Related Research Articles

Lilith, also spelt Lilit, Lilitu, or Lilis, is a female figure in Mesopotamian and Judaic mythology, theorized to be the first wife of Adam and supposedly the primordial she-demon. Lilith is cited as having been "banished" from the Garden of Eden for not complying with and obeying Adam. She is thought to be mentioned in Biblical Hebrew in the Book of Isaiah, and in Late Antiquity in Mandaean mythology and Jewish mythology sources from 500 CE onward. Lilith appears in historiolas in various concepts and localities that give partial descriptions of her. She is mentioned in the Babylonian Talmud, in the Book of Adam and Eve as Adam's first wife, and in the Zohar Leviticus 19a as "a hot fiery female who first cohabited with man". Many traditional rabbinic authorities, including Maimonides and Menachem Meiri, reject the existence of Lilith.

Magic, sometimes spelled magick, is an ancient practice rooted in rituals, spiritual divinations, and/or cultural lineage—with an intention to invoke, manipulate, or otherwise manifest supernatural forces, beings, or entities in the natural world. It is a categorical yet often ambiguous term which has been used to refer to a wide variety of beliefs and practices, frequently considered separate from both religion and science.

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology Asaruludu is one of the Anunnaki. His name is also spelled Namshub, Asarludu, and Asarluhi (𒀭𒍂𒇽𒄭). The etymology and meaning of his name are unclear.

Mandaic is a southeastern Aramaic variety in use by the Mandaean community, traditionally based in southern parts of Iraq and southwest Iran, for their religious books. Classical Mandaic is still employed by Mandaean priests in liturgical rites. The modern descendant of Classical Mandaic, known as Neo-Mandaic or Modern Mandaic, is spoken by a small section of Mandaeans around Ahvaz and Khorramshahr in the southern Iranian Khuzestan province.

An incantation, a spell, a charm, an enchantment or a bewitchery, is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremonial rituals or prayers. In the world of magic, wizards, witches, and fairies allegedly perform incantations.

Mandaeism, sometimes also known as Nasoraeanism or Sabianism, is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion. Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Mandaeans consider Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem and John the Baptist prophets, with Adam being the founder of the religion and John being the greatest and final prophet.

The Greek Magical Papyri is the name given by scholars to a body of papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt, written mostly in ancient Greek, which each contain a number of magical spells, formulae, hymns, and rituals. The materials in the papyri date from the 100s BCE to the 400s CE. The manuscripts came to light through the antiquities trade, from the 1700s onward. One of the best known of these texts is the Mithras Liturgy.

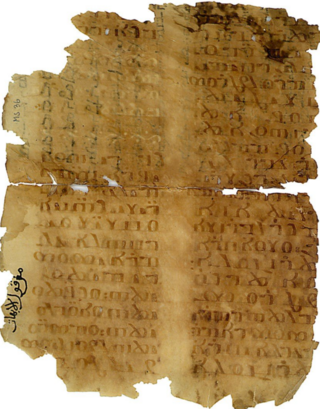

Christian Palestinian Aramaic (CPA) was a Western Aramaic dialect used by the Melkite Christian community in Palestine and Transjordan between the fifth and thirteenth centuries. It is preserved in inscriptions, manuscripts and amulets. All the medieval Western Aramaic dialects are defined by religious community. CPA is closely related to its counterparts, Jewish Palestinian Aramaic (JPA) and Samaritan Aramaic (SA). CPA shows a specific vocabulary that is often not paralleled in the adjacent Western Aramaic dialects.

Agnes Smith Lewis (1843–1926) and Margaret Dunlop Gibson (1843–1920), nées Smith, were English Semitic scholars and travellers. As the twin daughters of John Smith of Irvine, Ayrshire, Scotland, they learned more than 12 languages between them, specialising in Arabic, Christian Palestinian Aramaic, and Syriac, and became acclaimed scholars in their academic fields, and benefactors to the Presbyterian Church of England, especially to Westminster College, Cambridge.

An incantation bowl, also known as a demon bowl, devil-trap bowl, or magic bowl, is a form of early protective magic found in what is now Iraq and Iran. Produced in the Middle East during late antiquity from the sixth to eighth centuries, particularly in Upper Mesopotamia and Syria, the bowls were usually inscribed in a spiral, beginning from the rim and moving toward the center. Most are inscribed in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.

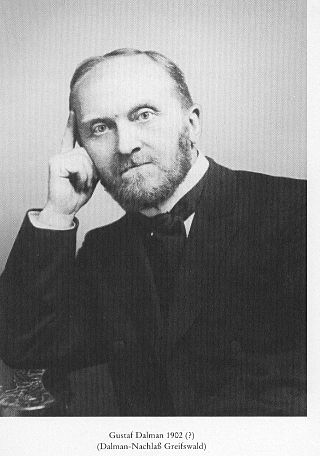

Gustaf Hermann Dalman was a German Lutheran theologian and orientalist. He did extensive field work in Palestine before the First World War, collecting inscriptions, poetry, and proverbs. He also collected physical articles illustrative of the life of the indigenous farmers and herders of the country, including rock and plant samples, house and farm tools, small archaeological finds, and ceramics. He pioneered the study of biblical and early post-biblical Aramaic, publishing an authoritative grammar (1894) and dictionary (1901), as well as other works. His collection of 15,000 historic photographs and 5,000 books, including rare 16th century prints, and maps formed the basis of the Gustaf Dalman Institute at the Ernst Moritz Arndt University, Greifswald, which commemorates and continues his work.

