In politics, lobbying, or advocacy, is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies, but also judges of the judiciary. Lobbying, which usually involves direct, face-to-face contact in cooperation with support staff that may not meet directly face-to-face, is done by many types of people, associations and organized groups, including individuals on a personal level in their capacity as voters, constituents, or private citizens; it is also practiced by corporations in the private sector serving their own business interests; by non-profits and non-governmental organizations in the voluntary sector through advocacy groups to fulfil their mission such as requesting humanitarian aid or grantmaking; and by fellow legislators or government officials influencing each other through legislative affairs in the public sector.

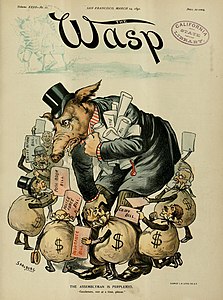

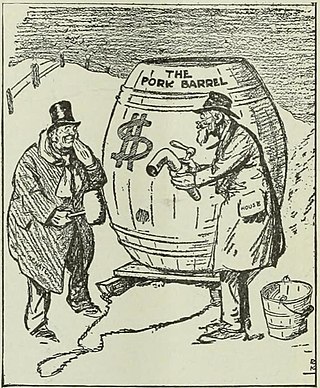

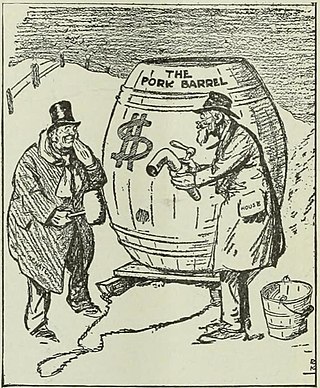

Pork barrel, or simply pork, is a metaphor for the appropriation of government spending for localized projects secured solely or primarily to direct spending to a representative's district.

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee is a lobbying group that advocates pro-Israel policies to the legislative and executive branches of the United States. One of several pro-Israel lobbying organizations in the United States, AIPAC states that it has over 100,000 members, 17 regional offices, and "a vast pool of donors". The organization has been called one of the most powerful lobbying groups in the United States.

Thomas Dale DeLay is an American author and retired politician who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives. A Republican, DeLay represented Texas's 22nd congressional district from 1985 until 2006. He served as House majority leader from 2003 to 2005.

Jack Allan Abramoff is an American lobbyist, businessman, film producer, writer, and convicted felon. He was at the center of an extensive corruption investigation led by Earl Devaney that resulted in his conviction and 21 other people either pleading guilty or being found guilty, including White House officials J. Steven Griles and David Safavian, U.S. Representative Bob Ney, and nine other lobbyists and congressional aides.

The Jack Abramoff Indian lobbying scandal was a United States political scandal exposed in 2005; it related to fraud perpetrated by political lobbyists Jack Abramoff, Ralph E. Reed Jr., Grover Norquist and Michael Scanlon on Native American tribes who were seeking to develop casino gambling on their reservations. The lobbyists charged the tribes an estimated $85 million in fees. Abramoff and Scanlon grossly overbilled their clients, secretly splitting the multi-million dollar profits. In one case, they secretly orchestrated lobbying against their own clients in order to force them to pay for lobbying services.

The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) is a United States law that imposes public disclosure obligations on persons representing foreign interests. It requires "foreign agents"—defined as individuals or entities engaged in domestic lobbying or advocacy for foreign governments, organizations, or persons —to register with the Department of Justice (DOJ) and disclose their relationship, activities, and related financial compensation.

The Sunlight Foundation was an American 501(c)(3) nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that advocated for open government. The organization was founded in April 2006 with the goal of increasing transparency and accountability in the United States Congress, the executive branch, and in state and local governments. The foundation's primary focus was the role of money in politics. The organization sought to increase campaign finance regulations and disclosure requirements. The Sunlight Foundation ceased operations in September 2020.

