Plant hormones are signal molecules, produced within plants, that occur in extremely low concentrations. Plant hormones control all aspects of plant growth and development, including embryogenesis, the regulation of organ size, pathogen defense, stress tolerance and reproductive development. Unlike in animals each plant cell is capable of producing hormones. Went and Thimann coined the term "phytohormone" and used it in the title of their 1937 book.

Auxins are a class of plant hormones with some morphogen-like characteristics. Auxins play a cardinal role in coordination of many growth and behavioral processes in plant life cycles and are essential for plant body development. The Dutch biologist Frits Warmolt Went first described auxins and their role in plant growth in the 1920s. Kenneth V. Thimann became the first to isolate one of these phytohormones and to determine its chemical structure as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). Went and Thimann co-authored a book on plant hormones, Phytohormones, in 1937.

In plant biology, thigmotropism is a directional growth movement which occurs as a mechanosensory response to a touch stimulus. Thigmotropism is typically found in twining plants and tendrils, however plant biologists have also found thigmotropic responses in flowering plants and fungi. This behavior occurs due to unilateral growth inhibition. That is, the growth rate on the side of the stem which is being touched is slower than on the side opposite the touch. The resultant growth pattern is to attach and sometimes curl around the object which is touching the plant. However, flowering plants have also been observed to move or grow their sex organs toward a pollinator that lands on the flower, as in Portulaca grandiflora.

Gravitropism is a coordinated process of differential growth by a plant in response to gravity pulling on it. It also occurs in fungi. Gravity can be either "artificial gravity" or natural gravity. It is a general feature of all higher and many lower plants as well as other organisms. Charles Darwin was one of the first to scientifically document that roots show positive gravitropism and stems show negative gravitropism. That is, roots grow in the direction of gravitational pull and stems grow in the opposite direction. This behavior can be easily demonstrated with any potted plant. When laid onto its side, the growing parts of the stem begin to display negative gravitropism, growing upwards. Herbaceous (non-woody) stems are capable of a degree of actual bending, but most of the redirected movement occurs as a consequence of root or stem growth outside. The mechanism is based on the Cholodny–Went model which was proposed in 1927, and has since been modified. Although the model has been criticized and continues to be refined, it has largely stood the test of time.

Thermotropism or thermotropic movement is the movement of an organism or a part of an organism in response to heat or changes from the environment's temperature. A common example is the curling of Rhododendron leaves in response to cold temperatures. Mimosa pudica also show thermotropism by the collapsing of leaf petioles leading to the folding of leaflets, when temperature drops.

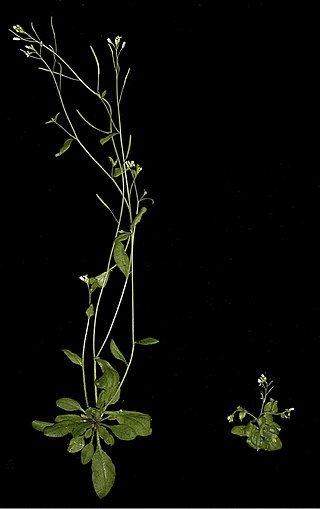

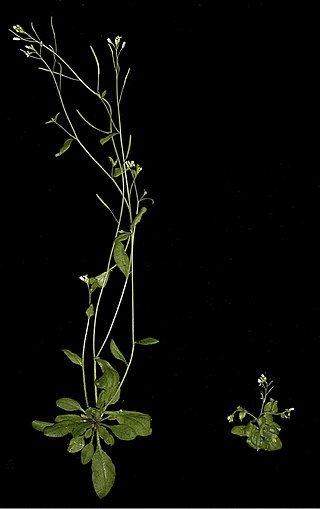

Shade avoidance is a set of responses that plants display when they are subjected to the shade of another plant. It often includes elongation, altered flowering time, increased apical dominance and altered partitioning of resources. This set of responses is collectively called the shade-avoidance syndrome (SAS).

Abscission is the shedding of various parts of an organism, such as a plant dropping a leaf, fruit, flower, or seed. In zoology, abscission is the intentional shedding of a body part, such as the shedding of a claw, husk, or the autotomy of a tail to evade a predator. In mycology, it is the liberation of a fungal spore. In cell biology, abscission refers to the separation of two daughter cells at the completion of cytokinesis.

In biology, nastic movements are non-directional responses to stimuli that occur more rapidly than tropisms and are usually associated with plants. The movement can be due to changes in turgor. Decrease in turgor pressure causes shrinkage, while increase in turgor pressure brings about swelling. Nastic movements differ from tropic movements in that the direction of tropic responses depends on the direction of the stimulus, whereas the direction of nastic movements is independent of the stimulus's position. The tropic movement is growth movement but nastic movement may or may not be growth movement. The rate or frequency of these responses increases as intensity of the stimulus increases. An example of such a response is the opening and closing of flowers, movement of euglena, chlamydomonas towards the source of light. They are named with the suffix "-nasty" and have prefixes that depend on the stimuli:

In botany, the petiole is the stalk that attaches the leaf blade to the stem. It is able to twist the leaf to face the sun, producing a characteristic foliage arrangement, and also optimizing its exposure to sunlight. Outgrowths appearing on each side of the petiole in some species are called stipules. The terms petiolate and apetiolate are applied respectively to leaves with and without petioles.