The "Mithras Liturgy" is a text from the Great Magical Papyrus of Paris, part of the Greek Magical Papyri, numbered PGM IV.475-834. The modern name by which the text is known originated in 1903 with Albrecht Dieterich, its first translator, based on the invocation of Helios Mithras as the god who will provide the initiate with a revelation of immortality. The text is generally considered a product of the religious syncretism characteristic of the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial era, as were the Mithraic mysteries themselves. Some scholars have argued that it has no direct connection to particular Mithraic ritual. Others consider it an authentic reflection of Mithraic liturgy, or view it as Mithraic material reworked for the syncretic tradition of magic and esotericism.

Jewish magical papyri are a subclass of papyri with specific Jewish magical uses, and which shed light on popular belief during the late Second Temple Period and after in Late Antiquity. A related category of contemporary evidence are Jewish magical inscriptions, typically on amulets, ostraca, and incantation bowls.

4Q510–511, also given the title Songs of the Sage or Songs of the Maskil, is a fragmentary Hebrew-language manuscript of a Jewish magical text of incantation and exorcism in the Dead Sea Scrolls, specifically for protection against a list of demons. It is notable for containing the first clear usage of the Hebrew term lilith in relation to a supernatural creature. It is comparable to Aramaic incantation 4Q560 and also 11Q11.

Mullissu is a goddess who is the consort of the Assyrian god Asshur. Mullissu may be identical with the Sumerian goddess Ninlil, wife of the god Enlil, which would parallel the fact that Asshur himself was modeled on Enlil. Mullissu's name was written dnin.líl. Mullissu is identified with Ishtar of Nineveh in the Neo-Assyrian Empire times.

Christa Agnes Tuczay is an Austrian University professor in Medieval German Language and Literature at the Institute of German Studies at the University of Vienna. Tuczay is well known for her research on narratives and fairytales in the Middle Ages.

Theodore Kwasman is an American Assyriologist and professor for Jewish studies. He is best known for his discovery of the first lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Mandaic lead rolls, sometimes also known as Mandaic amulets or sheets, which are related to Palestinian and Syrian metal amulets, are a specific term for a writing medium containing incantations in the Mandaic script incised onto lead sheets with a pin. Some Mandaic incantations are found on gold and silver sheets. They are rolled up and then inserted into a metal capsule with loops on it to be worn around the neck on a string or necklace.

The Aramaic Uruk incantation acquired 1913 by the Louvre, Paris and stored there under AO 6489 is a unique Aramaic text written in Late Babylonian cuneiform syllable signs and dates to the Seleucid Empire ca. 150 BCE. The finding site is the reš-sanctuary in the ancient city of Uruk (Warka), therefore the label “Uruk”. Particular about this incantation text is that it contains a magical historiola which is divided up into two nearly repetitive successive parts, a text genre that finds its continuation in the Aramaic magical text corpus of late antiquity from Iraq and Iran, most prominently in incantation bowls and Mandaic lead rolls.

References

- 1 2 Fritz Graf, "Historiola", in Brill’s New Pauly . Consulted online on 29 December 2020.

- ↑ Faraone, Christopher (1988). "Hermes but No Marrow: Another Look at a Puzzling Magical Spell". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 72: 279–286. JSTOR 20186827.

- ↑ Ceravolo, Marinella (2022). L'historiola nella Mesopotamia antica. Mito, rito e performatività. Rome: Bulzoni. ISBN 978-88-6897-284-4.

- ↑ Frankfurter, David (1995). "Narrating Power: The Theory and Practice of the Magical Historiola in Ritual Spells". In Meyer, Marvin; Mirecki, Paul (eds.). Ancient Magic and Ritual Power. E. J. Brill. ISBN 0-8014-2550-6.

- ↑ Müller-Kessler, Christa (1996). "The Story of Bguzan-Lilit, Daughter of Zanay-Lilit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 116 (2): 185–195. doi:10.2307/605694. JSTOR 605694.

- ↑ Müller-Kessler, Christa (1999). "Aramäische Beschwörungen und astronomische Omina in nachbabylonischer Zeit: Das Fortleben mesopotamischer Kultur im Vorderen Orient." In Johannes Renger (ed.), Babylon: Focus Mesopotamischer Geschichte, Wiege früher Gelehrsamkeit, Mythos in der Moderne. 2. Internationales Colloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft, Berlin 1998. Saarbrücken: SDV, pp. 432–443. ISBN 3-930843-54-4

- ↑ Müller-Kessler, Christa (2017). "Zauberschalen und ihre Umwelt. Ein Überblick über das Schreibmedium Zauberschale". In Kamran, Jens; Schäfer, Rolf; Witte, Markus (eds.). Zauber und Magie im antiken Palästina und in seiner Umwelt. Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins, 46. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 77–84. ISBN 978-3-447-10781-5

- ↑ Naveh, Joseph; Shaked, Shaul (1985). Amulets and Magic Bowls: Aramaic Incantations of Late Antiquity. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, pp. 111–124. ISBN 965-223-531-8

- ↑ Swartz, Michael D. (1996). Scholastic Magic: Ritual and Revelation in Early Jewish Mysticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 198–199. OCLC 884012615 . Retrieved 14 December 2014.