The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan (or Teotihuacan Spider Woman) is a proposed goddess of the pre-Columbian Teotihuacan civilization (ca. 100 BCE - 700 CE), in what is now Mexico.

The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan (or Teotihuacan Spider Woman) is a proposed goddess of the pre-Columbian Teotihuacan civilization (ca. 100 BCE - 700 CE), in what is now Mexico.

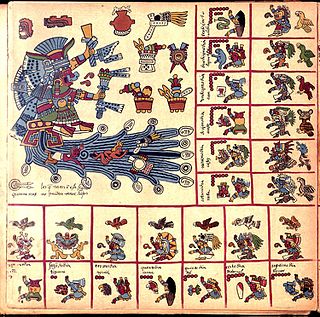

In years leading up to 1942, a series of murals were found in the Tepantitla compound in Teotihuacan. The Tepantitla compound provided housing for what appears to have been high status citizens and its walls (as well as much of Teotihuacan) are adorned with brightly painted frescoes. The largest figures within the murals depicted complex and ornate deities or supernaturals. In 1942, archaeologist Alfonso Caso identified these central figures as a Teotihuacan equivalent of Tlaloc, the Mesoamerican god of rain and warfare. This was the consensus view for some 30 years.

In 1974, Peter Furst suggested that the murals instead showed a feminine deity, an interpretation echoed by researcher Esther Pasztory. Their analysis of the murals was based on a number of factors including the gender of accompanying figures, the green bird in the headdress, and the spiders seen above the figure. [1] Pasztory concluded that the figures represented a vegetation and fertility goddess that was a predecessor of the much later Aztec goddess Xochiquetzal. In 1983, Karl Taube termed this goddess the "Teotihuacan Spider Woman". The more neutral description of this deity as the "Great Goddess" has since gained currency.

The Great Goddess has since been identified at Teotihuacan locations other than Tepantitla – including the Tetitla compound (see photo below), the Palace of the Jaguars, and the Temple of Agriculture – as well as on portable art including vessels [2] and even on the back of a pyrite mirror. [3] The 3-metre-high blocky statue (see photo below) which formerly sat near the base of the Pyramid of Moon is thought to represent the Great Goddess, [4] despite the absence of the bird-headdress or the fanged nosepiece. [5]

Esther Pasztory speculates that the Great Goddess, as a distant and ambivalent mother figure, was able to provide a uniting structure for Teotihuacan that transcended divisions within the city. [6]

The Great Goddess is apparently peculiar to Teotihuacan, and does not appear outside the city except where Teotihuacanos settled. [7] There is very little trace of the Great Goddess in the Valley of Mexico's later Toltec culture, although an earth goddess image has been identified on Stela 1, from Xochicalco, a Toltec contemporary. [8] While the Aztec goddess Chalchiuhtlicue has been identified as a successor to the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan, archaeologist Janet Catherine Berlo has suggested that at least the Goddess' warlike aspect was assumed by the Aztec's protector god – and war god – Huītzilōpōchtli. The wresting of this aspect from the Great Goddess was memorialized in the myth Huitzilopochtli, who slew his sister Coyolxauhqui shortly after his birth. [9]

Berlo also sees echoes of the Great Goddess in the veneration of the Virgin of Guadalupe. [8]

Defining characteristics of the Great Goddess are a bird headress and a nose pendant with descending fangs. [10] In the Tepantitla and Tetitla murals, for example, the Great Goddess wears a frame headdress that includes the face of a green bird, generally identified as an owl or quetzal, [11] and a rectangular nosepiece adorned with three circles below which hang three or five fangs. The outer fangs curl away from the center, while the middle fang points down. She is also always seen with jewelry such as beaded necklaces and earrings which were commonly worn by Teotihuacan women. Her face is always shown frontally, either masked or partially covered, and her hands in murals are always depicted stretched out giving water, seeds, and jade treasures. [12]

Other defining characteristics include the colors red and yellow; [13] note that the Goddess appears with a yellowish cast in both murals.

In the depiction from the Tepantitla compound, the Great Goddess appears with vegetation growing out of her head, perhaps hallucinogenic morning glory vines [14] or the world tree. [15] Spiders and butterflies appear on the vegetation and water drips from its branches and flows from the hands of the Great Goddess. Water also flows from her lower body. These many representations of water led Caso to declare this to be a representation of the rain god, Tlaloc.

