Haida are an Indigenous group who have traditionally occupied Haida Gwaii, an archipelago just off the coast of British Columbia, Canada, for at least 12,500 years.

Totem poles are monumental carvings found in western Canada and the northwestern United States. They are a type of Northwest Coast art, consisting of poles, posts or pillars, carved with symbols or figures. They are usually made from large trees, mostly western red cedar, by First Nations and Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast including northern Northwest Coast Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian communities in Southeast Alaska and British Columbia, Kwakwaka'wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth communities in southern British Columbia, and the Coast Salish communities in Washington and British Columbia.

Wood carving is a form of woodworking by means of a cutting tool (knife) in one hand or a chisel by two hands or with one hand on a chisel and one hand on a mallet, resulting in a wooden figure or figurine, or in the sculptural ornamentation of a wooden object. The phrase may also refer to the finished product, from individual sculptures to hand-worked mouldings composing part of a tracery.

A netsuke is a miniature sculpture, originating in 17th century Japan. Initially a simply-carved button fastener on the cords of an inrō box, netsuke later developed into ornately sculpted objects of craftsmanship.

Charles Marius Barbeau,, also known as C. Marius Barbeau, or more commonly simply Marius Barbeau, was a Canadian ethnographer and folklorist who is today considered a founder of Canadian anthropology. A Rhodes Scholar, he is best known for an early championing of Québecois folk culture, and for his exhaustive cataloguing of the social organization, narrative and musical traditions, and plastic arts of the Tsimshianic-speaking peoples in British Columbia, and other Northwest Coast peoples. He developed unconventional theories about the peopling of the Americas.

Argillite is a fine-grained sedimentary rock composed predominantly of indurated clay particles. Argillaceous rocks are basically lithified muds and oozes. They contain variable amounts of silt-sized particles. The argillites grade into shale when the fissile layering typical of shale is developed. Another name for poorly lithified argillites is mudstone. These rocks, although variable in composition, are typically high in aluminium and silica with variable alkali and alkaline earth cations. The term pelitic or pelite is often applied to these sediments and rocks. Metamorphism of argillites produces slate, phyllite, and pelitic schist.

Wilson Duff was a Canadian archaeologist, cultural anthropologist, and museum curator.

Charles Edenshaw was a Haida artist from Haida Gwaii, British Columbia. He is known for his woodcarving, argillite carving, jewellery, and painting. His style was known for its originality and innovative narrative forms, created while adhering to the principles of formline art characteristic of Haida art. In 1902, the ethnographer and collector Charles F. Newcombe called Edenshaw “the best carver in wood and stone now living.”

Northwest Coast art is the term commonly applied to a style of art created primarily by artists from Tlingit, Haida, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka'wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth and other First Nations and Native American tribes of the Northwest Coast of North America, from pre-European-contact times up to the present.

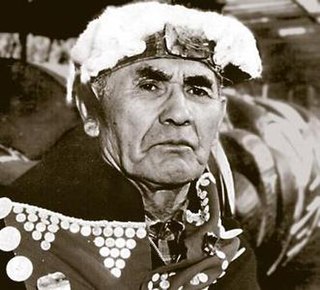

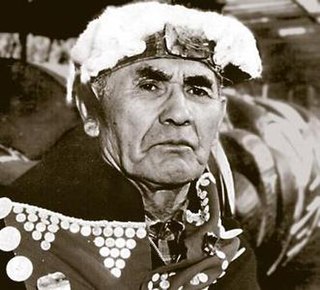

Chief Mungo Martin or Nakapenkem, Datsa, was an important figure in Northwest Coast style art, specifically that of the Kwakwaka'wakw Aboriginal people who live in the area of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. He was a major contributor to Kwakwaka'wakw art, especially in the realm of wood sculpture and painting. He was also known as a singer and songwriter.

David A. Boxley is an American artist from the Tsimshian tribe in Alaska, most known for his prolific creation of Totem Poles and other Tsimshian artworks.

Inuit art, also known as Eskimo art, refers to artwork produced by Inuit, that is, the people of the Arctic previously known as Eskimos, a term that is now often considered offensive. Historically, their preferred medium was walrus ivory, but since the establishment of southern markets for Inuit art in 1945, prints and figurative works carved in relatively soft stone such as soapstone, serpentinite, or argillite have also become popular.

SG̱ang Gwaay Llnagaay, commonly known by its English name Ninstints, is a village site of the Haida people and part of the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site on Haida Gwaii on the North Coast of British Columbia, Canada.

The visual arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas encompasses the visual artistic practices of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from ancient times to the present. These include works from South America and North America, which includes Central America and Greenland. The Siberian Yupiit, who have great cultural overlap with Native Alaskan Yupiit, are also included.

Toi whakairo or just whakairo (carving) is a Māori traditional art of carving in wood, stone or bone.

Formline art is a feature in the indigenous art of the Northwest Coast of North America, distinguished by the use of characteristic shapes referred to as ovoids, U forms and S forms. Coined by Bill Holm in his 1965 book Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form, the "formline is the primary design element on which Northwest Coast art depends, and by the turn of the 20th century, its use spread to the southern regions as well. It is the positive delineating force of the painting, relief and engraving. Formlines are continuous, flowing, curvilinear lines that turn, swell and diminish in a prescribed manner. They are used for figure outlines, internal design elements and in abstract compositions."

The Nisga'a and Haida Crest Poles of the Royal Ontario Museum are a collection of four large totem poles, hand carved from western red cedar by the Nisga’a people and Haida people of British Columbia's coast. The poles are referred to as: Three Persons Along (Nisga'a); the Pole of Sag̱aw̓een (Nisga'a); the Shaking Pole of Kw’ax̱suu (Nisga'a); and House 16: Strong House Pole (Haida). Each of the crest poles tell a family story, as carved figures represent crests that commemorate family history by describing family origins, achievements and experiences. These memorial poles were typically placed in front of the owners' house along the beach.

The Haida Heritage Centre is the premier cultural centre and museum of the Haida people. It is located in Skidegate, a community on Graham Island in Haida Gwaii off the Pacific coast of British Columbia, Canada. The centre is situated just south of the site of a historical village in Kay Llnagaay. The Centre was built and is managed by Gwaalagaa Naay, an economic development branch of the Skidegate Band Council, the owners of the site. It is one of the major aboriginal cultural tourism attractions in Haida Gwaii and has been described as "a place for the Haida voice to be heard." Educational programs are offered in partnership with School District 50 Haida Gwaii, the University of Northern British Columbia, and with the Haida Gwaii Higher Education Society.

Bambooworking is the activity or skill of making items from bamboo, and includes architecture, carpentry, furniture and cabinetry, carving, joinery, and weaving. Its historical roots in Asia span cultures, civilizations, and millennia, and is found across East, South, and Southeast Asia.

Kiusta located on Haida Gwaii is the oldest Northern Haida village: and the site of first recorded contact between the Haida and Europeans in 1774. Haida lived in this village for thousands of years, due to the sheltered nature of its location it was used for boats offloading, especially in rough waters. Kiusta is one of the oldest archeological sites of human use in British Columbia, and continues to be a site for cultural revitalisation.