Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area in Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States. Unlike most other leading medical schools, HMS does not operate in conjunction with a single hospital but is directly affiliated with several teaching hospitals in the Boston area. Affiliated teaching hospitals and research institutes include Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Children's Hospital, McLean Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, The Baker Center for Children and Families, and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital.

The Warren Anatomical Museum, housed within Harvard Medical School's Countway Library of Medicine, was founded in 1847 by Harvard professor John Collins Warren, whose personal collection of 160 unusual and instructive anatomical and pathological specimens now forms the nucleus of the museum's 15,000-item collection. The Warren also has objects significant to medical history, such as the inhaler used during the first public demonstration of ether-assisted surgery in 1846, and the skull of Phineas Gage, who survived a large iron bar being driven through his brain. The museum's first curator was J.B.S. Jackson.

Joseph Edward Murray was an American plastic surgeon who performed the first successful human kidney transplant on identical twins Richard and Ronald Herrick on December 23, 1954.

Oral and maxillofacial surgery is a surgical specialty focusing on reconstructive surgery of the face, facial trauma surgery, the oral cavity, head and neck, mouth, and jaws, as well as facial cosmetic surgery/facial plastic surgery including cleft lip and cleft palate surgery.

The Mütter Museum is a medical history and science museum located in the Center City area of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It contains a collection of anatomical and pathological specimens, wax models, and antique medical equipment. The museum is part of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The original purpose of the collection, donated by Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter on December 11th 1858, was for the education of both medical professionals and the public. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia is itself not a teaching organization, but rather a "scientific body dedicated to the advancement of science and medicine".

The Harvard School of Dental Medicine (HSDM) is the dental school of Harvard University. It is located in the Longwood Medical Area in Boston, Massachusetts. In addition to the DMD degree, HSDM offers specialty training programs, advanced training programs, and a PhD program through the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. The program considers dentistry a specialty of medicine. Therefore, all students at HSDM experience dual citizenship between Harvard School of Dental Medicine and Harvard Medical School. Today, HSDM is the smallest school at Harvard University with a total student body of 280.

Harvard Library is the network of Harvard University's libraries and services. It is the oldest library system in the United States and both the largest academic library and largest private library in the world. Its collection holds over 20 million volumes, 400 million manuscripts, 10 million photographs, and one million maps.

Tufts University School of Dental Medicine (TUSDM) is a private, American dental school located in the Chinatown neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, and is connected to Tufts Medical Center. It is one of the 8 graduate schools that comprise Tufts University. Founded in 1868 as Boston Dental College by Dr. Isaac J. Wetherbee, the university is the second oldest dental school in the city, and one of the oldest in the country.

Jeffries Wyman was an American naturalist and anatomist, born in Chelmsford, Massachusetts. Wyman died in Bethlehem, New Hampshire of a pulmonary hemorrhage.

John White Webster was an American professor of chemistry and geology at Harvard Medical College. In 1850, he was convicted of murder in the Parkman–Webster murder case and hanged.

Myrtelle May Moore Canavan was an American physician and medical researcher. She was one of the first female pathologists and is best known for publishing a description of Canavan disease in 1931.

Mary Ellen Beck Wohl was Chief of the Division of Respiratory Diseases at Children's Hospital Boston, and served as Associate Director of the General Clinical Research Center until 2002. Since the 1962, when she first joined the staff at Children's Hospital, Wohl specialized in the respiratory diseases of children. She was also a leader in the field of clinical research on cystic fibrosis. She developed a number of techniques to evaluate the function of the lungs in young children and is the author of many research papers in this field.

The Boston Medical Library of Boston, Massachusetts, was originally organized to alleviate the problem that had emerged due to the scattered distribution of medical texts throughout the city. It has evolved into the "largest academic medical library in the world".