Below this depiction, separated from it by two interwoven serpents and a talud-tablero, is a scene showing dozens of small human figures, usually wearing only a loincloth and often showing a speech scroll (see photo below). Several of these figures are swimming in the criss-crossed rivers flowing from a mountain at the bottom of the scene. Caso interpreted this scene as the afterlife realm of Tlaloc, although this interpretation has also been challenged, most recently by María Teresa Uriarte, who provides a more commonplace interpretation: that "this mural represents Teotihuacan as [the] prototypical civilized city associated with the beginning of time and the calendar". [16]

The Great Goddess is thought to have been a goddess of the underworld, darkness, the earth, water, war, and possibly even creation itself. To the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica, the jaguar, the owl, and especially the spider were considered creatures of darkness, often found in caves and during the night. The fact that the Great Goddess is frequently depicted with all of these creatures further supports the idea of her underworld connections.[ citation needed ]

In many murals, the Great Goddess is shown with many of the scurrying arachnids in the background, on her clothing, or hanging from her arms. She is often seen with shields decorated with spider webs, further suggesting her relationship with warfare. The Great Goddess is often shown in paradisial settings, giving gifts. [17] For example, the mural from Tepantitla shows water dripping from her hands while in the tableau under her portrait mortals swim, play ball, and dance (see photo to right). This seeming gentleness is in contrast to later similar Aztec deities such as Cihuacoatl, who frequently has a warlike aspect. [18] This contrast, according to Esther Pasztory, an archaeologist who has long studied Teotihuacan, extends beyond the goddesses in question to the core of the Teotihuacan and Aztec cultures themselves: "Although I cannot prove this precisely, I sense that the Aztec goal was military glory and staving off the collapse of the universe, whereas the Teotihuacan aim seems to have been the creation of paradise on earth." [19]

This is not to say, however, that the Great Goddess does not have her more violent aspect: one mural fragment, likely from Techinantitla, shows her as a large mouth with teeth, framed by clawed hands. [20]

Elisa C. Mandell's 2015 article "A New Analysis of the Gender Attribution of the 'Great Goddess' of Teotihuacan" [21] published by Cambridge challenges the interpretation of the Great Goddess as being not only female but also male, a mixed-gender figure. Sex is understood as the biological and anatomical difference between men and women, while gender is a socially and culturally constructed identity. There are disagreements among historians over the role of biology to informing gender and “whether sex as a biological concept exists outside Western society”. [22] There is a history of mixed-gender identity within Mesoamerican people, and considering that the Goddess is from Teotihuacan, Western models of gender binary should not be imposed upon non-Western figures. Additionally, there are no explicit sexual characteristics shown on the Great Goddess so their sex cannot be deduced. [21]

There is a history of masculine and feminine attributes being shown within the same figure in Mesoamerican art. The Maya Maize Deity can be seen as an example of this, as posited by Bassie-Sweet. Considering the importance of maize, or corn, which has the ability to switch between the two biological sexes. With the fact that Mesoamerican people considered themselves to be descendants of the corn plant, this nature based culture allows for ambiguity of sex and gender within the peoples. [23] Furthermore, we have evidence that the Maize God inspired Maya elites, no matter their gender, to wear mixed-gender costumes to honor the Maize God. [24]

Mandell's article analyzes and reattributes each element included in the Goddesses depiction in the Tepantitla and Tetitla murals, reconsidering previous gendering of these elements. Pasztory references the three main elements of the Goddess: the avian headdress, the yellow and red zig-zags, and the nosebar. [25] Mandell references many depictions of male and female deities where these elements are including, suggesting that it is impossible to determine any specific gendering from the headdress, zig-zags, and nosebar. Mandell then suggests that the mixture of these male and female attributes suggests that the Goddess is mixed-gender.

