Kalhana was the author of Rajatarangini, an account of the history of Kashmir. He wrote the work in Sanskrit between 1148 and 1149. All information regarding his life has to be deduced from his own writing, a major scholar of which is Mark Aurel Stein.

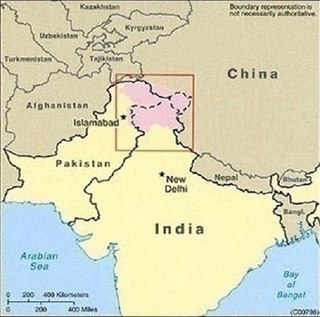

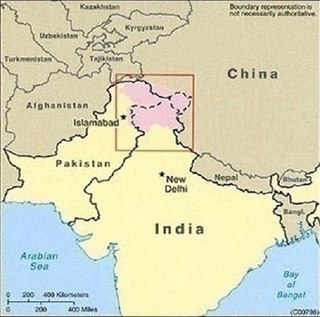

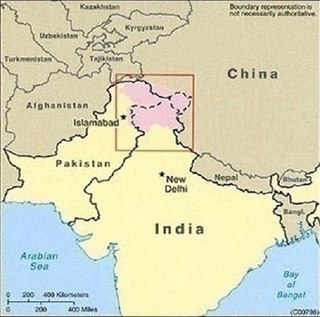

Lalitaditya alias Muktapida was a monarch belonging to the Karkota dynasty of Kashmir region in the Indian subcontinent. The Tang dynasty chronicles present him as a vassal-ally of the Tangs.

Zamindawar is a historical region of Afghanistan. It is a very large and fertile valley the main sources for irrigation is the Helmand River. Zamindawar is located in the greater territory of northern Helmand and encompasses the approximate area of modern-day Baghran, Musa Qala, Naw Zad, Kajaki and Sangin districts. It was a district of hills, and of wide, well populated, and fertile valleys watered by important tributaries of the Helmand. The principal town was Musa Qala, which stands on the banks of a river of the same name, about 60 km north of the city of Grishk.

Shingara, better known as Sultan Sikandar Shah Miri, also by his sobriquet Sikandar Butshikan was the seventh Sultan of Kashmir and a member of Shah Mir dynasty who ruled from 1389 until his death in 1413.

Buddhism was an important part of the classical Kashmiri culture, as is reflected in the Nilamata Purana and Kalhana's Rajatarangini. Buddhism is generally believed to have become dominant in Kashmir in the time of Emperor Ashoka, although it was widespread there long before his time, enjoying the patronage not only of Buddhist rulers but of Hindu rulers too. From Kashmir, it spread to the neighbouring Ladakh, Tibet and China proper. Accounts of patronage of Buddhism by the rulers of Kashmir are found in the Rajatarangini and also in the accounts of three Chinese visitors to Kashmir during 630-760 AD.

The Shah Mir dynasty was a dynasty that ruled the Kashmir Sultanate in the Indian subcontinent. The dynasty is named after its founder, Shah Mir.

Sultan Shamsu'd-Din Shah Mir or simply Shamsu'd-Din Shah or Shah Mir was the second Sultan of Kashmir and founder of the Shah Mir dynasty. Shah Mir is believed to have come to Kashmir during the rule of Suhadeva, where he rose to prominence. After the death of Suhadeva and his brother, Udayanadeva, Shah Mir proposed marriage to the reigning queen, Kota Rani. She refused and continued her rule for five months till 1339, appointing Bhutta Bhikshana as prime minister. After the death of Kota Rani, Shah Mir established his own kingship, founding the Shah Mir dynasty in 1339, which lasted till 1561.

Jat Muslim or Musalman Jat, also spelled Jatt or Jutt, are an elastic and diverse ethno-social subgroup of the Jat people, who are composed of followers of Islam and are native to the northern regions of the Indian subcontinent. They are found primarily throughout the Sindh and Punjab regions of Pakistan. Jats began converting to Islam from the early Middle Ages onward and constitute a distinct subgroup within the diverse community of Jat people.

