Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more parties to resolve points of difference, gain an advantage for an individual or collective, or craft outcomes to satisfy various interests. The parties aspire to agree on matters of mutual interest. The agreement can be beneficial for all or some of the parties involved. The negotiators should establish their own needs and wants while also seeking to understand the wants and needs of others involved to increase their chances of closing deals, avoiding conflicts, forming relationships with other parties, or maximizing mutual gains. Distributive negotiations, or compromises, are conducted by putting forward a position and making concessions to achieve an agreement. The degree to which the negotiating parties trust each other to implement the negotiated solution is a major factor in determining the success of a negotiation.

According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology, a feeling is "a self-contained phenomenal experience"; and feelings are "subjective, evaluative, and independent of the sensations, thoughts, or images evoking them". The term feeling is closely related to, but not the same as, emotion. Feeling may for instance refer to the conscious subjective experience of emotions. The study of subjective experiences is called phenomenology. Psychotherapy generally involves a therapist helping a client understand, articulate, and learn to effectively regulate the client's own feelings, and ultimately to take responsibility for the client's experience of the world. Feelings are sometimes held to be characteristic of embodied consciousness.

In psychology, a mood is an affective state. In contrast to emotions or feelings, moods are less specific, less intense and less likely to be provoked or instantiated by a particular stimulus or event. Moods are typically described as having either a positive or negative valence. In other words, people usually talk about being in a good mood or a bad mood. There are many different factors that influence mood, and these can lead to positive or negative effects on mood.

Appeal to emotion or argumentum ad passiones is an informal fallacy characterized by the manipulation of the recipient's emotions in order to win an argument, especially in the absence of factual evidence. This kind of appeal to emotion is irrelevant to or distracting from the facts of the argument and encompasses several logical fallacies, including appeal to consequences, appeal to fear, appeal to flattery, appeal to pity, appeal to ridicule, appeal to spite, and wishful thinking.

A rumor, or rumour, is "a tall tale of explanations of events circulating from person to person and pertaining to an object, event, or issue in public concern."

Nonverbal communication is the transmission of messages or signals through a nonverbal platform such as eye contact (oculesics), body language (kinesics), social distance (proxemics), touch (haptics), voice (paralanguage), physical environments/appearance, and use of objects. When communicating, we utilize nonverbal channels as means to convey different messages or signals, whereas others can interpret these message. The study of nonverbal communication started in 1872 with the publication of The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals by Charles Darwin. Darwin began to study nonverbal communication as he noticed the interactions between animals such as lions, tigers, dogs etc. and realized they also communicated by gestures and expressions. For the first time, nonverbal communication was studied and its relevance questioned. Today, scholars argue that nonverbal communication can convey more meaning than verbal communication.

Nonviolent Communication (NVC) is an approach to enhanced communication, understanding, and connection based on the principles of nonviolence and humanistic psychology. It is not an attempt to end disagreements, but rather a way that aims to increase empathy and understanding to improve the overall quality of life. It seeks empathic dialogue and understanding among all parties. Nonviolent Communication evolved from concepts used in person-centered therapy, and was developed by clinical psychologist Marshall Rosenberg beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. There are a large number of workshops and clinical materials about NVC, including Rosenberg's book Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. Marshall Rosenberg also taught NVC in a number of video lectures available online; the workshop recorded in San Francisco is the most well-known.

Assertiveness is the quality of being self-assured and confident without being aggressive to defend a right point of view or a relevant statement. In the field of psychology and psychotherapy, it is a skill that can be learned and a mode of communication. Dorland's Medical Dictionary defines assertiveness as:

In colloquial usage, contempt usually refers to either the act of despising, or having a general lack of respect for something. This set of emotions generally produces maladaptive behaviour. Other authors define contempt as a negative emotion rather than the constellation of mentality and feelings that produce an attitude. Paul Ekman categorises contempt as the seventh basic emotion, along with anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise. Robert C. Solomon places contempt on the same emotional continuum as resentment and anger, and he argues that the differences between the three are that resentment is anger directed towards a higher-status individual; anger is directed towards an equal-status individual; and contempt is anger directed towards a lower-status individual.

