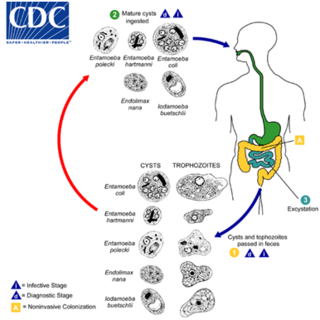

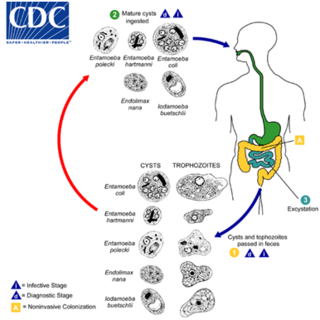

Entamoeba is a genus of Amoebozoa found as internal parasites or commensals of animals. In 1875, Fedor Lösch described the first proven case of amoebic dysentery in St. Petersburg, Russia. He referred to the amoeba he observed microscopically as Amoeba coli; however, it is not clear whether he was using this as a descriptive term or intended it as a formal taxonomic name. The genus Entamoeba was defined by Casagrandi and Barbagallo for the species Entamoeba coli, which is known to be a commensal organism. Lösch's organism was renamed Entamoeba histolytica by Fritz Schaudinn in 1903; he later died, in 1906, from a self-inflicted infection when studying this amoeba. For a time during the first half of the 20th century the entire genus Entamoeba was transferred to Endamoeba, a genus of amoebas infecting invertebrates about which little is known. This move was reversed by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in the late 1950s, and Entamoeba has stayed 'stable' ever since.

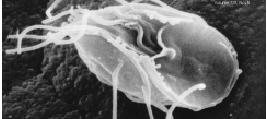

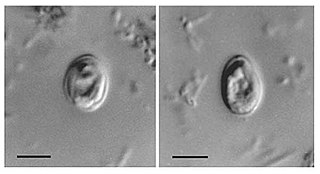

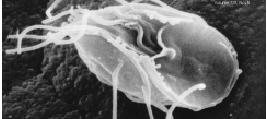

Giardia is a genus of anaerobic flagellated protozoan parasites of the phylum Metamonada that colonise and reproduce in the small intestines of several vertebrates, causing the disease giardiasis. Their life cycle alternates between a swimming trophozoite and an infective, resistant cyst. Giardia were first described by the Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1681. The genus is named after French zoologist Alfred Mathieu Giard.

Entamoeba histolytica is an anaerobic parasitic amoebozoan, part of the genus Entamoeba. Predominantly infecting humans and other primates causing amoebiasis, E. histolytica is estimated to infect about 35-50 million people worldwide. E. histolytica infection is estimated to kill more than 55,000 people each year. Previously, it was thought that 10% of the world population was infected, but these figures predate the recognition that at least 90% of these infections were due to a second species, E. dispar. Mammals such as dogs and cats can become infected transiently, but are not thought to contribute significantly to transmission.

Giardiasis is a parasitic disease caused by Giardia duodenalis. Infected individuals who experience symptoms may have diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Less common symptoms include vomiting and blood in the stool. Symptoms usually begin one to three weeks after exposure and, without treatment, may last two to six weeks or longer.

Trichomonas vaginalis is an anaerobic, flagellated protozoan parasite and the causative agent of a sexually transmitted disease called trichomoniasis. It is the most common pathogenic protozoan that infects humans in industrialized countries. Infection rates in men and women are similar but women are usually symptomatic, while infections in men are usually asymptomatic. Transmission usually occurs via direct, skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual, most often through vaginal intercourse. The WHO has estimated that 160 million cases of infection are acquired annually worldwide. The estimates for North America alone are between 5 and 8 million new infections each year, with an estimated rate of asymptomatic cases as high as 50%. Usually treatment consists of metronidazole and tinidazole.

