The Pillar of Eliseg – also known as Elise's Pillar or Croes Elisedd in Welsh – stands near Valle Crucis Abbey, Denbighshire, Wales [Grid reference SJ 20267 44527]. It was erected by Cyngen ap Cadell, king of Powys in honour of his great-grandfather Elisedd ap Gwylog. The form Eliseg found on the pillar is assumed to be a mistake by the carver of the inscription.

Lachish was an ancient Canaanite and Israelite city in the Shephelah region of Israel, on the south bank of the Lakhish River, mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The current tell (ruin) by that name, known as Tel Lachish or Tell ed-Duweir, has been identified with the biblical Lachish. Today, it is an Israeli national park operated and maintained by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. It lies near the present-day moshav of Lakhish.

An abecedarium is an inscription consisting of the letters of an alphabet, almost always listed in order. Typically, abecedaria are practice exercises.

The Artognou stone, sometimes erroneously referred to as the Arthur stone, is an archaeological artefact uncovered in Cornwall in the United Kingdom. It was discovered in 1998 in securely dated sixth-century contexts among the ruins at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, a secular, high status settlement of sub-Roman Britain. It appears to have originally been a practice dedication stone for some building or other public structure, but it was broken in two and re-used as part of a drain when the original structure was destroyed. Upon its discovery the stone achieved some notoriety due to the suggestion that "Artognou" was connected to the legendary King Arthur, though scholars such as John Koch have criticized the evidence for this connection. The stone is on display at the Royal Cornwall Museum.

A number of pre-Columbian cultures in North America were collectively termed "Mound Builders", but the term has no formal meaning. It does not refer to a specific people or archaeological culture, but refers to the characteristic mound earthworks which indigenous peoples erected for an extended period of more than 5,000 years. The "Mound Builder" cultures span the period of roughly 3500 BCE to the 16th century CE, including the Archaic period, Woodland period, and Mississippian period. Geographically, the cultures were present in the region of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River Valley, and the Mississippi River Valley and its tributary waters.

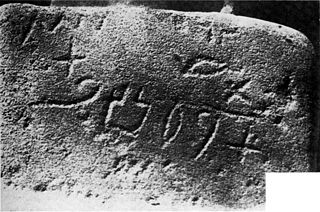

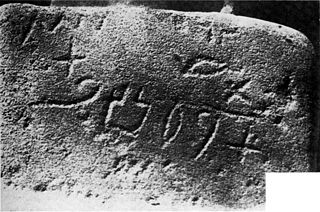

Proto-Sinaitic is found in a small corpus of c. 40 inscriptions and fragments, the vast majority from Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula, dating to the Middle Bronze Age. They are considered the earliest trace of alphabetic writing and the common ancestor of both the Ancient South Arabian script and the Phoenician alphabet, which led to many modern alphabets including the Greek alphabet. According to common theory, Canaanites or Hyksos who spoke a Proto-Semitic language repurposed Egyptian hieroglyphs to construct a different script.

The Criel Mound, also known as the South Charleston Mound, is a Native American burial mound located in South Charleston, West Virginia. It is one of the few surviving mounds of the Kanawha Valley Mounds that were probably built in the Woodland period after 500 B.C. The mound was built by the Adena culture, probably around 250–150 BC, and lay equidistant between two “sacred circles”, earthwork enclosures each 556 feet (169 m) in diameter. It was originally 33 feet (10 m) high and 173 feet (53 m) in diameter at the base, making it the second-largest such burial mound in the state of West Virginia. This archaeological site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Grave Creek Mound in the Ohio River Valley in West Virginia is one of the largest conical-type burial mounds in the United States, now standing 62 feet (19 m) high and 240 feet (73 m) in diameter. The builders of the site, members of the Adena culture, moved more than 60,000 tons of dirt to create it about 250–150 BC.

The Davenport Tablets are three inscribed slate tablets found in mounds near Davenport, Iowa on January 10, 1877, and January 30, 1878. If these tablets were real, they would have been proof for the argument that the people who built the Native American mounds, called the Mound Builders were built by an ancient race of settlers. The Davenport Tablets were originally considered authentic, though opinion shifted after 1885 and they are now considered a hoax.

