The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace of Versailles, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which led to the war. The other Central Powers on the German side signed separate treaties. The United States never ratified the Versailles treaty and made a separate peace treaty with Germany. Although the armistice of 11 November 1918 ended the actual fighting, it took six months of Allied negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty. Germany was not allowed to participate in the negotiations; it was forced to sign the final treaty.

Following the ratification of article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles at the conclusion of World War I, the Central Powers were made to give war reparations to the Allied Powers. Each defeated power was required to make payments in either cash or kind. Because of the financial situation in Austria, Hungary, and Turkey after the war, few to no reparations were paid and the requirements for reparations were cancelled. Bulgaria, having paid only a fraction of what was required, saw its reparation figure reduced and then cancelled. Historians have recognized the German requirement to pay reparations as the "chief battleground of the post-war era" and "the focus of the power struggle between France and Germany over whether the Versailles Treaty was to be enforced or revised."

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is an international financial institution which is owned by member central banks. Its primary goal is to foster international monetary and financial cooperation while serving as a bank for central banks. With its establishment in 1929, its initial purpose was to oversee the settlement of World War I war reparations.

Gustav Ernst Stresemann was a German statesman who served as chancellor of Germany from August to November 1923, and as foreign minister from 1923 to 1929. His most notable achievement was the reconciliation between Germany and France, for which he and French Prime Minister Aristide Briand received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926. During a period of political instability and fragile, short-lived governments, Stresemann was the most influential politician in most of the Weimar Republic's existence.

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

The Locarno Treaties were seven agreements negotiated in Locarno, Switzerland, from 5 to 16 October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central and Eastern Europe sought to secure the post-war territorial settlement, in return for normalizing relations with the defeated German Reich. It also stated that Germany would never go to war with the other countries. Locarno divided borders in Europe into two categories: western, which were guaranteed by the Locarno Treaties, and eastern borders of Germany with Poland, which were open for revision.

Hjalmar Schacht was a German economist, banker, centre-right politician, and co-founder of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner and President of the Reichsbank under the Weimar Republic. He was a fierce critic of his country's post-World War I reparations obligations. He was also central in helping create the group of German industrialists and landowners that pushed Hindenburg to appoint the first NSDAP-led government.

Events in the year 1921 in Germany.

Events from the year 1922 in France.

The Dawes Plan temporarily resolved the issue of the reparations that Germany owed to the Allies of World War I. Enacted in 1924, it ended the crisis in European diplomacy that occurred after French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr in response to Germany's failure to meet its reparations obligations.

The Young Plan was a 1929 attempt to settle issues surrounding the World War I reparations obligations that Germany owed under the terms of Treaty of Versailles. Developed to replace the 1924 Dawes Plan, the Young Plan was negotiated in Paris from February to June 1929 by a committee of international financial experts under the leadership of American businessman and economist Owen D. Young. Representatives of the affected governments then finalised and approved the plan at The Hague conference of 1929/30. Reparations were set at 36 billion Reichsmarks payable through 1988. Including interest, the total came to 112 billion Reichsmarks. The average annual payment was approximately two billion Reichsmarks. The plan came into effect on 17 May 1930, retroactive to 1 September 1929.

Julius Curtius was a German politician who served as Minister for Economic Affairs and Foreign Minister of the Weimar Republic.

The Occupation of the Ruhr was a period of military occupation of the Ruhr region of Germany by France and Belgium from 11 January 1923 to 25 August 1925.

The Lausanne Conference of 1932, held from 16 June to 9 July 1932 in Lausanne, Switzerland, was a meeting of representatives from the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Belgium, Japan and Germany that resulted in an agreement to lower Germany's World War I reparations obligations as imposed by the Treaty of Versailles and the 1929 Young Plan. The reduction of approximately 90 per cent was made as a result of the difficult economic circumstances during the Great Depression. The Lausanne Treaty never came into effect because it was dependent on an agreement with the United States on the repayment of the loans it had made to the Allied powers during World War I, and that agreement was never reached. The Lausanne Conference marked the de facto end of Germany's reparations payments until after World War II.

MEFO was the more common abbreviation for German: MEtallurgische FOrschungsgesellschaft m.b.H., a dummy company set up by the Nazi German government to finance the German re-armament effort in the years prior to World War II.

The Occupation of the Rhineland placed the region of Germany west of the Rhine river and four bridgeheads to its east under the control of the victorious Allies of World War I from 1 December 1918 until 30 June 1930. The occupation was imposed and regulated by articles in the Armistice of 11 November 1918, the Treaty of Versailles and the parallel agreement on the Rhineland occupation signed at the same time as the Versailles Treaty. The Rhineland was demilitarised, as was an area stretching fifty kilometres east of the Rhine, and put under the control of the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission, which was led by a French commissioner and had one member each from Belgium, Great Britain and the United States. The purpose of the occupation was to give France and Belgium security against any future German attack and serve as a guarantee for Germany's reparations obligations. After Germany fell behind on its payments in 1922, the occupation was expanded to include the industrial Ruhr valley from 1923 to 1925.

Hyperinflation affected the German Papiermark, the currency of the Weimar Republic, between 1921 and 1923, primarily in 1923. It caused considerable internal political instability in the country and led to the occupation of the Ruhr by France and Belgium after Germany defaulted on its war reparations.

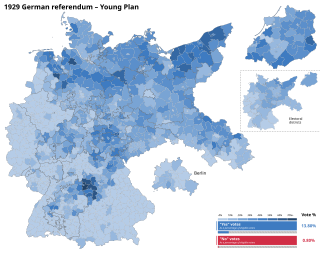

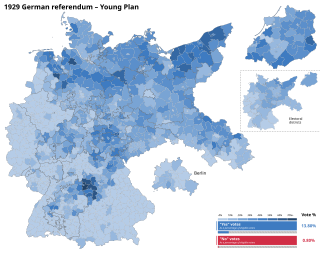

The 1929 German Referendum was an attempt during the Weimar Republic to use popular legislation to annul the agreement in the Young Plan between the German government and the World War I opponents of the German Reich regarding the amount and conditions of reparations payments. The referendum was the result of the initiative "Against the Enslavement of the German People " launched in 1929 by right-wing parties and organizations. It called for an overall revision of the Treaty of Versailles and stipulated that government officials who accepted new reparation obligations would be committing treason.

After World War II both West Germany and East Germany were obliged to pay war reparations to the Allied governments, according to the Potsdam Conference. Other Axis nations were obliged to pay war reparations according to the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947. Austria was not included in any of these treaties.

The Mellon-Berenger Agreement was an agreement on the amount and rate of repayment of France's debt to the United States arising from loans and payments in kind made during World War I (1914–1918), both before and after the armistice with Germany. The agreement greatly reduced the amount owing by France, with relatively easy payment terms. However, it was deeply unpopular in France, whose people felt that the United States should waive the debt in light of the huge losses of life and material damage that France had suffered, or at least link payments to reparations from Germany. Ratification by the French parliament was delayed until July 1929. The Great Depression began soon after. In the end, little of the debt was repaid.