History

| Part of a series on |

| Igbo people |

|---|

|

| Subgroups |

| Igbo culture |

| Diaspora |

| Languages and dialects |

| Politics (History) |

| Geography |

Originating primarily from what was known as the Bight of Biafra on the West African coast, Igbo people were trafficked in relatively high numbers to Jamaica as a result of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, beginning around 1750. The primary ports from which the majority of these enslaved people were taken from were Bonny and Calabar, two port towns that are now in south-eastern Nigeria. [4] The slave ships arriving from Bristol and Liverpool trafficked enslaved people to the British colonies including Jamaica. The bulk of enslaved Igbo people arrived relatively late, between 1790 and 1807, when the British passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act which outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire. Igbo people were spread on plantations on the island's northwestern side, specifically the areas around Montego Bay and St. Ann's Bay, [5] and consequently, their influence was concentrated there. The region also witnessed a number of revolts that were attributed to people of Igbo origin. Slave owner Matthew Lewis spent time in Jamaica between 1815 and 1817 and studied the way enslaved people he claimed ownership of organised themselves by ethnicity and he noted, for example, that at one time when he "went down to the negro-houses to hear the whole body of Eboes lodge a complaint against one of the book-keepers". [6]

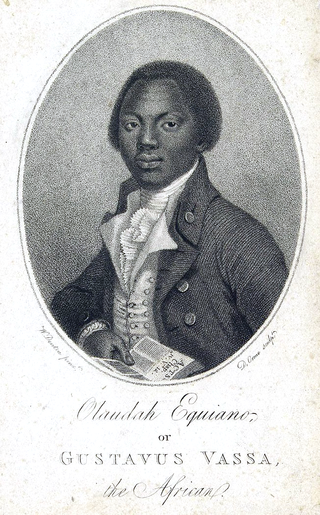

Olaudah Equiano, a prominent member of the movement for the abolition of the slave trade, was an African-born Igbo formerly enslaved person. On one of his journeys to the Americas as a free man, as documented in his 1789 journal, Equiano was hired by Dr. Charles Irving to recruit enslaved people for his 1776 Mosquito Shore scheme in Jamaica, for which Equiano hired enslaved Igbo, whom he called "My own countrymen". Equiano was especially useful to Irving for his knowledge of the Igbo language, using Equiano as a tool to maintain social order among his enslaved Igbo in Jamaica. [7]

Enslaved Igbo were known, many a times, to have resorted to resistance rather than revolt and maintained "unwritten rules of the plantation" of which the plantation owners were forced to abide by. [8] Igbo culture influenced Jamaican spirituality with the introduction of Obeah folk magic; accounts of enslaved "Eboe" being "obeahed" by each other have been documented by plantation owners. [6] However, there is some suggestion that the word "Obeah" was also used by enslaved Akan people, before Igbos arrived in Jamaica. [9] Other Igbo cultural influences include the Jonkonnu festivals, Igbo words such as "unu", "una", idioms, and proverbs in Jamaican patois. In Maroon music were songs derived from specific African ethnic groups, among these were songs called "Ibo" that had a distinct style. [10] Igbo people were hardly reported to have been Maroons.

Enslaved Igbo people were known to have committed mass suicides, not only for rebellion, but in the belief their spirits will return to their motherland. [4] [11] In a publication of a 1791 issue of Massachusetts Magazine , an anti-slavery poem was published called Monimba, which depicted a fictional pregnant enslaved Igbo woman who committed suicide on a slave ship bound for Jamaica. The poem is an example of the stereotype of enslaved Igbo people in the Americas. [12] [13] Enslaved Igbo were also distinguished physically by a prevalence of "yellowish" skin tones prompting the colloquialisms "red eboe" used to describe people with light skin tones and African features. [14] Enslaved Igbo women were paired with enslaved Coromantee (Akan) men by slave owners so as to subdue the latter due to the belief that Igbo women were bound to their first-born sons' birthplace. [15]

Archibald Monteith, whose birth name was Aniaso, was an enslaved Igbo man taken to Jamaica after being tricked by an African slave trader. Anaeso wrote a journal about his life, from when he was kidnapped from Igboland to when he became a Christian convert. [16]

After the abolition of slavery in Jamaica in the 1830s, Igbo people also arrived on the island as indentured servants between the years of 1840 and 1864 along with a majority Kongo and "Nago" (Yoruba) people. [17] Since the 19th century most of the population African Jamaicans had assimilated into the wider Jamaican society.[ citation needed ]

Rebellions and uprisings of enslaved people

Enslaved Igbo people, along with "Angolas" and "Congoes" were often runaways, liberating themselves from enslavement. In slave runaway advertisements held in Jamaica workhouses in 1803 out of 1046 Africans recorded, 284 were described as "Eboes and Mocoes", 185 "Congoes", 259 "Angolas", 101 "Mandingoes", 70 Coromantees, 60 "Chamba" of Sierra Leone, 57 "Nagoes and Pawpaws" and 30 "scattering". 187 were documentined as "unclassified" and 488 were "American born negroes and mulattoes". [18]

Some notable rebellions of enslaved people involving Igbo include:

- The 1815 Igbo conspiracy in Jamaica's Saint Elizabeth Parish, which involved around 250 enslaved Igbo people, [19] described as one of the revolts that contributed to a climate for abolition. [20] A letter by the Governor of Manchester Parish to Bathurst on April 13, 1816, [21] quoted the leaders of the rebellion on trial as saying "that 'he had all the Eboes in his hand', meaning to insinuate that all the Negroes from that Country were under his control. [22] The plot was thwarted and several enslaved people were executed.

- The 1816 Black River rebellion plot, was according to Lewis (1834:227—28), carried out by only people of "Eboe" origin. [23] This plot was uncovered on March 22, 1816, by a novelist and absentee planter named Matthew Gregory "Monk" Lewis. Lewis recorded what Hayward (1985) called a proto-Calypso revolutionary hymn, sung by a group of enslaved Igbo, led by the "King of the Eboes". They sang:

Oh me Good friend, Mr. Wilberforce, make we free!

God Almighty thank ye! God Almighty thank ye!

God Almighty, make we free!

Buckra in this country no make we free:

What Negro for to do? What Negro for to do?

Take force by force! Take force by force! [24]

- "Mr. Wilberforce" was in reference to William Wilberforce a British politician who was a leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. "Buckra" was a term introduced by enslaved Igbo and Efik people in Jamaica to refer to white slave owners and overseers. [25]