Vercingetorix was a Gallic king and chieftain of the Arverni tribe who united the Gauls in a failed revolt against Roman forces during the last phase of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars. After surrendering to Caesar and spending almost six years in prison, he was executed in Rome.

Commentarii de Bello Gallico, also Bellum Gallicum, is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Caesar describes the battles and intrigues that took place in the nine years he spent fighting the Celtic and Germanic peoples in Gaul that opposed Roman conquest.

Legio X Equestris, a Roman legion, was levied by Julius Caesar in 61 BC when he was the Governor of Hispania Ulterior. The Tenth was the first legion levied personally by Caesar and was consistently his most trusted. Legio X was famous in its day and throughout history, because of its portrayal in Caesar's Commentaries and the prominent role the Tenth played in his Gallic campaigns. Its soldiers were discharged in 45 BC. Its remnants were reconstituted, fought for Mark Antony and Octavian, disbanded, and later merged into X Gemina.

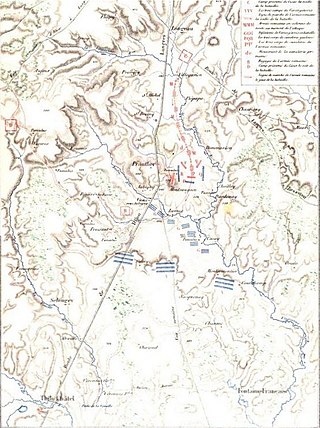

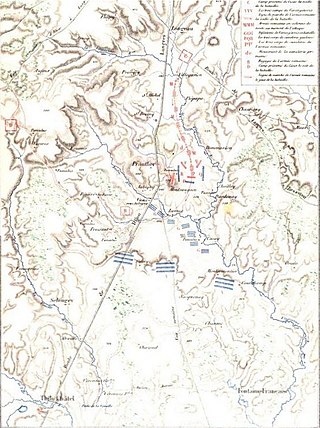

The Battle of Alesia or siege of Alesia was the climactic military engagement of the Gallic Wars, fought around the Gallic oppidum of Alesia in modern France, a major centre of the Mandubii tribe. It was fought by the Roman army of Julius Caesar against a confederation of Gallic tribes united under the leadership of Vercingetorix of the Arverni. It was the last major engagement between Gauls and Romans, and is considered one of Caesar's greatest military achievements and a classic example of siege warfare and investment; the Roman army built dual lines of fortifications—an inner wall to keep the besieged Gauls in, and an outer wall to keep the Gallic relief force out. The Battle of Alesia marked the end of Gallic independence in the modern day territory of France and Belgium.

The Cantiaci or Cantii were an Iron Age Celtic people living in Britain before the Roman conquest, and gave their name to a civitas of Roman Britain. They lived in the area now called Kent, in south-eastern England. Their capital was Durovernum Cantiacorum, now Canterbury.

The name France comes from Latin Francia.

Alesia was the capital of the Mandubii, one of the Gallic tribes allied with the Aedui. The Celtic oppidum was conquered by Julius Caesar during the Gallic Wars and afterwards became a Gallo-Roman town. Modern understanding of its location was controversial for a long time; however, it is now thought to have been located on Mont-Auxois, near Alise-Sainte-Reine in Burgundy, France.

In the course of his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar invaded Britain twice: in 55 and 54 BC. On the first occasion, Caesar took with him only two legions, and achieved little beyond a landing on the coast of Kent. The second invasion consisted of 800 ships, five legions and 2,000 cavalry. The force was so imposing that the Celtic Britons did not contest Caesar's landing, waiting instead until he began to move inland. Caesar eventually penetrated into Middlesex and crossed the Thames, forcing the British warlord Cassivellaunus to pay tribute to Rome and setting up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as a client king. The Romans then returned to Gaul without conquering any territory.

Chickens have been widely used as national symbols, and as mascots for clubs, businesses, and other associations.

The flag of Wallonia is a sub-national flag in Belgium that represents the Walloon Region and French Community. Designed in 1913, the flag depicts a red rooster, commonly known as the bold rooster or Walloon rooster, on a yellow field. The red and yellow coloring is historically associated with the city of Liège. The flag's association with Wallonia also mean that it is commonly used by the Walloon Movement.

The Gauls were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period. Their homeland was known as Gaul (Gallia). They spoke Gaulish, a continental Celtic language.

Gaius Valerius Troucillus or Procillus was a Helvian Celt who served as an interpreter and envoy for Julius Caesar in the first year of the Gallic Wars. Troucillus was a second-generation Roman citizen, and is one of the few ethnic Celts who can be identified both as a citizen and by affiliation with a Celtic polity. His father, Caburus, and a brother are named in Book 7 of Caesar's Bellum Gallicum as defenders of Helvian territory against a force sent by Vercingetorix in 52 BC. Troucillus plays a role in two episodes from the first book of Caesar's war commentaries, as an interpreter for the druid Diviciacus and as an envoy to the Suebian king Ariovistus, who accuses him of spying and has him thrown in chains.

The Helvii were a relatively small Celtic polity west of the Rhône river on the northern border of Gallia Narbonensis. Their territory was roughly equivalent to the Vivarais, in the modern French department of Ardèche. Alba Helviorum was their capital, possibly the Alba Augusta mentioned by Ptolemy, and usually identified with modern-day Alba-la-Romaine. In the 5th century the capital seems to have been moved to Viviers.

Galba was a king (rex) of the Suessiones, a Celtic polity of Belgic Gaul, during the Gallic Wars. When Julius Caesar entered the part of Gaul that was still independent of Roman rule in 58 BC, a number of Belgic polities formed a defensive alliance and acclaimed Galba commander-in-chief. Caesar recognizes Galba for his sense of justice (iustitia) and intelligence (prudentia).

The military campaigns of Julius Caesar were a series of wars that reshaped the political landscape of the Roman Republic, expanded its territories, and ultimately paved the way for the transition from republic to empire. The wars constituted both the Gallic Wars and Caesar's civil war.

National symbols of France are emblems of the French Republic and French people, and they are the cornerstone of the nation's republican tradition.

The Battle of Magetobriga was fought in 63 BC between rival tribes in Gaul. The Aedui tribe was defeated and massacred by the combined forces of their hereditary rivals, the Sequani and Arverni tribes. To secure their victory, the Sequani and Arverni enlisted the aid of the Germanic Suebi tribe led by its king Ariovistus, who would subsequently make increasingly imposing demands upon his Gallic allies. Following their defeat, the Aedui sent envoys to the Roman Senate, their traditional ally, seeking aid. The Roman general Julius Caesar would use the Aedui’s entrities and Ariovistus’ oppression as pretexts for launching his conquest of Gaul.

Founding of the Nation is a 1929 oil painting by Japanese yōga artist Kawamura Kiyoo (1854–1932). Based on the myth of the cave of the sun goddess from the Kojiki, the painting resides at the Musée Guimet in Paris, where it is known as Le coq blanc or The white cockerel.

There are numerous cultural references to chickens in myth, folklore, religion, and literature. Chickens are a sacred animal in many cultures and are deeply embedded in many belief systems and religious worship practices.

The Battle of the Vingeanne was mainly cavalry engagement between Roman legions, under the command of Gaius Julius Caesar and the coalition of Gaulic tribes led by Vercingetorix near the river of Vingeanne, as one of the major battles of the Gallic Wars. The battle was won by the Romans.