceremony.

Celadon is a term for pottery denoting both wares glazed in the jade green celadon color, also known as greenware or "green ware", and a type of transparent glaze, often with small cracks, that was first used on greenware, but later used on other porcelains. Celadon originated in China, though the term is purely European, and notable kilns such as the Longquan kiln in Zhejiang province are renowned for their celadon glazes. Celadon production later spread to other parts of East Asia, such as Japan and Korea as well as Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand. Eventually, European potteries produced some pieces, but it was never a major element there. Finer pieces are in porcelain, but both the color and the glaze can be produced in stoneware and earthenware. Most of the earlier Longquan celadon is on the border of stoneware and porcelain, meeting the Chinese but not the European definitions of porcelain.

Salt-glaze or salt glaze pottery is pottery, usually stoneware, with a glaze of glossy, translucent and slightly orange-peel-like texture which was formed by throwing common salt into the kiln during the higher temperature part of the firing process. Sodium from the salt reacts with silica in the clay body to form a glassy coating of sodium silicate. The glaze may be colourless or may be coloured various shades of brown, blue, or purple.

"Blue and white pottery" covers a wide range of white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration is commonly applied by hand, originally by brush painting, but nowadays by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. The cobalt pigment is one of the very few that can withstand the highest firing temperatures that are required, in particular for porcelain, which partly accounts for its long-lasting popularity. Historically, many other colours required overglaze decoration and then a second firing at a lower temperature to fix that.

Medieval Islamic pottery occupied a geographical position between Chinese ceramics, the unchallenged leaders of Eurasian production, and the pottery of the Byzantine Empire and Europe. For most of the period it can fairly be said to have been between the two in terms of aesthetic achievement and influence as well, borrowing from China and exporting to and influencing Byzantium and Europe. The use of drinking and eating vessels in gold and silver, the ideal in ancient Rome and Persia as well as medieval Christian societies, is prohibited by the Hadiths, with the result that pottery and glass were used for tableware by Muslim elites, as pottery also was in China but was much rarer in Europe and Byzantium. In the same way, Islamic restrictions greatly discouraged figurative wall-painting, encouraging the architectural use of schemes of decorative and often geometrically patterned titles, which are the most distinctive and original specialty of Islamic ceramics.

Biscuit porcelain, bisque porcelain or bisque is unglazed, white porcelain treated as a final product, with a matte appearance and texture to the touch. It has been widely used in European pottery, mainly for sculptural and decorative objects that are not tableware and so do not need a glaze for protection.

Transfer printing is a method of decorating pottery or other materials using an engraved copper or steel plate from which a monochrome print on paper is taken which is then transferred by pressing onto the ceramic piece. Pottery decorated using the technique is known as transferware or transfer ware.

Ding ware, Ting ware or Dingyao are Chinese ceramics, mostly porcelain, that were produced in the prefecture of Dingzhou in Hebei in northern China. The main kilns were at Jiancicun or Jianci in Quyang County. They were produced between the Tang and Yuan dynasties of imperial China, though their finest period was in the 11th century, under the Northern Song. The kilns "were in almost constant operation from the early eighth until the mid-fourteenth century."