More generally, many images have been understood as depicting the Goddess because of their inclusion of water, which is also understood as a feminine symbol. Mandell posits that there is nothing inherently feminine about this liquid. [21] In the Tepantitla and Tetitla murals, the water is filled with seed and shell shaped object. Liquid with sea-life and sperm may represent semen made up of sperm, thus suggesting a masculine association. One of the reasons Pasztory had asserted that the Goddess was a feminine deity is because it was understood to be wearing a quechquemitl. [25] The quechquemitl is often associated with female figures. However, the triangular shirt or cape had multiple meanings for different people that also changed over time, [26] and therefore it cannot be used as a simple demarcation of a figure’s sex or gender. Similarly, the Goddess’ ear ornaments had been a factor in deciphering the deity as feminine. Mandell asserts that there is no conclusive evidence to support these ornaments as feminine, and rather this particular ear ornament has been seen on male and female gods. The short skirt seen worn by figures in the Tepantitla mural has been considered another attribute of femininity, yet in Teotihuacan it was more common for males to be depicted in short kilts. [27] The profile figures in the Tepantitla mural carry small bags, which men are known to carry, as seen in depictions of priests in Maya art. Mandell asserts that the ambiguity and combination of masculine and feminine attributes should be seen as a mixed-gender performance, not subjected to the Western binary model of gender. [21]

Some American Indians, such as the Pueblo and Navajo, revered what seems to be a similar deity. Referred to as the Spider Grandmother, she shares many traits with the Teotihuacan Spider Woman.

Tláloc is the god of rain in Aztec religion. He was also a deity of earthly fertility and water, worshipped as a giver of life and sustenance. This came to be due to many rituals, and sacrifices that were held in his name. He was feared, but not maliciously, for his power over hail, thunder, lightning, and even rain. He is also associated with caves, springs, and mountains, most specifically the sacred mountain where he was believed to reside. Cerro Tláloc is very important in understanding how rituals surrounding this deity played out. His followers were one of the oldest and most universal in ancient Mexico.

A chacmool is a form of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing 90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach. These figures possibly symbolised slain warriors carrying offerings to the gods; the bowl upon the chest was used to hold sacrificial offerings, including pulque, tamales, tortillas, tobacco, turkeys, feathers, and incense. In Aztec examples, the receptacle is a cuauhxicalli. Chacmools were often associated with sacrificial stones or thrones. The chacmool form of sculpture first appeared around the 9th century AD in the Valley of Mexico and the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

Teotihuacan is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, 40 kilometers (25 mi) northeast of modern-day Mexico City.

Chalchiuhtlicue is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalchiuhtlicue is associated with fertility, and she is the patroness of childbirth. Chalchiuhtlicue was highly revered in Aztec culture at the time of the Spanish conquest, and she was an important deity figure in the Postclassic Aztec realm of central Mexico. Chalchiuhtlicue belongs to a larger group of Aztec rain gods, and she is closely related to another Aztec water god called Chalchiuhtlatonal.

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played since at least 1650 BC by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modernized version of the game, ulama, is still played by the indigenous populations in some places.

K’uk’ulkan, also spelled Kukulkan, is the serpent deity of Maya mythology. It is closely related to the deity Qʼuqʼumatz of the Kʼicheʼ people and to Quetzalcoatl of Aztec mythology. Prominent temples to Kukulkan are found at archaeological sites in the Yucatán Peninsula, such as Chichen Itza, Uxmal and Mayapan.

Pre-Columbian art refers to the visual arts of indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, North, Central, and South Americas from at least 13,000 BCE to the European conquests starting in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Pre-Columbian era continued for a time after these in many places, or had a transitional phase afterwards. Many types of perishable artifacts that were once very common, such as woven textiles, typically have not been preserved, but Precolumbian monumental sculpture, metalwork in gold, pottery, and painting on ceramics, walls, and rocks have survived more frequently.

The Wagner Murals are the name for over 70 mural fragments illegally removed from the Pre-Columbian site of Teotihuacán in the 1960s.

World trees are a prevalent motif occurring in the mythical cosmologies, creation accounts, and iconographies of the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica. In the Mesoamerican context, world trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which also serve to represent the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi which connects the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial realm.

Mesoamerican architecture is the set of architectural traditions produced by pre-Columbian cultures and civilizations of Mesoamerica, traditions which are best known in the form of public, ceremonial and urban monumental buildings and structures. The distinctive features of Mesoamerican architecture encompass a number of different regional and historical styles, which however are significantly interrelated. These styles developed throughout the different phases of Mesoamerican history as a result of the intensive cultural exchange between the different cultures of the Mesoamerican culture area through thousands of years. Mesoamerican architecture is mostly noted for its pyramids, which are the largest such structures outside of Ancient Egypt.

