Textile arts are arts and crafts that use plant, animal, or synthetic fibers to construct practical or decorative objects.

Shroud usually refers to an item, such as a cloth, that covers or protects some other object. The term is most often used in reference to burial sheets, mound shroud, grave clothes, winding-cloths or winding-sheets, such as the famous Shroud of Turin, tachrichim that Jews are dressed in for burial, or the white cotton kaffan sheets Muslims are wrapped in for burial.

Cahuachi, in Peru, was a major ceremonial center of the Nazca culture, based from 1 AD to about 500 AD in the coastal area of the Central Andes. It overlooked some of the Nazca lines. The Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Orefici has been excavating at the site for the past few decades. The site contains over 40 mounds topped with adobe structures. The huge architectural complex covers 0.6 sq. miles (1.5 km2) at 365 meters above sea level. The American archeologist Helaine Silverman has also conducted long term, multi-stage research and written about the full context of Nazca society at Cahuachi, published in a lengthy study in 1993.

The Wari were a Middle Horizon civilization that flourished in the south-central Andes and coastal area of modern-day Peru, from about 500 to 1000 AD.

Momia Juanita, also known as the Lady of Ampato, is the well-preserved frozen body of a girl from the Inca Empire who was killed as a human sacrifice to the Inca gods sometime between 1440 and 1480, when she was approximately 12–15 years old. She was discovered on the dormant stratovolcano Mount Ampato in 1995 by anthropologist Johan Reinhard and his Peruvian climbing partner, Miguel Zárate. She is known as the Lady of Ampato because she was found on top of Mount Ampato. Her other nickname, the Ice Maiden, derives from the cold conditions and freezing temperatures that preserved her body on Mount Ampato.

The Nazca culture was the archaeological culture that flourished from c. 100 BC to 800 AD beside the arid, southern coast of Peru in the river valleys of the Rio Grande de Nazca drainage and the Ica Valley. Strongly influenced by the preceding Paracas culture, which was known for extremely complex textiles, the Nazca produced an array of crafts and technologies such as ceramics, textiles, and geoglyphs.

Double cloth or double weave is a kind of woven textile in which two or more sets of warps and one or more sets of weft or filling yarns are interconnected to form a two-layered cloth. The movement of threads between the layers allows complex patterns and surface textures to be created.

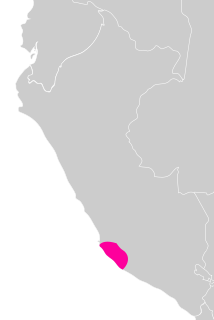

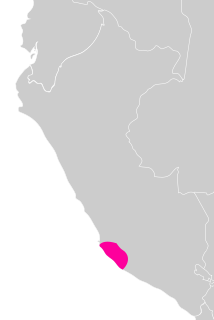

The Paracas culture was an Andean society existing between approximately 800 BCE and 100 BCE, with an extensive knowledge of irrigation and water management and that made significant contributions in the textile arts. It was located in what today is the Ica Region of Peru. Most information about the lives of the Paracas people comes from excavations at the large seaside Paracas site on the Paracas Peninsula, first formally investigated in the 1920s by Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello.

Julio César Tello was a Peruvian archaeologist. Tello is considered the "father of Peruvian archeology" and was the first indigenous archaeologist in South America.

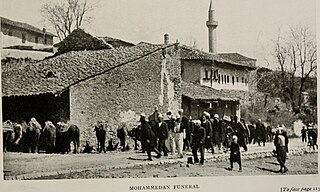

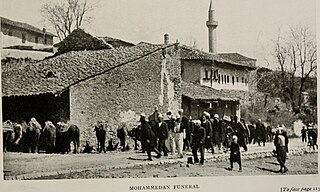

Funerals and funeral prayers in Islam follow fairly specific rites, though they are subject to regional interpretation and variation in custom. In all cases, however, sharia calls for burial of the body as soon as possible, preceded by a simple ritual involving bathing and shrouding the body, followed by salah (prayer). Burial is usually within 24 hours of death to protect the living from any sanitary issues, except in the case of a person killed in battle or when foul play is suspected; in those cases it is important to determine the cause of death before burial. Cremation of the body is strictly forbidden in Islam.

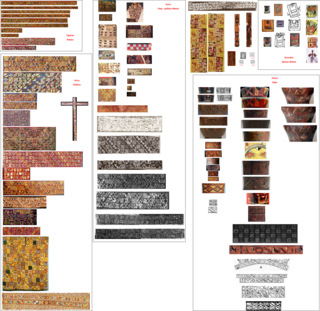

The Andean textile tradition once spanned from the Pre-Columbian to the Colonial era throughout the western coast of South America, but was mainly concentrated in Peru. The arid desert conditions along the coast of Peru have allowed for the preservation of these dyed textiles, which can date to 6000 years old. Many of the surviving textile samples were from funerary bundles, however, these textiles also encompassed a variety of functions. These functions included the use of woven textiles for ceremonial clothing or cloth armor as well as knotted fibers for record-keeping. The textile arts were instrumental in political negotiations, and were used as diplomatic tools that were exchanged between groups. Textiles were also used to communicate wealth, social status, and regional affiliation with others. The cultural emphasis on the textile arts was often based on the believed spiritual and metaphysical qualities of the origins of materials used, as well as cosmological and symbolic messages within the visual appearance of the textiles. Traditionally, the thread used for textiles was spun from indigenous cotton plants, as well as alpaca and llama wool.