George Hubbard Pepper was an American ethnologist and archaeologist. He worked on projects in New York, the Southwest and, most notably, the Nacoochee Mound in northeastern Georgia. His work with Frederick W. Hodge was sponsored by the Heye Foundation, Museum of the American Indian, and the Bureau of American Ethnology

The Bat Creek inscription is an inscribed stone tablet found by John W. Emmert on February 14, 1889. Emmert claimed to have found the tablet in Tipton Mound 3 during an excavation of Hopewell mounds in Loudon County, Tennessee. This excavation was part of a larger series of excavations that aimed to clarify the controversy regarding who is responsible for building the various mounds found in the Eastern United States.

Hanlin is a village near Shwebo in the Sagaing Division of Myanmar. In the era of the Pyu city-states it was a city of considerable significance, possibly a local capital replacing Sri Ksetra. Today the modest village is noted for its hot springs and archaeological sites. Hanlin, Beikthano, and Sri Ksetra, the ancient cities of the Pyu Kingdom were built on the irrigated fields of the dry zone of the Ayeyawady River basin. They were inscribed by UNESCO on its List of World Heritage Sites in Southeast Asia in May 2014 for their archaeological heritage traced back more than 1,000 years to between 200 BC and 900 AD.

Jagajjibanpur or Jagajivanpur is an archaeological site in Habibpur block of Malda district in West Bengal state in eastern India. This site is located at a distance of 41 km east from English Bazar town. The most significant findings from this site include a copper-plate inscription of Pala emperor Mahendrapaladeva and the structural remains of a 9th-century Buddhist Vihara: Nandadirghika-Udranga Mahavihara.

Bussell Island, formerly Lenoir Island, is an island located at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River, at its confluence with the Tennessee River in Loudon County, near the U.S. city of Lenoir City, Tennessee. The island was inhabited by various Native American cultures for thousands of years before the arrival of early European explorers. The Tellico Dam and a recreational area occupy part of the island. Part of the island was added in 1978 to the National Register of Historic Places for its archaeological potential.

Old Town is an archaeological site in Williamson County, Tennessee near Franklin. The site includes the remnants of a Native American village and mound complex of the Mississippian culture, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) as Old Town Archaeological Site (40WM2).

The Castalian Springs Mound State Historic Site (40SU14) is a Mississippian culture archaeological site located near the small unincorporated community of Castalian Springs in Sumner County, Tennessee. The site was first excavated in the 1890s and again as recently as the 2005 to 2011 archaeological field school led by Dr. Kevin E. Smith. A number of important finds have been associated with the site, most particularly several examples of Mississippian stone statuary and the Castalian Springs shell gorget held by the National Museum of the American Indian. The site is owned by the State of Tennessee and is a State Historic Site managed by the Bledsoe's Lick Association for the Tennessee Historical Commission. The site is not currently open to the public.

The Beasley Mounds Site (40SM43) is a Mississippian culture archaeological site located at the confluence of Dixon Creek and the Cumberland River near the unincorporated community of Dixon Springs in Smith County, Tennessee. The site was first excavated by amateur archaeologists in the 1890s. More examples of Mississippian stone statuary have been found at the site than any other in the Middle Tennessee area. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010.

Stone box graves were a method of burial used by Native Americans of the Mississippian culture in the Midwestern United States and the Southeastern United States. Their construction was especially common in the Cumberland River Basin, in settlements found around present-day Nashville, Tennessee.

Fewkes Group Archaeological Site, also known as the Boiling Springs Site, is a pre American history Native American archaeological site located in the city of Brentwood, in Williamson County, Tennessee. It is in Primm Historic Park on the grounds of Boiling Spring Academy, a historic schoolhouse established in 1830. The 15-acre site consists of the remains of a late Mississippian culture mound complex and village roughly dating to 1050-1475 AD. The site, which sits on the western bank of the Little Harpeth River, has five mounds, some used for burial and others, including the largest, were ceremonial platform mounds. The village was abandoned for unknown reasons around 1450. The site is named in honor of Dr. J. Walter Fewkes, the Chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1920, who had visited the site and recognized its potential. While it was partially excavated by the landowner in 1895, archaeologist William E. Myer directed a second, more thorough excavation in October 1920. The report of his findings was published in the Bureau of American Ethnology's Forty-First Annual Report. Many of the artifacts recovered from the site are now housed at the Smithsonian Institution. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 21, 1980, as NRIS number 80003880.

The McMahan Mound Site (40SV1), also known as McMahan Indian Mound, is an archaeological site located in Sevierville, Tennessee just above the confluence of the West Fork and the Little Pigeon rivers in Sevier County.