Alternaria alternata is a fungus causing leaf spots, rots, and blights on many plant parts, and other diseases. It is an opportunistic pathogen on over 380 host species of plant.

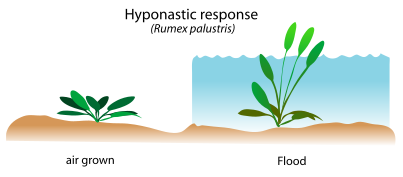

Rumex palustris, or marsh dock, is a plant species of the genus Rumex, found in Europe. The species is a dicot belonging to the family Polygonaceae. The species epithet palustris is Latin for "of the marsh" which indicates its common habitat.

Apetala 2(AP2) is a gene and a member of a large family of transcription factors, the AP2/EREBP family. In Arabidopsis thaliana AP2 plays a role in the ABC model of flower development. It was originally thought that this family of proteins was plant-specific; however, recent studies have shown that apicomplexans, including the causative agent of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum encode a related set of transcription factors, called the ApiAP2 family.

A pulvinus may refer to a joint-like thickening at the base of a plant leaf or leaflet that facilitates growth-independent movement. Pulvinus is also a botanical term for the persistent peg-like bases of the leaves in the coniferous genera Picea and Tsuga. Pulvinar movement is common, for example, in members of the bean family Fabaceae (Leguminosae) and the prayer plant family Marantaceae.

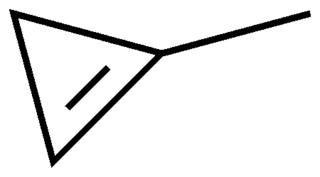

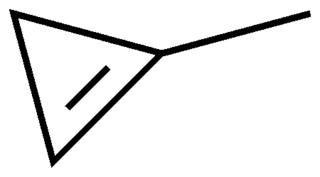

1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) is a cyclopropene derivative used as a synthetic plant growth regulator. It is structurally related to the natural plant hormone ethylene and it is used commercially to slow down the ripening of fruit and to help maintain the freshness of cut flowers.

A leaf is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, flower, and fruit collectively form the shoot system. In most leaves, the primary photosynthetic tissue is the palisade mesophyll and is located on the upper side of the blade or lamina of the leaf, but in some species, including the mature foliage of Eucalyptus, palisade mesophyll is present on both sides and the leaves are said to be isobilateral. Most leaves are flattened and have distinct upper (adaxial) and lower (abaxial) surfaces that differ in color, hairiness, the number of stomata, the amount and structure of epicuticular wax, and other features. Leaves are mostly green in color due to the presence of a compound called chlorophyll which is essential for photosynthesis as it absorbs light energy from the Sun. A leaf with lighter-colored or white patches or edges is called a variegated leaf.

In botany, the Cholodny–Went model, proposed in 1927, is an early model describing tropism in emerging shoots of monocotyledons, including the tendencies for the shoot to grow towards the light (phototropism) and the roots to grow downward (gravitropism). In both cases the directional growth is considered to be due to asymmetrical distribution of auxin, a plant growth hormone. Although the model has been criticized and continues to be refined, it has largely stood the test of time.

Bacterial blight of cotton is a disease affecting the cotton plant resulting from infection by Xanthomonas axonopodis pathovar malvacearum (Xcm) a Gram negative, motile rod-shaped, non spore-forming bacterium with a single polar flagellum

Gaseous signaling molecules are gaseous molecules that are either synthesized internally (endogenously) in the organism, tissue or cell or are received by the organism, tissue or cell from outside and that are used to transmit chemical signals which induce certain physiological or biochemical changes in the organism, tissue or cell. The term is applied to, for example, oxygen, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrous oxide, hydrogen cyanide, ammonia, methane, hydrogen, ethylene, etc.

Leaf expansion is a process by which plants make efficient use of the space around them by causing their leaves to enlarge, or wither. This process enables a plant to maximize its own biomass, whether it be due to increased surface area; which enables more sunlight to be absorbed by chloroplasts, driving the rate of photosynthesis upward, or it enables more stomata to be created on the leaf surface, allowing the plant to increase its carbon dioxide intake.

Ethylene (CH

2=CH

2) is an unsaturated hydrocarbon gas (alkene) acting as a naturally occurring plant hormone. It is the simplest alkene gas and is the first gas known to act as a hormone. It acts at trace levels throughout the life of the plant by stimulating or regulating the ripening of fruit, the opening of flowers, the abscission (or shedding) of leaves and, in aquatic and semi-aquatic species, promoting the 'escape' from submergence by means of rapid elongation of stems or leaves. This escape response is particularly important in rice farming. Commercial fruit-ripening rooms use "catalytic generators" to make ethylene gas from a liquid supply of ethanol. Typically, a gassing level of 500 to 2,000 ppm is used, for 24 to 48 hours. Care must be taken to control carbon dioxide levels in ripening rooms when gassing, as high temperature ripening (20 °C; 68 °F) has been seen to produce CO2 levels of 10% in 24 hours.