Ruthenia is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms for Kievan Rus', the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia and, after their collapse, for East Slavic and Eastern Orthodox regions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, corresponding to what is now Ukraine and Belarus.

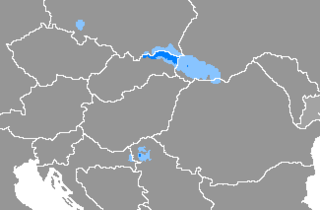

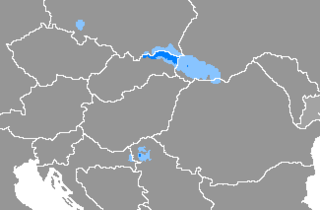

Rusyn, is an East Slavic language spoken by Rusyns in parts of Central and Eastern Europe, and written in the Cyrillic script. Within the community, the language is also referred to by the older folk term, руснацькый язык, rusnac'kyj jazyk, 'Rusnak language', or simply referred to as speaking our way. The majority of speakers live in an area known as Carpathian Rus' that spans from Transcarpathia, westward into eastern Slovakia and south-east Poland. There is also a sizeable Pannonian Rusyn linguistic island in Vojvodina, Serbia, as well as a Rusyn diaspora throughout the world. Per the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, Rusyn is officially recognized as a protected minority language by Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Poland, Serbia, and Slovakia.

Ruthenian and Ruthene are exonyms of Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term Rutheni was used in medieval sources to describe all Eastern Slavs of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as an exonym for people of the former Kievan Rus', thus including ancestors of the modern Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Rusyns. The use of Ruthenian and related exonyms continued through the early modern period, developing several distinctive meanings, both in terms of their regional scopes and additional religious connotations.

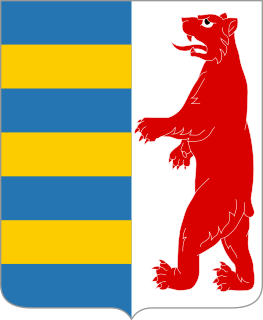

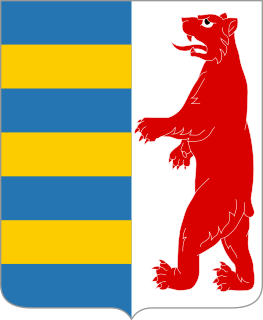

Carpathian Ruthenia is a historical region on the border between Central and Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast, with smaller parts in eastern Slovakia and the Lemko Region in Poland.

Lemkos are an ethnic group inhabiting the Lemko Region of Carpathian Rus', an ethnographic region in the Carpathian Mountains and foothills spanning Ukraine, Slovakia and Poland.

Rusyns, also known as Carpatho-Rusyns, or Rusnaks, are an East Slavic ethnic group from the Eastern Carpathians in Central Europe. They speak Rusyn, an East Slavic language variety, treated variously as either a distinct language or a dialect of the Ukrainian language. As traditional adherents of Eastern Christianity, the majority of Rusyns are Eastern Catholics, though a minority of Rusyns still practice Eastern Orthodoxy. Rusyns primarily self-identify as a distinct Slavic people and they are recognized as such in Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia, and Slovakia, where they have official minority status. Alternatively, some identify more closely with their country of residence, while others are a branch of the Ukrainian people.

The Hutsuls are an ethnic group spanning parts of western Ukraine and Romania. They have often been officially and administratively designated as a subgroup of Ukrainians and are largely regarded as constituting a part of the broader Ukrainian ethnic group.

Canton is a historic waterfront neighborhood in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. The neighborhood is along Baltimore's outer harbor in the southeastern section of the city, roughly two miles east of Baltimore's downtown district and next to or near the neighborhoods of Patterson Park, Fell's Point, Highlandtown, and Brewers Hill.

Rusyn Americans are citizens of the United States of America, with ancestors who were Rusyns, from Carpathian Ruthenia, or neighboring areas of Central Europe. However, some Rusyn Americans, also or instead identify as Ukrainian Americans, Russian Americans, or even Slovak Americans.

Lemko-Rusyn People's Republic, often known also as the Lemko-Rusyn Republic, just the Lemko Republic, or the Florynka Republic was a short-lived state founded on 5 December 1918 in the aftermath of World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was centered on Florynka, a village in the south-east of present-day Poland. Being Russophile, its intent was unification with a democratic Russia and was opposed to a union with the West Ukrainian People's Republic. A union with Russia proved impossible, so the Republic then attempted to join Subcarpathian Rus' as an autonomous province of Czechoslovakia. This, however, was opposed by the then governor of Subcarpathian Rus', Gregory Žatkovich.