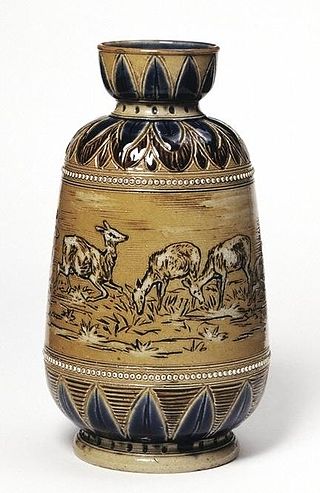

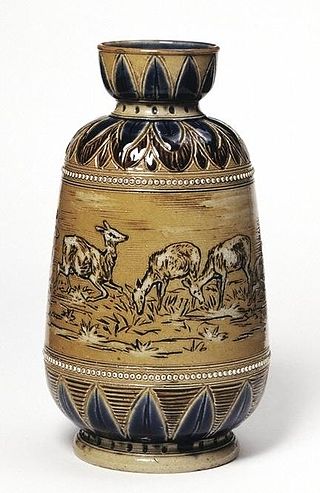

Royal Doulton is an English ceramic and home accessories manufacturer that was founded in 1815. Operating originally in Vauxhall, London, and later moving to Lambeth, in 1882 it opened a factory in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, in the centre of English pottery. From the start, the backbone of the business was a wide range of utilitarian wares, mostly stonewares, including storage jars, tankards and the like, and later extending to drain pipes, lavatories, water filters, electrical porcelain and other technical ceramics. From 1853 to 1901, its wares were marked Doulton & Co., then from 1901, when a royal warrant was given, Royal Doulton.

Chinese ceramics show a continuous development since pre-dynastic times and are one of the most significant forms of Chinese art and ceramics globally. The first pottery was made during the Palaeolithic era. Chinese ceramics range from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or kilns, to the sophisticated Chinese porcelain wares made for the imperial court and for export. Porcelain was a Chinese invention and is so identified with China that it is still called "china" in everyday English usage.

Sprigging or sprigged decoration is a technique for decorating pottery with low relief shapes made separately from the main body and applied to it before firing. Usually thin press moulded shapes are applied to greenware or bisque. The resulting pottery is termed sprigged ware, and the added piece is a "sprig". The technique may also be described by terms such as "applied relief decoration", especially in non-European pottery.

Art pottery is a term for pottery with artistic aspirations, made in relatively small quantities, mostly between about 1870 and 1930. Typically, sets of the usual tableware items are excluded from the term; instead the objects produced are mostly decorative vessels such as vases, jugs, bowls and the like which are sold singly. The term originated in the later 19th century, and is usually used only for pottery produced from that period onwards. It tends to be used for ceramics produced in factory conditions, but in relatively small quantities, using skilled workers, with at the least close supervision by a designer or some sort of artistic director. Studio pottery is a step up, supposed to be produced in even smaller quantities, with the hands-on participation of an artist-potter, who often performs all or most of the production stages. But the use of both terms can be elastic. Ceramic art is often a much wider term, covering all pottery that comes within the scope of art history, but "ceramic artist" is often used for hands-on artist potters in studio pottery.

John Dwight was an English ceramic manufacturer, who founded the Fulham Pottery in London and pioneered the production of stoneware in England.

John Philip Elers and his brother David Elers were Dutch silversmiths who came to England in the 1680s and turned into potters. The Elers brothers were important innovators in English pottery, bringing redware or unglazed stoneware to Staffordshire pottery. Arguably they were the first producers of "fine pottery" in North Staffordshire, and although their own operations were not financially successful, they seem to have had a considerable influence on the following generation, who led the explosive growth of the industry in the 18th century.

Redware as a single word is a term for at least two types of pottery of the last few centuries, in Europe and North America. Red ware as two words is a term used for pottery, mostly by archaeologists, found in a very wide range of places. However, these distinct usages are not always adhered to, especially when referring to the many different types of pre-colonial red wares in the Americas, which may be called "redware".

Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including artistic pottery, including tableware, tiles, figurines and other sculpture. As one of the plastic arts, ceramic art is one of the visual arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, such as pottery or sculpture, most are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artefacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery". In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery.

The original Castleford Pottery operated from c. 1793 to 1820 in Castleford in Yorkshire, England. It was owned by David Dunderdale, and is especially known for making "a smear-glazed, finely moulded, white stoneware". This included feldspar, giving it a degree of opacity unusual in a stoneware. The designs typically included relief elements, and edges of the main shape and the panels into which the body was divided were often highlighted with blue overglaze enamel. Most pieces were teapots or accompanying milk jugs, sugar bowls and slop bowls, and the shapes often derived from those used in contemporary silversmithing.