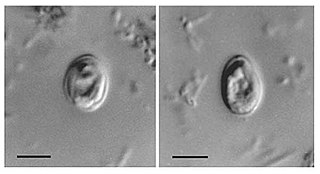

Entamoeba coli is a non-pathogenic species of Entamoeba that frequently exists as a commensal parasite in the human gastrointestinal tract. E. coli is important in medicine because it can be confused during microscopic examination of stained stool specimens with the pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica. This amoeba does not move much by the use of its pseudopod, and creates a "sur place (non-progressive) movement" inside the large intestine. Usually, the amoeba is immobile, and keeps its round shape. This amoeba, in its trophozoite stage, is only visible in fresh, unfixed stool specimens. Sometimes the Entamoeba coli have parasites as well. One is the fungus Sphaerita spp. This fungus lives in the cytoplasm of the E. coli. While this differentiation is typically done by visual examination of the parasitic cysts via light microscopy, new methods using molecular biology techniques have been developed. The scientific name of the amoeba, E. coli, is often mistaken for the bacterium, Escherichia coli. Unlike the bacterium, the amoeba is mostly harmless, and does not cause as many intestinal problems as some strains of the E. coli bacterium. To make the naming of these organisms less confusing, "alternate contractions" are used to name the species for the purpose making the naming easier; for example, using Esch. coli and Ent. coli for the bacterium and amoeba, instead of using E. coli for both.

The diplomonads are a group of flagellates, most of which are parasitic. They include Giardia duodenalis, which causes giardiasis in humans. They are placed among the metamonads, and appear to be particularly close relatives of the retortamonads.

A trophozoite is the activated, feeding stage in the life cycle of certain protozoa such as malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum and those of the Giardia group. The complementary form of the trophozoite state is the thick-walled cyst form. They are often different from the cyst stage, which is a protective, dormant form of the protozoa. Trophozoites are often found in the host's body fluids and tissues and in many cases, they are the form of the protozoan that causes disease in the host. In the protozoan, Entamoeba histolytica it invades the intestinal mucosa of its host, causing dysentery, which aid in the trophozoites traveling to the liver and leading to the production of hepatic abscesses.

Cryptosporidium, sometimes called crypto, is an apicomplexan genus of alveolates which are parasites that can cause a respiratory and gastrointestinal illness (cryptosporidiosis) that primarily involves watery diarrhea, sometimes with a persistent cough.

Retortamonas is a genus of flagellated excavates. It is one of only two genera belonging to the family Retortamonadidae along with the genus Chilomastix. The genus parasitizes a large range of hosts including humans. Species within this genus are considered harmless commensals which reside in the intestine of their host. The wide host diversity is a useful factor given that species are distinguished based on their host rather than morphology. This is because all species share similar morphology, which would present challenges when trying to make classifications based on structural anatomy. Although Retortamonas currently includes over 25 known species, it is possible that some defined species are synonymous, given that such overlapping species have been discovered in the past. Further efforts into learning about this genus must be done such as cross-transmission testing as well as biochemical and genetic studies. One of the most well-known species within this genus is Retortamonas intestinalis, a human parasite that lives in the large intestine of humans.

Dientamoebiasis is a medical condition caused by infection with Dientamoeba fragilis, a single-cell parasite that infects the lower gastrointestinal tract of humans. It is an important cause of traveler's diarrhea, chronic abdominal pain, chronic fatigue, and failure to thrive in children.

A mitosome is a mitochondrion-related organelle (MRO) found in a variety of parasitic unicellular eukaryotes, such as members of the supergroup Excavata. The mitosome was first discovered in 1999 in Entamoeba histolytica, an intestinal parasite of humans, and mitosomes have also been identified in several species of Microsporidia and in Giardia intestinalis.

Blastocystis is a genus of single-celled parasites belonging to the Stramenopiles that includes algae, diatoms, and water molds. There are several species, living in the gastrointestinal tracts of species as diverse as humans, farm animals, birds, rodents, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and cockroaches. Blastocystis has low host specificity, and many different species of Blastocystis can infect humans, and by current convention, any of these species would be identified as Blastocystis hominis.