The Boston Phrenological Society was formed in 1832 upon the death of a prominent continental phrenologist, Johann Gaspar Spurzheim. Spurzheim was an anatomist and a former pupil of Franz Josef Gall. Spurzheim's brief tour and death popularized phrenology in the United States outside of its controversial place in medical lecture halls, and into the sphere of social reformers and ministers. The Society's formation launched the phrenology movement in the United States. The Boston Phrenological Society was founded by phrenology adherent Nahum Capen on the day of Spurzheim's funeral, November 17, 1832.

The Boston Society for Medical Improvement was an elite society of Boston physicians, established in 1828 for "the cultivation of confidence and good feeling between members of the profession; the eliciting and imparting of information upon the different branches of medical science; and the establishment of a Museum and Library of Pathological Anatomy". It held regular meetings until at least 1917.

Charles Eliot Ware was a prominent Boston physician. He was the husband of Elizabeth Cabot Lee and the father of Mary Lee Ware. These women commissioned the famous Glass Flowers exhibit at the Harvard Museum of Natural History in his memory. Ware was also a close friend of John Holmes, the younger brother of Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

The Gordon Museum of Pathology is a medical museum that is part of King's College London in London, England. It is one of the largest pathology museums in the world and is the largest medical museum in the United Kingdom. Its primary function is to train medical, dental, biomedical and healthcare students and professionals to diagnose diseases.

Robert H. Ivy (1881–1974) was an American oral and plastic surgeon who is known to develop the team approach or multidisciplinary treatment involving care of children with Cleft lip and cleft palate. He is one of the early pioneers in the specialty of plastic surgery due to his surgical experience in World War I. During an intermaxillary fixation technique, Ivy Loop or Eyelet Wiringis named after Dr. Ivy.

Kurt H. Thoma was an American Oral Surgeon known as the founder of the American Board of Oral Pathology. He was also the Editor-in-chief for the Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, and Oral Radiology Journal for 22 years. To many Kurt was recognized as the Father of Oral and maxillofacial pathology and the defender of Oral and maxillofacial surgery and a great teacher of Oral medicine.

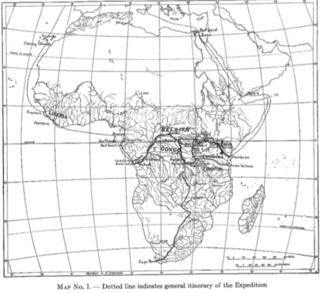

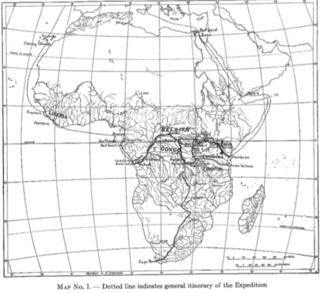

The Harvard Medical African Expedition of 1926–1927 was an eight-man venture sent by Harvard University for the primary purpose of conducting a medical and biological survey of Liberia; the secondary purpose being to then cross Africa from coast to coast - west to east - through the Belgian Congo so as to make a comparative study of their Liberian findings. Furthermore, the Liberian interior was next of kin to being terra incognita in the West, there having been no previous medical or scientific survey of the region, nor any recorded expedition into the Liberian hinterlands. The Expedition leader was Richard Pearson Strong, with the others being zoologists Harold Jefferson Coolidge Jr. and Dr. Glover Morrill Allen, entomologist Dr. Joseph Charles Bequaert, botanist and Washington University in St. Louis Professor David H. Linder, bacteriologist Dr. George C. Shattuck, bacteriologist Dr. Max Theiler, and Assistant Ornithologist Loring Whitman. The Expedition was a success and, while its "chief objective was the investigation of tropical diseases, many zoological specimens were collected and the customs of the native tribes were studied." The story of their travels back and forth across Liberia, and reports of the diseases found that ailed the inhabitants, animals and plants was published in the two-volume The African Republic of Liberia and the Belgian Congo: Based on the Observations Made and Material Collected during the Harvard African Expedition, 1926-1927 written by Dr. Strong in a partnership with other Expedition members and Harvard officials.