The Carpatho-Rusyn Society is a non-profit cultural organization located in the United States dedicated to promoting Carpatho-Rusyn culture and history. It was established in Pittsburgh in 1994 and is the largest exclusively Carpatho-Rusyn organization in North America with over 3,000 members.

East Monument Historic District or Little Bohemia, is a national historic district in Baltimore, Maryland. It is a large residential area with a commercial strip along East Monument Street. It comprises approximately 88 whole and partial blocks. The residential area is composed primarily of rowhomes that were developed, beginning in the 1870s, as housing for Baltimore's growing Bohemian (Czech) immigrant community. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries the neighborhood was the heart of the Bohemian community in Baltimore. The Bohemian National Parish of the Roman Catholic Church, St. Wenceslaus, is located in the neighborhood. The historic district includes all of McElderry Park and Milton-Montford, most of Middle East and Madison-Eastend, and parts of Ellwood Park.

The history of Czechs in Baltimore dates back to the mid-19th century. Thousands of Czechs immigrated to East Baltimore during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming an important component of Baltimore's ethnic and cultural heritage. The Czech community has founded a number of cultural institutions to preserve the city's Czech heritage, including a Roman Catholic church, a heritage association, a gymnastics association, an annual festival, a language school, and a cemetery. During the height of the Czech community in the late 19th century and early 20th century, Baltimore was home to 12,000 to 15,000 people of Czech birth or heritage. The population began to decline during the mid-to-late 20th century, as the community assimilated and aged, while many Czech Americans moved to the suburbs of Baltimore. By the 1980s and early 1990s, the former Czech community in East Baltimore had been almost entirely dispersed, though a few remnants of the city's Czech cultural legacy still remain.

St. Michael the Archangel Ukrainian Catholic Church is a Ukrainian Catholic church of located in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded to initially serve the needs of the Ukrainian immigrant community in Baltimore.

The history of Poles in Baltimore dates back to the late 19th century. The Polish community is largely centered in the neighborhoods of Canton, Fell's Point, Locust Point, and Highlandtown. Poles are the largest Slavic ethnic group in the city and one of the largest European ethnic groups.

There have been a variety of ethnic groups in Baltimore, Maryland and its surrounding area for 12,000 years. Prior to European colonization, various Native American nations have lived in the Baltimore area for nearly 3 millennia, with the earliest known Native inhabitants dating to the 10th millennium BCE. Following Baltimore's foundation as a subdivision of the Province of Maryland by British colonial authorities in 1661, the city became home to numerous European settlers and immigrants and their African slaves. Since the first English settlers arrived, substantial immigration from all over Europe, the presence of a deeply rooted community of free black people that was the largest in the pre-Civil War United States, out-migration of African-Americans from the Deep South, out-migration of White Southerners from Appalachia, out-migration of Native Americans from the Southeast such as the Lumbee and the Cherokee, and new waves of more recent immigrants from Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia and Africa have added layers of complexity to the workforce and culture of Baltimore, as well as the religious and ethnic fabric of the city. Baltimore's culture has been described as "the blending of Southern culture and [African-American] migration, Northern industry, and the influx of European immigrants—first mixing at the port and its neighborhoods...Baltimore’s character, it’s uniqueness, the dialect, all of it, is a kind of amalgamation of these very different things coming together—with a little Appalachia thrown in...It’s all threaded through these neighborhoods", according to the American studies academic Mary Rizzo.

The history of Russians in Baltimore dates back to the mid-19th century. The Russian community is a growing population and constitutes a major source of new immigrants to the city. Historically the Russian community was centered in East Baltimore, but most Russians now live in Northwest Baltimore's Arlington neighborhood and in Baltimore's suburb of Pikesville.

The history of Hispanics and Latinos in Baltimore dates back to the mid-20th century. The Hispanic and Latino community of Baltimore is the fastest growing ethnic group in the city. There is a significant Hispanic/Latino presence in many Southeast Baltimore neighborhoods, particularly Highlandtown, Upper Fell's Point, and Greektown. Overall Baltimore has a small but growing Hispanic population, primarily in the Southeast portion of the area from Fells Point to Dundalk.

The National Slavic Museum in Fell's Point, Baltimore is a museum dedicated to the documentation of the Polish and Slavic heritage of Baltimore, including Baltimore's Belarusian, Bulgarian, Carpatho-Rusyn, Croatian, Czech, Lemko, Moravian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovene, and Ukrainian heritage.

The history of the Irish in Baltimore dates back to the early and mid-19th century. The city's Irish-American community is centered in the neighborhoods of Hampden, Canton, Highlandtown, Fell's Point and Locust Point.