Like other Mesoamerican peoples, the traditional Maya recognize in their staple crop, maize, a vital force with which they strongly identify. This is clearly shown by their mythological traditions. According to the 16th-century Popol Vuh, the Hero Twins have maize plants for alter egos and man himself is created from maize. The discovery and opening of the Maize Mountain – the place where the corn seeds are hidden – is still one of the most popular of Maya tales. In the Classic period, the maize deity shows aspects of a culture hero.

The Feathered Serpent is a prominent supernatural entity or deity, found in many Mesoamerican religions. It is still called Quetzalcoatl among the Aztecs, Kukulkan among the Yucatec Maya, and Q'uq'umatz and Tohil among the K'iche' Maya.

Classic Veracruz culture refers to a cultural area in the north and central areas of the present-day Mexican state of Veracruz, a culture that existed from roughly 100 to 1000 CE, or during the Classic era.

Ancient Mesoamericans were the first people to invent rubber balls, sometime before 1600 BCE, and used them in a variety of roles. The Mesoamerican ballgame, for example, employed various sizes of solid rubber balls and balls were burned as offerings in temples, buried in votive deposits, and laid in sacred bogs and cenotes.

Janet Catherine Berlo is an American art historian and academic, noted for her publications and research into the visual arts heritage of Native American and pre-Columbian cultures. She has also published and lectured on gender studies, the representation and participation of women in indigenous and visual arts, the history of graphic arts since the mid-19th century, indigenous textile arts, and American quilting history and traditions. In the early portion of her academic career Berlo made notable contributions towards the understanding of the art and iconography of Mesoamerica, in particular that of the Classic-period Teotihuacan civilization. Since 2003 Berlo has held the position of Professor of Art History and Visual and Cultural Studies at the Department of Art and Art History, University of Rochester, New York.

In Mesoamerican culture, Tonatiuh is an Aztec sun deity of the daytime sky who rules the cardinal direction of east. According to Aztec Mythology, Tonatiuh was known as "The Fifth Sun" and was given a calendar name of naui olin, which means "4 Movement". Represented as a fierce and warlike god, he is first seen in Early Postclassic art of the Pre-Columbian civilization known as the Toltec. Tonatiuh's symbolic association with the eagle alludes to the Aztec belief of his journey as the present sun, travelling across the sky each day, where he descended in the west and ascended in the east. It was thought that his journey was sustained by the daily sacrifice of humans. His Nahuatl name can also be translated to "He Who Goes Forth Shining" or "He Who Makes The Day." Tonatiuh was thought to be the central deity on the Aztec calendar stone but is no longer identified as such. In Toltec culture, Tonatiuh is often associated with Quetzalcoatl in his manifestation as the morning star aspect of the planet Venus.

Painting in the Americas before European colonization is the Precolumbian painting traditions of the Americas. Painting was a relatively widespread, popular and diverse means of communication and expression for both religious and utilitarian purpose throughout the regions of the Western Hemisphere. During the period before and after European exploration and settlement of the Americas; including North America, Central America, South America and the islands of the Caribbean, the Bahamas, the West Indies, the Antilles, the Lesser Antilles and other island groups, indigenous native cultures produced a wide variety of visual arts, including painting on textiles, hides, rock and cave surfaces, bodies especially faces, ceramics, architectural features including interior murals, wood panels, and other available surfaces. Many of the perishable surfaces, such as woven textiles, typically have not been preserved, but Precolumbian painting on ceramics, walls, and rocks have survived more frequently.

Esther Pasztory is a professor emerita of Pre-Columbian art history at Columbia University. From 1997 to her retirement in 2013 she held the Lisa and Bernard Selz Chair in Art History and Archaeology. Among her many publications are the first art historical manuscripts on Teotihuacan and the Aztecs. She has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship (1987–88) and a senior fellow of the board of Dumbarton Oaks.

The use of mirrors in Mesoamerican culture was associated with the idea that they served as portals to a realm that could be seen but not interacted with. Mirrors in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from the decorative to the divinatory. An ancient tradition among many Mesoamerican cultures was the practice of divination using the surface of a bowl of water as a mirror. At the time of the Spanish conquest this form of divination was still practiced among the Maya, Aztecs and Purépecha. In Mesoamerican art, mirrors are frequently associated with pools of liquid; this liquid was likely to have been water.

The use of serpents in Aztec art ranges greatly from being an inclusion in the iconography of important religious figures such as Quetzalcoatl and Cōātlīcue, to being used as symbols on Aztec ritual objects, and decorative stand-alone representations which adorned the walls of monuments such as the Templo Mayor.