The discovery of disease-causing pathogens is an important activity in the field of medical science. Many viruses, bacteria, protozoa, fungi, helminths, and prions are identified as a confirmed or potential pathogen. In the United States, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention program, begun in 1995, identified over a hundred patients with life-threatening illnesses that were considered to be of an infectious cause but that could not be linked to a known pathogen. The association of pathogens with disease can be a complex and controversial process, in some cases requiring decades or even centuries to achieve.

Protozoan infections are parasitic diseases caused by organisms formerly classified in the kingdom Protozoa. These organisms are now classified in the supergroups Excavata, Amoebozoa, Harosa, and Archaeplastida. They are usually contracted by either an insect vector or by contact with an infected substance or surface.

Spironucleus salmonicida is a species of fish parasite. It is a flagellate adapted to micro-aerobic environments that causes systemic infections in salmonid fish. The species creates foul-smelling, pus-filled abscesses in muscles and internal organs of aquarium fish. In the late 1980s when the disease was first reported, it was believed to be caused by Spironucleus barkhanus. Anders Jørgensen was the person that found out what species really caused the disease.

Spironucleus is a diplomonad genus that is bilaterally symmetrical and can be found in various animal hosts. This genus is a binucleate flagellate, which is able to live in the anaerobic conditions of animal intestinal tracts. A characteristic of Spironucleus that is common to all metamonads is that it does not have aerobic mitochondria, but instead rely on hydrogenosomes to produce energy. Spironucleus has six anterior and two posterior flagella. The life cycle of Spironucleus involves one active trophozoite stage and one inactive cyst stage. Spironucleus undergoes asexual reproduction via longitudinal binary fission. Spironucleusvortens can cause lateral line erosion in freshwater anglefish. Spironucleuscolumbae is found to cause hexamitiasis in pigeons. Finally, Spironucleusmuris is found to cause illnesses of the digestive system in mice, rats, and hamsters. The genome of Spironucleus has been studied to exhibit the role of lateral gene transfer from prokaryotes in allowing for anaerobic metabolic processes in diplomonads.

Amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery, is an infection of the intestines caused by a parasitic amoeba Entamoeba histolytica. Amoebiasis can be present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include lethargy, loss of weight, colonic ulcerations, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or bloody diarrhea. Complications can include inflammation and ulceration of the colon with tissue death or perforation, which may result in peritonitis. Anemia may develop due to prolonged gastric bleeding.

Dientamoeba fragilis is a species of single-celled excavates found in the gastrointestinal tract of some humans, pigs and gorillas. It causes gastrointestinal upset in some people, but not in others. It is an important cause of traveller's diarrhoea, chronic diarrhoea, fatigue and, in children, failure to thrive. Despite this, its role as a "commensal, pathobiont, or pathogen" is still debated. D. fragilis is one of the smaller parasites that are able to live in the human intestine. Dientamoeba fragilis cells are able to survive and move in fresh feces but are sensitive to aerobic environments. They dissociate when in contact or placed in saline, tap water or distilled water.

Chilomastix is a genus of pyriform excavates within the family Retortamonadidae All species within this genus are flagellated, structured with three flagella pointing anteriorly and a fourth contained within the feeding groove. Chilomastix also lacks Golgi apparatus and mitochondria but does possess a single nucleus. The genus parasitizes a wide range of vertebrate hosts, but is known to be typically non-pathogenic, and is therefore classified as harmless. The life cycle of Chilomastix lacks an intermediate host or vector. Chilomastix has a resistant cyst stage responsible for transmission and a trophozoite stage, which is recognized as the feeding stage. Chilomastix mesnili is one of the more studied species in this genus due to the fact it is a human parasite. Therefore, much of the information on this genus is based on what is known about this one species.