Hmong Textile Art consists of traditional and modern textile arts and crafts produced by the Hmong people. Traditional Hmong textile examples include hand-spun hemp cloth production, basket weaving, batik dyeing, and a unique form of embroidery known as flower cloth or Paj Ntaub in the Hmong language RPA. The most widely recognized modern style of Hmong textile art is a form of embroidery derived from Paj Ntaub known as story cloth.

The Lima culture was an indigenous civilization which existed in modern-day Lima, Peru during the Early Intermediate Period, extending from roughly 100 to 650. This pre-Incan culture, which overlaps with surrounding Paracas, Moche, and Nasca civilizations, was located in the desert coastal strip of Peru in the Chillon, Rimac and Lurin River valleys. It can be difficult to differentiate the Lima culture from surrounding cultures due to both its physical proximity to other, and better documented cultures, in Coastal Peru, and because it is chronologically very close, if not over lapped, by these other cultures as well. These factors all help contribute to the obscurity of the Lima culture, of which much information is still left to be learned.

The textiles of Mexico have a long history. The making of fibers, cloth and other textile goods has existed in the country since at least 1400 BCE. Fibers used during the pre-Hispanic period included those from the yucca, palm and maguey plants as well as the use of cotton in the hot lowlands of the south. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Spanish introduced new fibers such as silk and wool as well as the European foot treadle loom. Clothing styles also changed radically. Fabric was produced exclusively in workshops or in the home until the era of Porfirio Díaz, when the mechanization of weaving was introduced, mostly by the French. Today, fabric, clothes and other textiles are both made by craftsmen and in factories. Handcrafted goods include pre-Hispanic clothing such as huipils and sarapes, which are often embroidered. Clothing, rugs and more are made with natural and naturally dyed fibers. Most handcrafts are produced by indigenous people, whose communities are concentrated in the center and south of the country in states such as Mexico State, Oaxaca and Chiapas. The textile industry remains important to the economy of Mexico although it has suffered setback due to competition by cheaper goods produced in countries such as China, India and Vietnam.

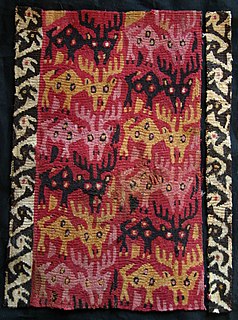

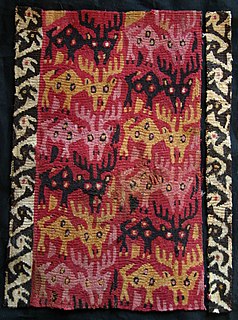

The Paracas textiles were found at a necropolis in Peru in the 1920s. The necropolis held 420 bodies who had been mummified and wrapped in embroidered textiles of the Paracas culture in 200–300 BCE. The examples in the British Museum show flying shamans who hold severed heads by their hair.

Textile arts of indigenous peoples of the Americas are decorative, utilitarian, ceremonial, or conceptual artworks made from plant, animal, or synthetic fibers by native peoples of both North and South America.

A chuspas is a pouch that is used to carry coca and cocoa leaves, used primarily in the Andean region of South America. Both textiles and coca are very important to the people in Andean South America. These chuspas are a vital piece of culture and are especially important to combat the bitter cold in the mountainous zones of the Andes. These bags are also a way to showcase the cloth which in itself is a primary artistic medium. Highland textiles are traditionally woven from the hair of native camelids, usually the domesticated alpacas and llamas, and more rarely, wild vicuña and guanaco. These pouches are important symbols of social identity. As part of this tradition, chuspas show to the rest of their people how skilled they are in weaving. They can express their artistic skills and display their cultural affiliation by creating these chuspas.

The village of Pipili, Puri district, Odisha, India, is well known for its appliqué work, also known as Chandua. "Appliqué" comes from the French word appliquer, meaning "to put on". There are two variants to this technique: appliqué, where a fabric shape is sewn over a base layer, and reverse appliqué, wherein two layers of fabric are laid down, and a shape is subsequently cut out from the upper layer, exposing the lower layer, before both are stitched together. It is one of the products which has been granted Geographical Indication (GI) by the government of India.

The Muisca inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Colombian Andes before the arrival of the Spanish and were an advanced civilisation. They mummified the higher social class members of their society, mainly the zipas, zaques, caciques, priests and their families. The mummies would be placed in caves or in dedicated houses ("mausoleums") and were not buried.

Cumbi was a fine luxurious fabric of the Inca Empire. Elites used to offer cumbi to the rulers, and it was a reserved cloth for Royalty. Common people were not allowed to use Cumbi. Cumbi was a phenomenal textile art of Andean textiles.