The Lohara dynasty was a Kashmiri Hindu dynasty that ruled over Kashmir and surrounding regions in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, for more than 3 centuries between 1003 CE and approximately 1320 CE. The early history of the dynasty was described in the Rajatarangini, a work written by Kalhana in the mid-12th century and upon which many and perhaps all studies of the first 150 years of the dynasty depend. Subsequent accounts, which provide information up to and beyond the end of the dynasty come from Jonarāja and Śrīvara. The later rulers of the dynasty were weak: internecine fighting and corruption were endemic during this period, with only brief years of respite, making the dynasty vulnerable to the growth of Islamic conquests in the region.

The Martand Sun Temple is a Hindu temple located near the city of Anantnag in the Kashmir Valley of Jammu and Kashmir, India. It dates back to the eighth century CE and was dedicated to Surya, the chief solar deity in Hinduism; Surya is also known by the Sanskrit-language synonym Martand. The temple was destroyed by Sikandar Shah Miri.

Meghavahana was ruler and founder of second Gonanda dynasty of Kashmir during middle of first millennium CE. Meghavahana was 80th ruler of the Gonanda line of rulers, he was followed by 81st ruler Pravarasena.

Parihaspora or Parihaspur or Paraspore or Paraspur was a small town 22 kilometres (14 mi) northwest of Srinagar in the Kashmir Valley. It was built on a plateau above the Jhelum River. It was built by Lalitaditya Muktapida and served as the capital of Kashmir during his reign.

Dharmasvamin was a Tibetan monk and pilgrim who travelled to India between 1234 and 1236. His biography by Upasaka Chos-dar provides an eyewitness account of the times.

The Karkota dynasty ruled over the Kashmir valley and some northern parts of the Indian subcontinent during 7th and 8th centuries. Their rule saw a period of political expansion, economic prosperity and emergence of Kashmir as a centre of culture and scholarship.

Jalauka was, according to the 12th century Kashmiri chronicle, the Rajatarangini, a king of Kashmir, who cleared the valley of oppressing Malechas. Jaluka was reputed to have been an active and vigorous king of Kashmir, who expelled certain intrusive foreigners, and conquered the plains as far as Kannauj. Jalauka was devoted to the worship of the Hindu god Shiva and the Divine Mothers, in whose honour he and his queen, Isana-devi, erected many temples in places which can be identified.Ashoka’s death his mighty empire had fragmented into as many as four or five regional kingdoms each ruled by his sons or grandsons, among them Jalauka in Kashmir, who reversed his father’s policies in favour of Shaivism and led a successful campaign against the Graeco-Bactrians, themselves seeking to take advantage of the power vacuum in north-west India to reclaim Taxila.

The Utpala dynasty was a medieval kingdom which ruled over the Kashmir region in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent from the 9th to 10th century CE. The kingdom was established by Avantivarman, ending the rule of the Karkota dynasty in 855 CE. The cities of Avantipur and Suyapur were founded during the reign, and many Hindu temples dedicated to both Vishnu and Shiva and Buddhist monasteries were built, notable of which is the Avantiswara and Avantiswami temples.

The Battle of Kasahrada, also known as Battle of Kayadara or Battle of Gadararaghatta was fought in 1178 at modern Kasahrada in Sirohi district near Mount Abu in present-day Rajasthan. It was fought between the Rajput Confederacy led by Mularaja II and the invading Ghurid forces led by Muhammad of Ghor, during which the Ghurid forces were signally defeated.

The Second Gonanda dynasty, was a Kashmiri Hindu dynasty. According to Kalhana, this dynasty ruled Kashmir just before the Karkotas.

King Ashoka, of the Gonandiya dynasty, was a king of the region of Kashmir according to Kalhana, the 12th century CE historian who wrote the Rajatarangini.

Zhun also known as Zhuna, Zhūn or Zūn is a Solar deity, the chief god of Zunbils and the Hephthalite god of the sun. He served as a dispenser of evil and a bringer of justice and oaths, he was a divine judge and a great warrior of the people who held truthfulness in the highest honur. He may have also been the creator and lord of the universe, though this particular belief is unfounded, he was also a lord of mountains in a mountainous place and a lord of the river Oxus, which may have held the primeval waters. He is represented with flames radiating from his head on coins. Statues were adorned with gold and used rubies for eyes. Huen Tsang calls him "Sungir".