The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18. It was the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments adopted following the American Civil War.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Usually considered one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and equal protection under the law and was proposed in response to issues related to formerly enslaved Americans following the American Civil War. The amendment was bitterly contested, particularly by the states of the defeated Confederacy, which were forced to ratify it in order to regain representation in Congress. The amendment, particularly its first section, is one of the most litigated parts of the Constitution, forming the basis for landmark Supreme Court decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) regarding racial segregation, Loving v. Virginia (1967) regarding interracial marriage, Roe v. Wade (1973) regarding abortion, Bush v. Gore (2000) regarding the 2000 presidential election, Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) regarding same-sex marriage, and Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (2023) regarding race-based college admissions. The amendment limits the actions of all state and local officials, and also those acting on behalf of such officials.

Corporate personhood or juridical personality is the legal notion that a juridical person such as a corporation, separately from its associated human beings, has at least some of the legal rights and responsibilities enjoyed by natural persons. In most countries, a corporation has the same rights as a natural person to hold property, enter into contracts, and to sue or be sued.

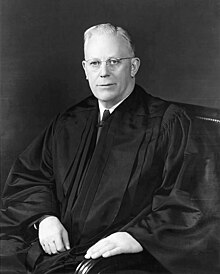

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. The decision partially overruled the Court's 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which had held that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that had come to be known as "separate but equal". The Court's unanimous decision in Brown, and its related cases, paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the civil rights movement, and a model for many future impact litigation cases.

A Congressional power of enforcement is included in a number of amendments to the United States Constitution. The language "The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation" is used, with slight variations, in Amendments XIII, XIV, XV, XIX, XXIII, XXIV, and XXVI.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision ruling that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that came to be known as "separate but equal". The decision legitimized the many state "Jim Crow laws" re-establishing racial segregation that had been passed in the American South after the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877. Such legally enforced segregation in the South lasted into the 1960s.

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States concerning the scope of Congress's power of enforcement under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The case also had a significant impact on historic preservation.

A Due Process Clause is found in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, which prohibit the deprivation of "life, liberty, or property" by the federal and state governments, respectively, without due process of law.

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." It mandates that individuals in similar situations be treated equally by the law.

In United States constitutional law, state action is an action by a person who is acting on behalf of a governmental body, and is therefore subject to limitations imposed on government by the United States Constitution, including the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments, which prohibit the federal and state governments from violating certain rights and freedoms.

The Privileges or Immunities Clause is Amendment XIV, Section 1, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution. Along with the rest of the Fourteenth Amendment, this clause became part of the Constitution on July 9, 1868.

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States regarding the power of Congress, pursuant to Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, to enact laws that enforce and interpret provisions of the Constitution.

In the United States, judicial review is the legal power of a court to determine if a statute, treaty, or administrative regulation contradicts or violates the provisions of existing law, a State Constitution, or ultimately the United States Constitution. While the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly define the power of judicial review, the authority for judicial review in the United States has been inferred from the structure, provisions, and history of the Constitution.

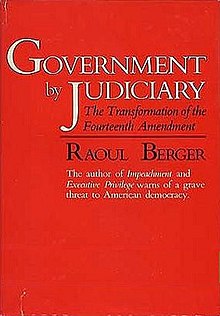

Raoul Berger was an American legal scholar at the University of California at Berkeley and Harvard Law School. While at Harvard, he was the Charles Warren Senior Fellow in American Legal History. He is known for his role in the development of originalism.

The Reconstruction Amendments, or the Civil War Amendments, are the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted between 1865 and 1870. The amendments were a part of the implementation of the Reconstruction of the American South which occurred after the Civil War.

Constitutional colorblindness is a legal and philosophical principle suggesting that the Constitution, particularly the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, should be interpreted as prohibiting the government from considering race in its laws, policies, or decisions. According to this doctrine, any use of racial classifications, whether intended to benefit or disadvantage certain groups, is viewed as inherently discriminatory and thus unconstitutional.

Melville Weston Fuller was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his tenure on the Supreme Court, exhibited by his tendency to support unfettered free enterprise and to oppose broad federal power. He wrote major opinions on the federal income tax, the Commerce Clause, and citizenship law, and he took part in important decisions about racial segregation and the liberty of contract. Those rulings often faced criticism in the decades during and after Fuller's tenure, and many were later overruled or abrogated. The legal academy has generally viewed Fuller negatively, although a revisionist minority has taken a more favorable view of his jurisprudence.

Hudson v. Palmer, 468 U.S. 517 (1984), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that prison inmates have no privacy rights in their cells protected by the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court also held that an intentional deprivation of property by a state employee "does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment if an adequate postdeprivation state remedy exists," extending Parratt v. Taylor to intentional torts.