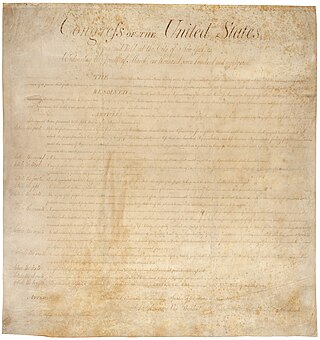

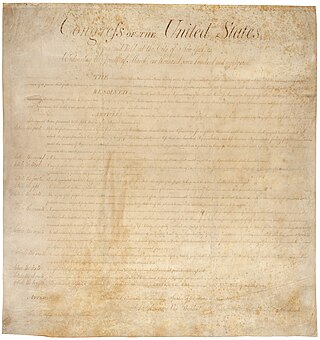

Lobbying in the United States describes paid activity in which special interest groups hire well-connected professional advocates, often lawyers, to argue for specific legislation in decision-making bodies such as the United States Congress. It is often perceived negatively by journalists and the American public; critics consider it to be a form of bribery, influence peddling, and/or extortion. Lobbying is subject to complex rules which, if not followed, can lead to penalties including jail. Lobbying has been interpreted by court rulings as free speech protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Since the 1970s, the numbers of lobbyists and the size of lobbying budgets has grown and become the focus of criticism of American governance.

In the United States, the right to petition is enumerated in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which specifically prohibits Congress from abridging "the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances".

The federal investigations into Jack Abramoff and his political and business dealings are among the broadest and most extensive in American political history, involving well over a dozen offices of the FBI and over 100 FBI agents tasked exclusively to the investigation. Given the extent and complexity of the suspected corruption, an entire inter-governmental task force, involving many federal government departments and agencies, has been established to aid the federal investigation. The U.S. Justice Department has announced that it will not reveal the details of the investigation, or who specifically has been targeted for investigation until indictments are issued. Under his plea agreements, Abramoff is required to answer all questions by federal investigators and prosecutors.

Change Congress was a project aiming to end corruption in the United States Congress by reducing what it considered the distorted influence of money in that legislative body. Founded in 2008 by Lawrence Lessig and Joe Trippi, Change Congress aimed to organize citizens to support political candidates who do not take contributions from PACs and lobbyists, oppose earmarks, support public financing of campaigns, and support more transparency in Congress.

An earmark is a provision inserted into a discretionary spending appropriations bill that directs funds to a specific recipient while circumventing the merit-based or competitive funds allocation process. Earmarks feature in United States Congress spending policy, and they are present in public finance of many other countries as a form of political particularism.

Robert Greeley Kaiser is an American journalist and author. He retired from The Washington Post in early 2014 after a career of more than 50 years on the paper. During his career he served as managing editor (1991–98) and associate editor and senior correspondent (1998-2014). He is the author or co-author of eight books. After retiring he wrote a much-discussed article for the Post explaining his decision to move away from Washington D.C. after living there for most of 70 years.

United States Congress and citizens describes the relation between the public and lawmakers. Essentially, American citizens elect members of Congress every two years who have the duty to represent their interests in the national legislature of the United States. All congressional officials try to serve two distinct purposes which sometimes overlap––representing their constituents and making laws for the nation. There has been debate throughout American history about how to straddle these dual obligations of representing the wishes of citizens while at the same time trying to keep mindful of the needs of the entire nation. Often, compromise is required.

The Saudi Arabia lobby in the United States is a collection of lawyers, public relation firms and professional lobbyists paid directly by the government of Saudi Arabia to lobby the public and government of the United States on behalf of the interests of the government of Saudi Arabia.

Grassroots lobbying is lobbying with the intention of reaching the legislature and making a difference in the decision-making process. Grassroots lobbying is an approach that separates itself from direct lobbying through the act of asking the general public to contact legislators and government officials concerning the issue at hand, as opposed to conveying the message to the legislators directly. Companies, associations and citizens are increasingly partaking in grassroots lobbying as an attempt to influence a change in legislation.

Direct lobbying in the United States are methods used by lobbyists to influence United States legislative bodies. Interest groups from many sectors spend billions of dollars on lobbying.

Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress—and a Plan to Stop It is the sixth book by Harvard law professor and free culture activist Lawrence Lessig. In a departure from the topics of his previous books, Republic, Lost outlines what Lessig considers to be the systemic corrupting influence of special-interest money on American politics, and only mentions copyright and other free culture topics briefly, as examples. He argued that the Congress in 2011 spent the first quarter debating debit-card fees while ignoring what he sees as more pressing issues, including health care reform or global warming or the deficit. Lessig has been described in The New York Times as an "original and dynamic legal scholar."