Hesperocyparis macrocarpa also known as Cupressus macrocarpa, or the Monterey cypress is a coniferous tree, and is one of several species of cypress trees endemic to California.

Callitropsis nootkatensis, formerly known as Cupressus nootkatensis, is a species of tree in the cypress family native to the coastal regions of northwestern North America. This species goes by many common names including: Nootka cypress, yellow cypress, Alaska cypress, Nootka cedar, yellow cedar, Alaska cedar, and Alaska yellow cedar. The specific epithet nootkatensis is derived from its discovery by Europeans on the lands of a First Nation of Canada, the Nuu-chah-nulth people of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, who were formerly referred to as the Nootka.

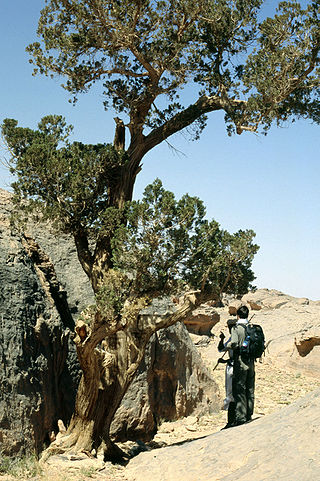

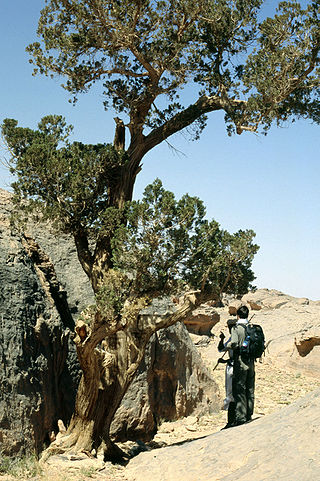

Cupressus dupreziana, the Saharan cypress, or tarout, is a very rare coniferous tree native to the Tassili n'Ajjer mountains in the central Sahara desert, southeast Algeria, where it forms a unique population of trees hundreds of kilometres from any other trees. There are only 233 specimens of this endangered species, the largest about 22 m tall. The majority are estimated to be over 2000 years old, with very little regeneration due to the increasing desertification of the Sahara. Rainfall totals in the area are estimated to be about 30 mm annually. The largest one is named Tin-Balalan is believed to be the oldest tarout tree with a circumference of 12 meters or 36 feet.

Hesperocyparis arizonica, the Arizona cypress, is a North American species of tree in the cypress family Cupressaceae, native to the southwestern United States and Mexico. Populations may be scattered rather than in large, dense stands.

Hesperocyparis bakeri, previously known Cupressus bakeri, with the common names Baker cypress, Modoc cypress, or Siskiyou cypress, is a rare species of western cypress tree endemic to a small area across far northern California and extreme southwestern Oregon, in the western United States.

Hesperocyparis goveniana commonly known as Californian cypress and Gowen cypress, is a species of western cypress that is endemic to a small area of coastal California near Monterey. It was formerly classified as Cupressus goveniana.

Hesperocyparis guadalupensis, commonly known as Guadalupe cypress, is a species of western cypress from Guadalupe Island in the Pacific Ocean off the western coast of Mexico's Baja Peninsula. It was previously known as Cupressus guadalupensis until 2009. It is a medium sized tree with fine green to blue-green foliage. In its native habitat it depends on water from the fogs that envelop the high northern half of the island. It became an endangered species due to feral goats living on Guadalupe Island that prevented new trees from growing for more than a century. In 2005 the goats were finally removed from its island home as part of an island restoration project. New trees are growing and other plants are beginning to recover though the future of the species is not yet assured. Guadalupe cypress is closely related to the vulnerable Tecate cypress which grows on the mainland in Baja California and southern California. It is used as an ornamental tree in Mediterranean climates, particularly in Europe, but has no significant human uses.

Hesperocyparis lusitanica, the Mexican cypress or cedar-of-Goa, is a species of cypress native to Mexico and Central America. It has also been introduced to Belize, Costa Rica and Nicaragua, growing at 1,200–3,000 metres (3,900–9,800 ft) altitude.

Hesperocyparis macnabiana is a species of western cypress in from California that was previously named Cupressus macnabiana.

Hesperocyparis sargentii is a species of conifer in the family Cupressaceae known by the common name Sargent's cypress. It is endemic to California, where it is known from Mendocino County southwards to Santa Barbara County. This taxon is limited to the Coast Range mountains. It grows in forests with other conifers, as well as chaparral and other local mountain habitat, usually in pure stands on serpentine soils. It generally grows 10 to 15 meters tall, but it is known to exceed 22 meters. On Carson Ridge in Marin County, as well as Hood Mountain in Sonoma County, the species comprises a pygmy forest of trees which do not attain heights greater than 240–360 cm due to high mineral concentrations in the serpentine soil.

The Zayante band-winged grasshopper is a species of insect in the family Acrididae. It is endemic to a small portion of the Santa Cruz Mountains in California.

Hesperocyparis forbesii, with the common names Tecate cypress or Forbes' cypress, is a nonflowering, seed bearing tree species of western cypress native to southwestern North America in California and Baja California. It was formerly known as Cupressus forbesii.

Arctostaphylos confertiflora is a rare species of manzanita known by the common name Santa Rosa Island manzanita. This shrub is endemic to California, where it grows on the sandstone bluffs of Santa Rosa Island in the Channel Islands. This manzanita is listed as an endangered species by the United States Government.

The Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve is a nature preserve of 552 acres (2.23 km2) in the Santa Cruz Mountains of California, United States. The reserve protects several rare and endangered plant and animal species within an area known as the Santa Cruz Sandhills, an ancient seabed containing fossilized marine animals.

The California interior chaparral and woodlands ecoregion covers 24,900 square miles (64,000 km2) in an elliptical ring around the California Central Valley. It occurs on hills and mountains ranging from 300 feet (91 m) to 3,000 feet (910 m). It is part of the Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub biome, with cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers. Temperatures within the coast can range from 53° to 65 °F and 32° to 60 °F within the mountains. Many plant and animal species in this ecoregion are adapted to periodic fire.

Hesperocyparis stephensonii is a species of western cypress known as the Cuyamaca cypress that is found only in two very small areas in Southern California and northwestern Baja California.

Hesperocyparis nevadensis is a species of western cypress tree with the common name Paiute cypress native to a small area in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California in the western United States. It was formerly known as Cupressus nevadensis.

Hesperocyparis is a genus of trees in the family Cupressaceae, containing North American species otherwise assigned to the genus Cupressus. They are found throughout western North America. Only a few species have wide ranges, with most being restricted-range endemics.

Hesperocyparis montana, commonly known as the San Pedro Mártir cypress or San Pedro cypress, is a species of conifer. It is a tree native to the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir of Baja California state in northwestern Mexico.

Neoendemism is one of two sub-categories of endemism, the ecological state of a species being unique to a defined geographic location. Specifically, neoendemic species are those that have recently arisen, through divergence and reproductive isolation or through hybridization and polyploidy in plants. Paleoendemism, the other sub-category, refers to species that were formerly widespread but are now restricted to a smaller area.