William Kennedy Laurie Dickson was a British inventor who devised an early motion picture camera under the employment of Thomas Edison.

The following is an overview of the events of 1895 in film, including a list of films released and notable births.

The following is an overview of the events of 1894 in film, including a list of films released and notable births.

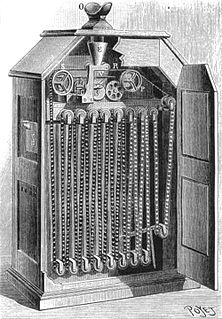

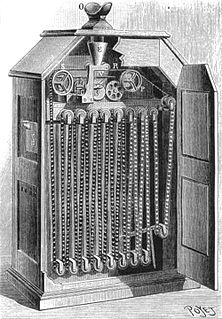

The Kinetoscope is an early motion picture exhibition device, designed for films to be viewed by one person at a time through a peephole viewer window. The Kinetoscope was not a movie projector, but it introduced the basic approach that would become the standard for all cinematic projection before the advent of video. It created the illusion of movement by conveying a strip of perforated film bearing sequential images over a light source with a high-speed shutter. First described in conceptual terms by U.S. inventor Thomas Edison in 1888, it was largely developed by his employee William Kennedy Laurie Dickson between 1889 and 1892. Dickson and his team at the Edison lab in New Jersey also devised the Kinetograph, an innovative motion picture camera with rapid intermittent, or stop-and-go, film movement, to photograph movies for in-house experiments and, eventually, commercial Kinetoscope presentations.

Charles Francis Jenkins was an American engineer who was a pioneer of early cinema and one of the inventors of television, though he used mechanical rather than electronic technologies. His businesses included Charles Jenkins Laboratories and Jenkins Television Corporation. Over 400 patents were issued to Jenkins, many for his inventions related to motion pictures and television.

The zoopraxiscope is an early device for displaying moving images and is considered an important predecessor of the movie projector. It was conceived by photographic pioneer Eadweard Muybridge in 1879. Muybridge used the projector in his public lectures from 1880 to 1895. The projector used 16" glass disks onto which Muybridge had an unidentified artist paint the sequences as silhouettes. This technique eliminated the backgrounds and enabled the creation of fanciful combinations and additional imaginary elements. Only one disk used photographic images, of a horse skeleton posed in different positions. A later series of 12" discs, made in 1892–1894, used outlines drawn by Erwin F. Faber that were printed onto the discs photographically, then colored by hand. These colored discs were probably never used in Muybridge's lectures. All images of the known 71 disks, including those of the photographic disk, were rendered in elongated form to compensate the distortion of the projection. The projector was related to other projecting phenakistiscopes and used some slotted metal shutter discs that were interchangeable for different picture disks or different effects on the screen. The machine was hand-cranked.

The Dickson Experimental Sound Film is a film made by William Dickson in late 1894 or early 1895. It is the first known film with live-recorded sound and appears to be the first motion picture made for the Kinetophone, the proto-sound-film system developed by Dickson and Thomas Edison. The film was produced at the "Black Maria", Edison's New Jersey film studio. There is no evidence that it was ever exhibited in its original format.

Cinematograph or kinematograph is an early term for several types of motion picture film mechanisms. The name was used for movie cameras as well as film projectors, or for complete systems that also provided means to print films.

The Black Maria was Thomas Edison's film production studio in West Orange, New Jersey. It was the world's first film studio.

Major Woodville Latham (1837–1911) was an ordnance officer of the Confederacy during the American Civil War and professor of chemistry at West Virginia University. He was significant in the development of early film technology.

Vitascope was an early film projector first demonstrated in 1895 by Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat. They had made modifications to Jenkins' patented Phantoscope, which cast images via film and electric light onto a wall or screen. The Vitascope is a large electrically-powered projector that uses light to cast images. The images being cast are originally taken by a kinetoscope mechanism onto gelatin film. Using an intermittent mechanism, the film negatives produced up to fifty frames per second. The shutter opens and closes to reveal new images. This device can produce up to 3,000 negatives per minute. With the original Phantoscope and before he partnered with Armat, Jenkins displayed the earliest documented projection of a filmed motion picture in June 1894 in Richmond, Indiana.

The actuality film is a non-fiction film genre that, like the documentary film, uses footage of real events, places, and things. Unlike the documentaries, actuality films are not structured into a larger argument, picture of the phenomenon or coherent whole. In practice, actuality films preceded the emergence of the documentary. During the era of early cinema, actualities—usually lasting no more than a minute or two and usually assembled together into a program by an exhibitor—were just as popular and prominent as their fictional counterparts. The line between "fact" and "fiction" was not as sharply drawn in early cinema as it would become after the documentary came to serve as the predominant non-fiction filmmaking form. An actuality film is not like a newspaper article so much as it is like the still photograph that is published along with the article, with the major difference being that it moves. Apart from the traveling actuality genre, actuality is one film genre that remains strongly related to still photography.

Herman Casler was an American inventor and co-founder of the partnership called the K.M.C.D. Syndicate, along with W.K-L. Dickson, Elias Koopman, and Henry Marvin, which eventually was incorporated into the American Mutoscope Company in December 1895.

The decade of the 1890s in film involved some significant events.

Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph is an 1894 American short black-and-white silent film produced by William K.L. Dickson and starring James J. Corbett. It was only the second boxing match to be filmed following The Leonard-Cushing Fight which had been filmed by Dickson on June 14, 1894.

The phonomotor or "vocal engine" was a device invented by Thomas Edison in 1878 to measure the mechanical force of sound. It converted sound energy or sound power into rotary motion which could drive a machine such as a small saw or drill. It derived from his work on the telephone and phonograph.

Gordon Hendricks (1917–1980) was an American art and film historian.

Antonia Isabella Eugénie Dickson was a writer, lecturer, music composer, and concert pianist. With her brother, William Kennedy Dickson, she authored the History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope, and Kinetophonograph, considered the first book on the history of film, and a biography of Thomas Edison.

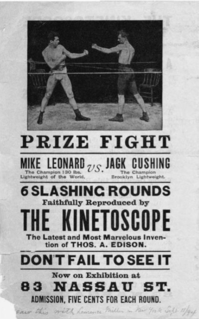

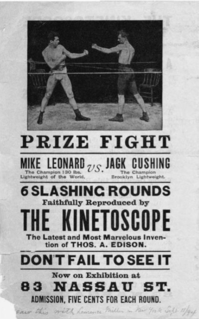

The Leonard-Cushing Fight is an 1894 American short black-and-white silent film produced by William K.L. Dickson, starring Mike Leonard and Jack Cushing. Leonard and Cushing participate in a six round boxing match under special conditions that allow for it to be filmed and displayed on a Kinetograph. Premiered on August 4, 1894 in New York City, the movie is the first sports film ever released. As of 2021, no full print of the film is known to have survived, making it a partially lost film.