Couples therapy attempts to improve romantic relationships and resolve interpersonal conflicts.

Resentment is a complex, multilayered emotion that has been described as a mixture of disappointment, disgust and anger. Other psychologists consider it a mood or as a secondary emotion that can be elicited in the face of insult or injury.

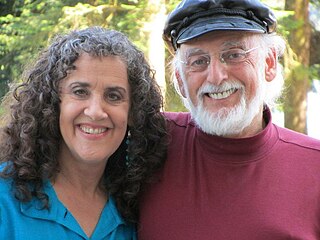

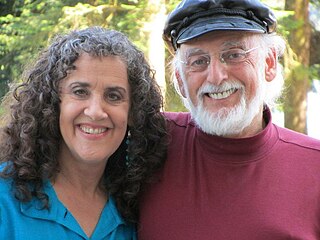

John Mordecai Gottman is an American psychologist and professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Washington. His research focuses on divorce prediction and marital stability through relationship analyses. Insights from Gottman's work have significantly impacted the field of relationship counseling, aiming to enhance relationship functioning and mitigate behaviors detrimental to human relationships. Gottman's work has also influenced the development of important concepts on social sequence analysis.

Parent Effectiveness Training (P.E.T.) is a parent education program based on the Gordon Model by Thomas Gordon. Gordon taught the first P.E.T. course in 1962 and the courses proved to be so popular with parents that he began training instructors throughout the United States to teach it in their communities. Over the next several years, the course spread to all 50 states. On November 1, 1970, Gordon wrote the Parent Effectiveness Training (P.E.T.) book. It became a best-seller and was updated in 2000 revised book.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to thought (thinking):

Appraisal theory is the theory in psychology that emotions are extracted from our evaluations of events that cause specific reactions in different people. Essentially, our appraisal of a situation causes an emotional, or affective, response that is going to be based on that appraisal. An example of this is going on a first date. If the date is perceived as positive, one might feel happiness, joy, giddiness, excitement, and/or anticipation, because they have appraised this event as one that could have positive long-term effects, i.e. starting a new relationship, engagement, or even marriage. On the other hand, if the date is perceived negatively, then our emotions, as a result, might include dejection, sadness, emptiness, or fear. Reasoning and understanding of one's emotional reaction becomes important for future appraisals as well. The important aspect of the appraisal theory is that it accounts for individual variability in emotional reactions to the same event.

The sociology of emotions applies sociological theorems and techniques to the study of human emotions. As sociology emerged primarily as a reaction to the negative effects of modernity, many normative theories deal in some sense with emotion without forming a part of any specific subdiscipline: Karl Marx described capitalism as detrimental to personal 'species-being', Georg Simmel wrote of the deindividualizing tendencies of 'the metropolis', and Max Weber's work dealt with the rationalizing effect of modernity in general.

Communicative behaviors are psychological constructs that influence individual differences in expressing feelings, needs, and thoughts as a substitute for more direct and open communication. More specifically, communicative behaviors refer to people's tendency to express themselves using indirect messages. Much of our communication is, in fact, non-verbal.

Emotions in the workplace play a large role in how an entire organization communicates within itself and to the outside world. "Events at work have real emotional impact on participants. The consequences of emotional states in the workplace, both behaviors and attitudes, have substantial significance for individuals, groups, and society". "Positive emotions in the workplace help employees obtain favorable outcomes including achievement, job enrichment and higher quality social context". "Negative emotions, such as fear, anger, stress, hostility, sadness, and guilt, however increase the predictability of workplace deviance,", and how the outside world views the organization.

Relational transgressions occur when people violate implicit or explicit relational rules. These transgressions include a wide variety of behaviors. The boundaries of relational transgressions are permeable. Betrayal for example, is often used as a synonym for a relational transgression. In some instances, betrayal can be defined as a rule violation that is traumatic to a relationship, and in other instances as destructive conflict or reference to infidelity.

Therapy speak is the incorrect use of jargon from psychology, especially jargon related to psychotherapy and mental health. It tends to be linguistically prescriptive and formal in tone.