A threshing machine or a thresher is a piece of farm equipment that separates grain seed from the stalks and husks. It does so by beating the plant to make the seeds fall out. Before such machines were developed, threshing was done by hand with flails: such hand threshing was very laborious and time-consuming, taking about one-quarter of agricultural labour by the 18th century. Mechanization of this process removed a substantial amount of drudgery from farm labour. The first threshing machine was invented circa 1786 by the Scottish engineer Andrew Meikle, and the subsequent adoption of such machines was one of the earlier examples of the mechanization of agriculture. During the 19th century, threshers and mechanical reapers and reaper-binders gradually became widespread and made grain production much less laborious.

A tractor is an engineering vehicle specifically designed to deliver a high tractive effort at slow speeds, for the purposes of hauling a trailer or machinery such as that used in agriculture, mining or construction. Most commonly, the term is used to describe a farm vehicle that provides the power and traction to mechanize agricultural tasks, especially tillage, and now many more. Agricultural implements may be towed behind or mounted on the tractor, and the tractor may also provide a source of power if the implement is mechanised.

Mechanization is the process of changing from working largely or exclusively by hand or with animals to doing that work with machinery. In an early engineering text, a machine is defined as follows:

Every machine is constructed for the purpose of performing certain mechanical operations, each of which supposes the existence of two other things besides the machine in question, namely, a moving power, and an object subject to the operation, which may be termed the work to be done. Machines, in fact, are interposed between the power and the work, for the purpose of adapting the one to the other.

The modern combine harvester, also called a combine, is a machine designed to harvest a variety of cultivated seeds. Combine harvesters are one of the most economically important labour-saving inventions, significantly reducing the fraction of the population engaged in agriculture. Among the crops harvested with a combine are wheat, rice, oats, rye, barley, corn (maize), sorghum, millet, soybeans, flax (linseed), sunflowers and rapeseed (canola). The separated straw is then either chopped onto the field and ploughed back in, or laid out in rows, ready to be baled and used for bedding and cattle feed.

A traction engine is a steam-powered tractor used to move heavy loads on roads, plough ground or to provide power at a chosen location. The name derives from the Latin tractus, meaning 'drawn', since the prime function of any traction engine is to draw a load behind it. They are sometimes called road locomotives to distinguish them from railway locomotives – that is, steam engines that run on rails.

A treadmill is a device generally used for walking, running, or climbing while staying in the same place. Treadmills were introduced before the development of powered machines to harness the power of animals or humans to do work, often a type of mill operated by a person or animal treading the steps of a treadwheel to grind grain. In later times, treadmills were used as punishment devices for people sentenced to hard labour in prisons. The terms treadmill and treadwheel were used interchangeably for the power and punishment mechanisms.

Threshing or thrashing is the process of loosening the edible part of grain from the straw to which it is attached. It is the step in grain preparation after reaping. Threshing does not remove the bran from the grain.

A line shaft is a power-driven rotating shaft for power transmission that was used extensively from the Industrial Revolution until the early 20th century. Prior to the widespread use of electric motors small enough to be connected directly to each piece of machinery, line shafting was used to distribute power from a large central power source to machinery throughout a workshop or an industrial complex. The central power source could be a water wheel, turbine, windmill, animal power or a steam engine. Power was distributed from the shaft to the machinery by a system of belts, pulleys and gears known as millwork.

A horse mill is a mill, sometimes used in conjunction with a watermill or windmill, that uses a horse engine as the power source. Any milling process can be powered in this way, but the most frequent use of animal power in horse mills was for grinding grain and pumping water. Other animal engines for powering mills are powered by dogs, donkeys, oxen or camels. Treadwheels are engines powered by humans.

A steam tractor is a tractor powered by a steam engine which is used for pulling.

The Case Corporation was a manufacturer of agricultural machinery and construction equipment. Founded, in 1842, by Jerome Increase Case as the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company, it operated under that name for most of a century. For another 66 years it was the J. I. Case Company, and was often called simply Case. In the late 19th century, Case was one of America's largest builders of steam engines, producing self-propelled portable engines, traction engines and steam tractors. It was a major producer of threshing machines and other harvesting equipment. The company also produced various machinery for the U.S. military. In the 20th century, Case was among the ten largest builders of farm tractors for many years. In the 1950s its construction equipment line became its primary focus, with agricultural business second.

A portable engine is an engine, either a steam engine or an internal combustion engine, that sits in one place while operating, but is portable and thus can be easily moved from one work site to another. Mounted on wheels or skids, it is either towed to the work site or moves there via self-propulsion.

Gaar, Scott & Co., was an American threshing machine and steam traction engine builder founded in 1849 and based in Richmond, Indiana. The company built simple and compound engines in sizes from 10 to 50 horsepower. Farm machinery produced by the firm were advertised as part of "the Tiger Line" and used a tiger upon two globes as the company logo. In the Fall of 1869, A. Gaar & Co. won "Best Portable Farm Steam Engine" and "Best Eight Horse Power" at the 17th Illinois State Fair, for which it won two Silver Medal prizes. It merged with the M. Rumley Co. in 1911 during a purchasing frenzy that put the later firm into insolvency. The company was reorganized as Advance-Rumely Thresher Company Inc. Advance-Rumely Thresher Company was later purchased by Allis-Chalmers Mfg. Co.

A jackshaft, also called a countershaft, is a common mechanical design component used to transfer or synchronize rotational force in a machine. A jackshaft is often just a short stub with supporting bearings on the ends and two pulleys, gears, or cranks attached to it. In general, a jackshaft is any shaft that is used as an intermediary transmitting power from a driving shaft to a driven shaft.

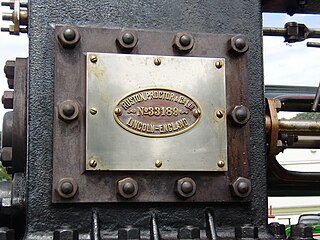

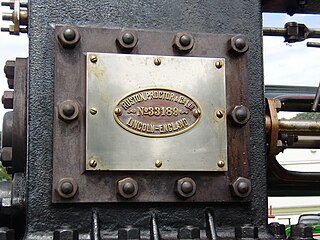

Ruston, Proctor and Company was established in Lincoln, England in 1857, and were manufacturers of steam tractors and engines. They later became Rustons and then Ruston & Hornsby.

Agricultural machinery relates to the mechanical structures and devices used in farming or other agriculture. There are many types of such equipment, from hand tools and power tools to tractors and the farm implements that they tow or operate. Machinery is used in both organic and nonorganic farming. Especially since the advent of mechanised agriculture, agricultural machinery is an indispensable part of how the world is fed.

A gin gang, wheelhouse, roundhouse or horse-engine house is a structure built to enclose a horse engine, usually circular but sometimes square or octagonal, attached to a threshing barn. Most were built in England in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The threshing barn held a small threshing machine which was connected to the gin gang via wooden gears, drive shafts and drive belt, and was powered by a horse which walked round and round inside the gin gang.

The agricultural machinery industry or agricultural engineering industry is the part of the industry, that produces and maintain tractors, agricultural machinery and agricultural implements used in farming or other agriculture. This branch is considered to be part of the machinery industry.

A living van is a portable caravan for temporary use of traveling work crews, especially of early steam engines. Living vans developed from the earlier shepherd's wagons, used to provide portable accommodation following a flock as they were moved between pastures.

A rope drive is a form of belt drive, used for mechanical power transmission.