Chaldea was a small country that existed between the late 10th or early 9th and mid-6th centuries BC, after which the country and its people were absorbed and assimilated into the indigenous population of Babylonia. Semitic-speaking, it was located in the marshy land of the far southeastern corner of Mesopotamia and briefly came to rule Babylon. The Hebrew Bible uses the term כשדים (Kaśdim) and this is translated as Chaldaeans in the Greek Old Testament, although there is some dispute as to whether Kasdim in fact means Chaldean or refers to the south Mesopotamian Kaldu.

Nineveh, also known in early modern times as Kouyunjik, was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern bank of the Tigris River and was the capital and largest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, as well as the largest city in the world for several decades. Today, it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and the country's Nineveh Governorate takes its name from it.

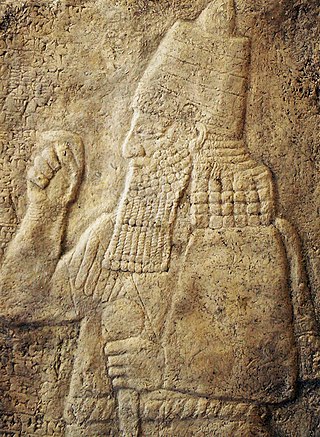

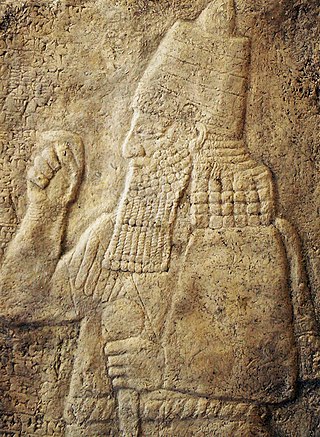

Sennacherib was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC to his own death in 681 BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous Assyrian kings for the role he plays in the Hebrew Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant. Other events of his reign include his destruction of the city of Babylon in 689 BC and his renovation and expansion of the last great Assyrian capital, Nineveh.

The 7th century BC began the first day of 700 BC and ended the last day of 601 BC.

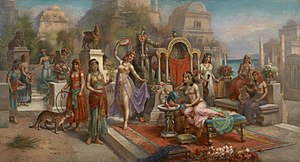

Nebuchadnezzar II, also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second Neo-Babylonian emperor, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Historically known as Nebuchadnezzar the Great, he is typically regarded as the empire's greatest king. Nebuchadnezzar remains famous for his military campaigns in the Levant, for his construction projects in his capital, Babylon, including the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and for the role he plays in Jewish history. Ruling for 43 years, Nebuchadnezzar was the longest-reigning king of the Babylonian dynasty. By the time of his death, he was among the most powerful rulers in the world.

Sippar was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its tell is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, some 69 km (43 mi) north of Babylon and 30 km (19 mi) southwest of Baghdad. The city's ancient name, Sippar, could also refer to its sister city, Sippar-Amnanum ; a more specific designation for the city here referred to as Sippar was Sippar-Yahrurum.

Nabopolassar was the founder and first king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from his coronation as king of Babylon in 626 BC to his death in 605 BC. Though initially only aimed at restoring and securing the independence of Babylonia, Nabopolassar's uprising against the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which had ruled Babylonia for more than a century, eventually led to the complete destruction of the Assyrian Empire and the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in its place.

Berossus or Berosus was a Hellenistic-era Babylonian writer, a priest of Bel Marduk and astronomer who wrote in the Koine Greek language, and who was active at the beginning of the 3rd century BC. Versions of two excerpts of his writings survive, at several removes from the original.

Robert Johann Koldewey was a German archaeologist, famous for his in-depth excavation of the ancient city of Babylon in modern-day Iraq. He was born in Blankenburg am Harz in Germany, the duchy of Brunswick, and died in Berlin at the age of 69.

Shammuramat, also known as Sammuramat or Shamiram and Semiramis, was a powerful queen of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Beginning her career as the primary consort of the king Shamshi-Adad V, Shammuramat reached an unusually prominent position in the reign of her son Adad-nirari III. Though there is dispute in regard to Shammuramat's formal status and position, and if she should be considered a co-regent, it is clear that she was among the most powerful and influential women of the ancient Near East; she is the only known Assyrian queen to have retained her status as queen after the death of her husband and the only known ancient Assyrian woman to have partaken in, and perhaps even led, a military campaign.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and being firmly established through the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire was conquered by the Achaemenid Persian Empire in 539 BC, marking the collapse of the Chaldean dynasty less than a century after its founding.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East throughout much of the 8th and 7th centuries BC, becoming the largest empire in history up to that point. Because of its geopolitical dominance and ideology based in world domination, the Neo-Assyrian Empire is by many researchers regarded to have been the first world empire in history. It influenced other empires of the ancient world culturally, governmentally, and militarily, including the Babylonians, the Achaemenids, and the Seleucids. At its height, the empire was the strongest military power in the world and ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as parts of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia.

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, also known as the Seven Wonders of the World or simply the Seven Wonders, is a list of seven notable structures present during classical antiquity. The first known list of seven wonders dates back to the 2nd–1st century BC.

Babylon was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Iraq. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-speaking region of Babylonia, with its rulers establishing two important empires in antiquity, namely the 19th–16th century BC Old Babylonian Empire and the 7th–6th century BC Neo-Babylonian Empire, and the city would also be used as a regional capital of other empires, such as the Achaemenid Empire. Babylon was one of the most important urban centres of the ancient Near East until its decline during the Hellenistic period.

This is a history of notable hydroculture phenomena. Ancient hydroculture proposed sites and modern revolutionary works are mentioned. Included in this history are all forms of aquatic and semi-aquatic based horticulture that focus on flora: aquatic gardening, semi-aquatic crop farming, hydroponics, aquaponics, passive hydroponics, and modern aeroponics.

Naqiʾa or Naqia (Akkadian: Naqīʾa, also known as Zakūtu, was a wife of the Assyrian king Sennacherib and the mother of his son and successor Esarhaddon. Naqiʾa is the best documented woman in the history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and she reached an unprecedented level of prominence and public visibility; she was perhaps the most influential woman in Assyrian history. She is one of the few ancient Assyrian women to be depicted in artwork, to commission her own building projects, and to be granted laudatory epithets in letters by courtiers. She is also the only known ancient Assyrian figure other than kings to write and issue a treaty.

Jerwan is a locality north of Mosul in the Nineveh Province of Iraq. The site is clear of vegetation and is sparsely settled.

Stephanie Mary Dalley FSA is a British Assyriologist and scholar of the Ancient Near East. Prior to her retirement, she was a teaching Fellow at the Oriental Institute, Oxford. She is known for her publications of cuneiform texts and her investigation into the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and her proposal that it was situated in Nineveh, and constructed during Sennacherib's rule.

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ultimately fall during their rule, the Sargonid dynasty ruled the country during the apex of its power and Sargon II's three immediate successors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian monarchs. Though the dynasty encompasses seven Assyrian kings, two vassal kings in Babylonia and numerous princes and princesses, the term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.

The Statue of Marduk, also known as the Statue of Bêl, was the physical representation of the god Marduk, the patron deity of the ancient city of Babylon, traditionally housed in the city's main temple, the Esagila. There were seven statues of Marduk in Babylon, but 'the' Statue of Marduk generally refers to the god's main statue, placed prominently in the Esagila and used in the city's rituals. This statue was nicknamed the Asullḫi and was made of a type of wood called mēsu and covered with gold and silver.